Obituary: Billy Graham

- Published

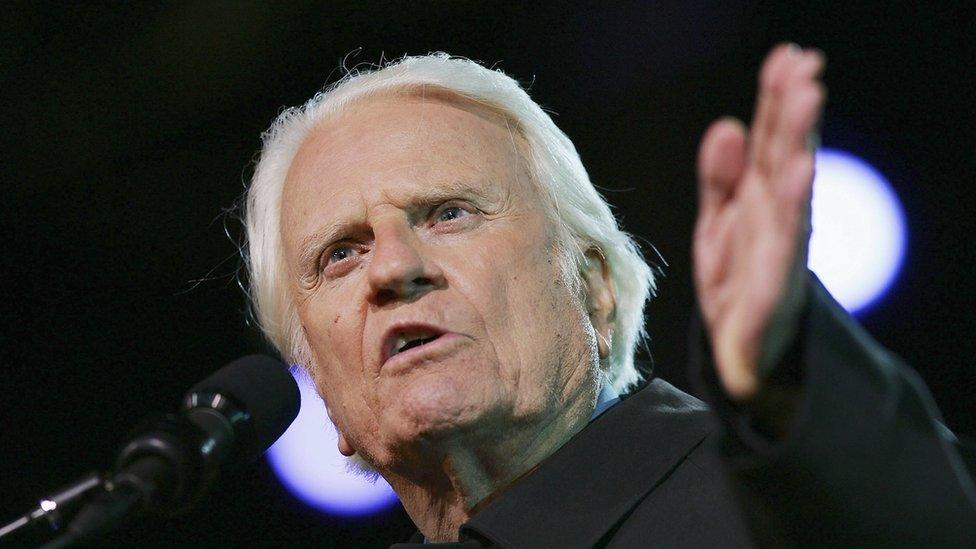

He continued spreading his message well into his 80s

Once dubbed God's Ambassador, Billy Graham went to the four corners of the world with his evangelical mission.

His soft-spoken Southern style was in direct contrast to the fire and brimstone adopted by so many evangelical preachers.

Over six decades, he preached to an estimated 215 million people in 185 countries and reached hundreds of millions more through his radio and television ministry.

His early audiences were predominantly white, middle-class and conservative.

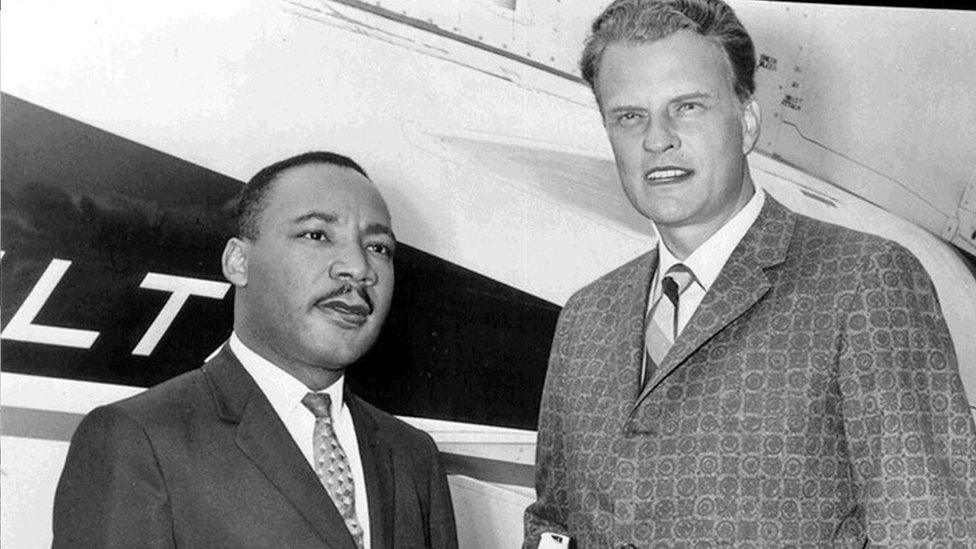

But, as the civil rights movement gained momentum, he began to preach against segregation and formed a sometimes strained friendship with Martin Luther King.

William Franklin Graham Jr was born on 7 November 1918 and brought up on the family dairy farm in Charlotte, North Carolina.

His parents were members of the conservative Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church.

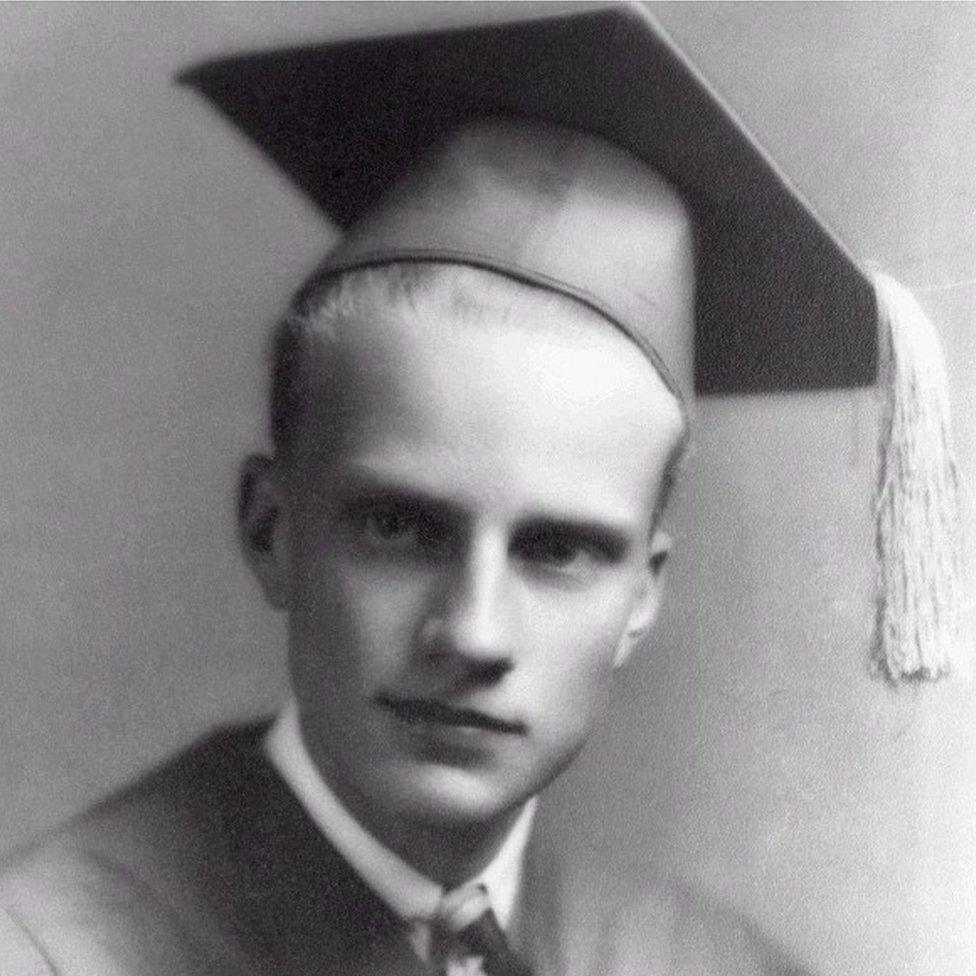

By the time this graduation picture was taken he had found his calling

When Prohibition ended in 1933, his father forced him to drink beer until he was sick to persuade him of the dangers of alcohol. He remained a teetotaller throughout his life.

He made a commitment to Christ when he was 16 after hearing Mordecai Ham, a travelling evangelist, and he was ordained a minister in 1939.

His plan to serve as an army chaplain during World War Two ended when he contracted mumps. Instead he studied at the Florida Bible Institute and in 1943, married Ruth McCue Bell.

He became a full-time evangelist with Youth for Christ, an organisation that ministered to young people and service personnel.

Segregation

The man who had worked as a travelling salesman during the Depression had emerged as one of the great promoters of the Christian religion.

In 1949 he came to wider public attention when he preached for eight weeks in a giant tent in Los Angeles, which gained the nickname the Canvas Cathedral.

The growing civil rights movement forced Graham to confront the racism inherent in US society.

Graham (l) in the Canvas Cathedral with his music director Cliff Barrows

At first he was ambivalent about the need for change and often, in the early 1950s, preached to segregated audiences .

However, a court ruling that segregation in American schools was unconstitutional saw Graham insist on integrated seating at all his meetings.

He was an outspoken opponent of communism, believing that it had "decided against God, against Christ, against the Bible, and against all religion".

After the success of his ministry in the US, Graham wanted to take his message worldwide and he began the process in London in 1954.

Demand

It was a calculated risk. At the time only 10% of Britons were regular churchgoers, compared with 50% in the United States.

He also faced a hostile British press, which was scathing about the motives of the man from Charlotte, and he faced calls from one MP for him to be banned from entering the UK.

He conducted his first full-scale mission in a 12,000-seat auditorium next to a greyhound track at London's Harringay Arena.

Thousands flocked to hear him preach in London in 1954

Such was the demand to hear him that he filled the arena every night for three months.

The final meeting of his UK crusade was held at Wembley Stadium, when 120,000 people heard Graham speak of the reception he had received in London.

"These meetings have been far beyond anything we had the faith to believe possible," he told the crowd. "The spirit of God is moving across Great Britain as perhaps at no time in the last century."

It was the beginning of what would be a series of missions to all parts of the globe.

Regal treatment

His crusades were always meticulously planned. As his reputation grew, so too did the crowds, from New York to Nigeria. In Korea, more than a million turned out to hear him speak.

In 1957 he invited the civil rights leader Martin Luther King to join him on a 16-week stint in New York, which more than two million people attended.

Graham's friendship with King was sometimes difficult, not least when he attacked King for his stand against the war in Vietnam, branding the civil rights leader as unpatriotic.

His relationship with Martin Luther King was not always cordial

But Graham was effusive in his tributes when King was assassinated in 1968, declaring that America had lost "a social leader and a prophet".

By the time that Graham headed back to Britain in 1966, he was receiving almost regal treatment.

During this mission, at a rally at Earl's Court, the singer and film star Cliff Richard made his public commitment to Christianity.

As the years went by, with controversy increasing over the techniques of mass evangelism, Billy Graham's delivery may have become more measured but the focus of all his rallies remained "the invitation".

People were encouraged to come to the stage and personally witness to their reborn faith.

And he was clear about the importance of personal contact with his vast congregation.

"I've had many opportunities to see what the average clergy would never see. And on each of those occasions I've tried to let those I've come in contact with see a little bit of what the Gospel of Jesus Christ is about."

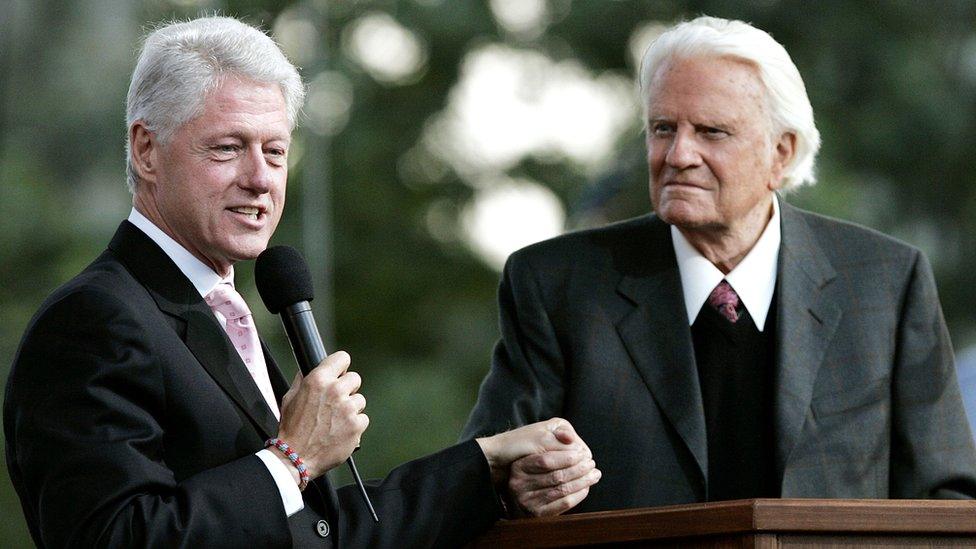

He was seen at the side of numerous US presidents, including Bill Clinton

In a mission that lasted 60 years, he preached in person to more people than anyone else.

Graham's final revival meeting took place in New York in June 2005. Acknowledging his own advanced age, then 86, he told the congregation: "I know it won't be long."

Though a Baptist himself, he encouraged converts to choose a church for themselves and worked for ecumenical unity.

He was to be seen at the side of each American president, though his endorsement of Richard Nixon did not hold him back from criticising the disgraced former leader over the Watergate scandal.

No scandal of any kind ever came to undermine Billy Graham's own ministry, unlike a number of other high-profile evangelists.

However, in 2002 he was forced to publicly apologise for remarks he had made about the "Jewish stranglehold on the media", which came to light when tapes of a private conversation with Richard Nixon in 1972 were released.

But it was his continuing missions, or crusades, that had the greatest impact. The charisma of Billy Graham's preaching and the success of his invitation to witness touched the lives of millions of people from all over the globe.

At the core of his message was the eternal optimism that everyone could find salvation through God.

"I've read the last page of the Bible," he once said. "It's all going to turn out all right."