How a red ribbon conquered the world

- Published

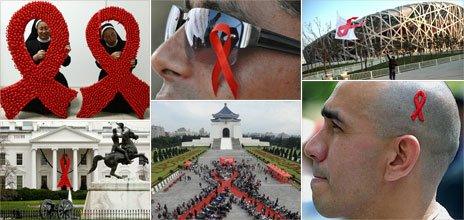

The red ribbon has become a global symbol

Thirty years after the HIV virus was first documented, the red ribbon is the ubiquitous symbol of support for those living with the illness. Who thought of it and how did it get so big?

In the sparse surroundings of a former classroom on a spring day in 1991 - a decade after the rise of Aids - a group of 12 artists gathered to discuss a new project.

They were photographers, painters, film makers and costume designers, and they sat around in the shared gallery space known as PS122 in New York's East Village.

Within an hour or so of brainstorming, they had come up with a simple idea that later became one of the most recognised symbols of the decade - the red ribbon, worn to signify support for people with HIV/Aids.

"We wanted to make something that was self-replicating," says Patrick O'Connell, who chaired the meeting. "It's extremely simple, like Bauhaus but half a century later. You cut the ribbon 6-7 inches, loop it around your finger and pin it on. You can do it yourself."

The ribbon was the latest project by Visual Aids, a New York arts organisation that raises awareness of HIV/Aids.

When they sat down in the shared gallery space of PS122 in May 1991, they wanted to get people talking about the illness that was decimating their professional and social network, in the face of public indifference and private shame.

People were dying without even telling their friends why they were sick, and the artists wanted a visual expression of compassion for people living with Aids and their carers.

At the start, Visual Aids volunteers made the ribbons themselves

"Even in New York, we were very aware of how many people couldn't talk about it, or were oblivious, or were going through it themselves but ashamed to talk about it," says photographer Allen Frame, who was also one of the 12. "We wanted to make people feeling isolated more supported and understood."

Their inspiration came from the yellow ribbons tied on trees to denote support for the US military fighting in the Gulf War, he says. Pink and the rainbow colours were rejected because they were too closely associated with the gay community, and this was an illness that went well beyond.

"Red was something bold and visible. It symbolised passion, a heart and love."

The shape had no significance but was easy to make.

It took two more meetings to refine the design and then they set to work on making the ribbons themselves, distributing them around the New York art scene and dropping them off at theatres.

Initially there was a text that went with it, to explain why they were being worn, although this was later dropped because it became superfluous.

A few weeks after that first meeting, the group sent a box of 3,000 ribbons to the Minskoff Theatre on Broadway, ahead of the Tony Awards for the theatre industry. Some of them were making ribbons and watching the televised event as actor Jeremy Irons, one of the presenters, came on to the stage wearing one.

"Within three days, the media finally figured it out and it snowballed. I started being contacted by people in Hollywood," says O'Connell.

Demand increased to such a degree that supply needed to be outsourced, and Visual Aids used a charity working with homeless women to make the ribbons. They sent out 10,000 ribbons for one Oscars ceremony, and over the coming years they made about 1.5m.

Liz Taylor frequently wore one, having lost friends to Aids

Stars like Bette Midler and Richard Gere were not only wearing them, but openly discussing why it was important. A ribbon-sporting culture developed within the acting profession.

"It became trendy and sometimes I think celebrities felt blackmailed and thought they had to show up wearing a ribbon, which wasn't the case," says O'Connell. "We weren't keeping count that way."

The ribbons first crossed the Atlantic in large numbers on Easter Monday in 1992, when more than 100,000 ribbons were distributed at an Aids benefit concert in London's Wembley Stadium for Freddie Mercury.

They also began to proliferate in mainstream American life. Schools and churches across the US touched by the illness started to contact Visual Aids for advice on how they could explain it to children and parishioners - the answer was to hold a ribbon-making event.

"This was a way to educate people in a non-combative way," says O'Connell, who has a ribbon on every item of clothing. Direct action was still important, he says - campaigners occupied the Stock Exchange and tried to re-enact a funeral on the White House lawn - but the ribbon was a way to broaden the conversation.

One unforeseen consequence has been the number of awareness ribbons, external that have been adopted since - pink for breast cancer being the most well known.

The artists purposefully never trademarked it - the point of the project was to invite more people in, says O'Connell - which meant it could appear anywhere without Visual Aids' permission or any payments. It even turned up on a US Post Office stamp.

But he and some of the other artists behind the concept believe the proliferation and merchandising of the ribbon - ornamental ribbons selling for $19.95 in department stores and red ribbon mugs - has commercialised and trivialised their idea.

In a spirit more in tune with the one envisaged by Visual Aids, the ribbon is replicated in many different forms for memorials on World Aids Day, and its symbolism no longer needs any explanation.

In the poorest parts of the world, ribbon production has been central to efforts to raise funds and change attitudes, says Sir Nick Partridge, chief executive of the Terrence Higgins Trust in the UK.

Women's collectives make ribbons and adorn them before selling them in their community.

"A number of people living with HIV really appreciate seeing other people wearing the red ribbon. They realise they're not alone and recognise that the majority of people wearing them probably don't have HIV themselves, and that sense of support and solidarity is very, very important.

"There has been some criticism, that it is only a symbol. But symbols are important, and the way in which the red ribbon was embraced by community activists, doctors and researchers is a unifying emblem in what is a very disparate epidemic.

"The brilliance of the artists was not copyrighting it. Making it freely available was a gift to the Aids community worldwide."

Those 12 artists never worked together again as a group, but with the battle against the illness ongoing, their activism continues.