9/11: The 73 minutes that changed my life

- Published

Like thousands of other New Yorkers, Artie Van Why saw the attacks on the World Trade Center from the streets below. What he witnessed in those minutes changed his life profoundly and will, he believes, continue to haunt him until the day he dies.

The moment he walked through the revolving doors of his office building and stepped on to the street on that sunny September morning, Artie Van Why's world shifted a few degrees on its axis.

His life from that instant took a different course, propelled by the mayhem that enveloped him that day, events the world later identified by two numbers, nine and 11.

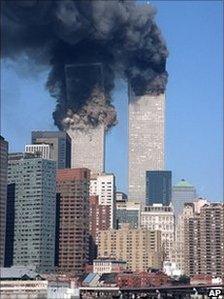

Millions of people watched on television as four hijacked planes crashed in the US, two of them into one famous New York landmark. But Van Why was in the thick of it.

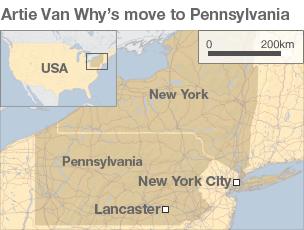

The experience forced him to leave New York, his home for 26 years, and move more than 100 miles west to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, deep in Amish country.

Download the tablet version

The 73 minutes that changed my life[655 KB]

Most computers will open PDF documents automatically, but you may need Adobe Reader

Ten years after the atrocities, sitting in the corner of a humble one-bedroom apartment located above a funeral home, his face is a picture of concentration as he recalls the day's events.

"I remember it was a beautiful day. Whenever I see a really beautiful blue sky, it takes me back to that morning."

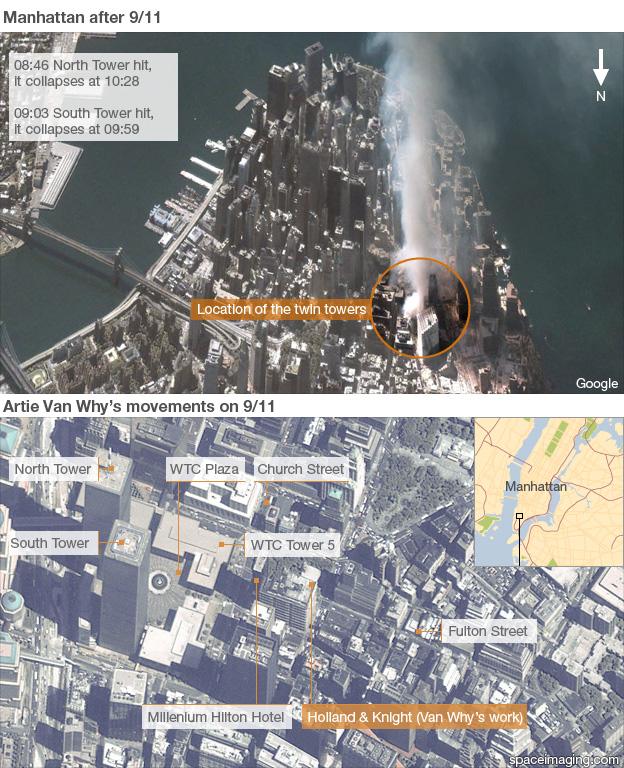

He was working as a clerical assistant at law firm Holland & Knight, and his office was on the 23rd floor of a building separated from the World Trade Center site only by Church Street and the Millennium Hilton hotel. At 08:46, a loud boom shook the building.

A colleague asked if it was thunder, then someone screamed for everyone to get out of the building, because a plane had hit one of the twin towers. Expecting to see a small aircraft sticking out of the famous skyscraper, Van Why took the lift to the ground floor and exited through a revolving door.

"It was like the Wizard of Oz, stepping into another world. It seemed as everything slowed down and it was going frame by frame as if in slow motion.

"All these white paper sheets were covering the ground like snow and coming down. I remember thinking that I'd never seen so much paper.

"I walked a short distance to Church Street where the towers were and that's when I saw the North Tower for the first time. I was dumbstruck. It was hard to comprehend what I was seeing.

"There was a huge black hole, the flames were bright orange and the smoke was billowing out of the tower."

More people were arriving on the streets, he says, and sirens could be heard in the background. As his recollections become more vivid, the 58-year-old closes his eyes and rocks back and forth in his orange armchair, his right foot tapping the carpet vigorously.

His rented apartment is full of reminders of what he went through. A photo of the World Trade Center is on the fridge, and other photographs featuring the famous Manhattan skyline adorn the living room, like pictures of a deceased member of the family.

Reminders of the life left behind fill his apartment

One wall is full of framed newspaper cuttings, reviews of the play that Van Why - a former actor - wrote and performed about 9/11. And in front of this shrine, he sits and recalls the minutes that reshaped his life, wild hand gestures making the scene all the more real.

"I don't know how long I was looking at the North Tower, trying to take it all in. I was transfixed. What broke it was when I realised there were other things falling, there were people falling and everyone realised at the same time.

"People started screaming and my reaction was to scream 'No, No, No!' at the thought that people were falling down. And that's when - I don't know why I reacted in this way - but my instinct was to run towards them.

"I ran to the plaza where they were falling. I didn't have a moment's thought, I just ran towards the tower, thinking 'Can I help these people?' I imagined them laying there and the thought of being able to hold their hand or sit and be with them, comfort them."

Another man was running with him, and for a moment, the two stopped and stood side by side, taking in the enormity of what they were seeing - human beings jumping to their deaths. Van Why recalls seeing bodies piling up on the ground.

"One of my most vivid memories is looking to my left and I saw this man in a suit falling. Somehow I had thought that if you ever jumped from a high place, you would be dead before you hit the ground.

"But I remember seeing how very much alive he was and I can still see his arms and legs moving as if to brace himself. Fortunately I didn't see him hit."

Some guards shouted for the two men to come to safety through another World Trade Center Building, number 5. They went down a lift and out of the site on to Church Street, from where Van Why saw the second plane hit the South Tower, only 17 minutes after the first.

Pandemonium broke out. Debris was raining down, he says, as he ran towards Fulton Street, at one point falling to the ground.

"People started to run over the top of me and I thought I was going to be trampled to death but I managed to get up. I remember shouting out 'God, save us all!'"

He recalls an African-American woman tripping and being helped to her feet by a businessman. Then he ran past a large man who was lying face down in the street.

Getting down on his knees, Van Why saw that the man had a serious head injury. He appeared to have been hit by a putty knife that had fallen from one of the buildings and was lying nearby stained with blood.

"Another man stopped and gave me a denim jacket which we put over the open wound and then I remember seeing his watch on the street beside him and I put it in his pants [trouser] pocket. We turned him over and he had a work tag with a name."

With tears falling and his voice cracking, Van Why goes on: "My biggest regret is that I didn't look to his tag to see what the name was. I could have found his family and told them that there were people with him."

An ambulance arrived and it required several people to lift the man on to the stretcher. Van Why stroked his arm and told him he would be fine.

Realising he had left his mobile phone in the office, he began asking strangers if he could borrow one to get the message through to his parents that he was OK. But none of the phones were working, so he went into a cafe and used a telephone there.

When he emerged, he heard a deafening sound. He looked to his left and saw a wall of grey smoke coming towards him. The South Tower was collapsing.

For the second time that morning, he started running. The time was 09:59, 73 minutes after the first plane flew into the North Tower.

By the time he got to his apartment on 43rd Street, after deliberately avoiding the area around the Empire State Building, it was approaching noon. The North Tower had also collapsed, but Van Why had been far enough away to not hear it.

In the days that followed, he slept only fitfully and always with the bedroom light on.

"I was afraid of the dark. It never happened before 9/11. It was a sense of security having that light on.

"For that first week I would wake up early and call my parents first thing. I would be on the phone crying with them. There was a lot of crying that week.

"I was feeling sadness and grief and mourning like I had never felt, similar to losing a loved one. And still an incomprehension, trying to understand what had happened."

He avoided watching television or reading newspapers because he could not bear to see replays or photos of the planes striking the towers. He had his own images, pictures inside his head, sometimes appearing with a clarity that transported him back to the mayhem.

He discovered that two men who lived in his apartment building were missing and a lawyer at work who was last seen running towards the towers was also presumed dead.

Van Why had done exactly the same and survived. As a recovering alcoholic who had been sober for two years, he already had a therapist, and in the weeks following 9/11 he saw him daily.

Alcoholics Anonymous meetings were also an opportunity to share his feelings with others, but he lived alone and had no partner to provide constant support. Before long he was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Holland & Knight opened makeshift offices at a hotel in Midtown but he did not feel able to go back to work until two or three weeks after the attacks. When he did, it was the first time he had ventured outside his neighbourhood.

A few days later, he rented a car and drove to Maryland, for a 30-year high school reunion. The sight of an aeroplane coming into land caused him to burst into tears. At the event, when he introduced himself by saying: "I'm from the greatest city in the world, New York City," people stood up and applauded.

His old offices near Ground Zero were soon ready again, but Van Why found returning to the scene too harrowing to endure. The smell of smoke from the still-smouldering site would fill his nostrils as he emerged from the subway.

The WTC plaza - once his lunchtime sanctuary - now resembled to him a grave. One morning, the police allowed him to enter the site so he could lay six roses on what he regarded as "hallowed ground".

In November 2001, he resigned from work after 13 years of service. It was too painful to continue. He instead focused on his new project - writing his own story about his experience.

He had written emails to family and friends following the attacks, to explain what happened, and they forwarded his story to other people. Soon he began to receive appreciative emails from strangers.

Encouraged, he began to develop his story into a script, convinced it was his mission to keep the memory alive. It became a one-man play that he performed off-Broadway and in Los Angeles.

"The play gave me a sense of purpose. Those two years after 9/11, when I was really focused on my play, that is the only time in my life I felt fulfilled, because I had a purpose and I thought I was doing something important and something selfless, because I was doing it for the memory of the people I saw die."

After each performance, some people would tell him their own story of where they were, making him realise, he says, that people across the US had a story of 9/11.

He was hoping he could continue performing the show for at least five years.

"I wanted to dedicate my life to it. But it closed in New York earlier than planned, the major papers ignored it and some reviews were critical, saying I was trying to profit out of it."

It seemed to him like the city was ready to move on and he was not. The spirit that defined New York in the days, weeks and months afterwards had gone, he says, and he felt a bit like a "lone crusader".

Van Why performed his play in 2003

"It still weighed so heavily on my emotions and who I was, so to see other people weren't doing that and moving on, it was like 'How can they be doing that?'

"There was anger and a feeling of isolation. In the month after 9/11, it was all you talked about with strangers, but two years afterwards, there was a sense that 'OK, you don't need to talk about this any more.'"

Immersing himself for years in writing and performing the play probably held him back, he admits, because he was dwelling on the events and re-living them, but not dealing with the emotions.

That process did not begin until he moved. In September 2003, he started a new life in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, because he wanted to be near his parents.

"I never thought I would leave New York, I envisaged my last days would be in New York but it just seemed like the right thing to do."

He felt guilty about leaving, but the pull of family was overwhelming and he felt like he had nowhere else to go.

"All of a sudden I just needed to be closer to them, I wanted it and needed it. For me and my parents, the reality that 9/11 was a day that I could have died brought the importance of being with my family to me.

"Though I was in my 50s, there was a sense that I needed mummy and daddy, that sense of security and that sense of home."

Growing up, home was Gaithersburg in Maryland, where the young Van Why was a quiet boy, according to his parents.

He says he felt different from other children - he later realised he was gay - and was bullied.

After high school, he attended a small, conservative Christian college, where he majored first in Bible studies, then in drama.

He moved to New York in 1977 with the dream of becoming an actor but after struggling for 10 years to get sustained work in the theatre, he gave it up. The clerical work that had been a supplement to his income became his main and only job.

As a young man, he'd had a difficult relationship with his parents and throughout his adult life he had seen them only three or four times a year. It was not until he moved to Pennsylvania, two years after the attacks, that his relationship with them, in his own words, "fully healed".

"I didn't know what it would entail, moving here, but eight years later, my relationship with my parents is incredible. It has a depth and appreciation it has never had before."

When he arrived in 2003, he didn't have a job, an apartment or a car, and he left many long-standing friendships behind in New York. And there was no-one who could relate to what he had been through.

After the bright lights of Manhattan, the small city of Lancaster - with fewer than 60,000 residents and a homespun, rural charm - struck a tranquil note.

Van Why withdrew socially, spending a lot of time in what he calls his "cave", a room where he would just watch television endlessly at weekends. Even when he was coaxed out of his isolation by colleagues for a coffee, he was lost and distracted.

A low period at the end of last year, when he was often breaking down, was his grief finally being released, he believes.

"I was very fortunate I did not lose my physical life but I lost my life as I knew it. The person I was on September 10th, that person is no longer. I had to go through a very emotional period which enabled me to go and face Ground Zero."

In the last few months he has started to come out of his metaphorical cave. The first step on the road to recovery was going back to New York in April, for the first time since he left in 2003. With his parents and sister Sue by his side, he visited the place that had haunted him for nearly a decade.

"That was a huge step for me. It was very emotional but it helped to put an end to that chapter of my life. Even though I had been away for eight years, there was guilt that I had left my city when it was still healing."

Only having closed that door, could he start to regard Lancaster as home, he says. Shortly after that trip, he met someone and began a relationship.

"Being with him, I realised that I had forgotten what it was like to be happy. It's like I am stepping back into life. I'm finally moving past mourning."

But there are other struggles. He has two jobs, one in the box office of the Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, and another as a cashier in a Weis supermarket. The two incomes combined earn him about $20,000 (£12,196) a year, about $50,000 (£30,494) less than he was earning in New York.

It's a thorn in his side, he says. "I have debts and try to pay them off when I can and meet my basic expenses. So far, I've been lucky to just get by."

If he had been told in 2001 that in 10 years he would be living in Pennsylvania and working in a theatre and a supermarket, he would have been shocked.

"I liked my job. I liked working down there. And, yes, I was making a good salary. I would like to think I might have developed a relationship with someone.

"At the time of 9/11, I was in the best place I had been for a long time - sober and happy. Perhaps I would have been able to take vacations and travel, things I'm unable to do now."

And the images are still there every day, sometimes popping into his head without warning, with such force that he zones out while his mind revisits the carnage.

"They are like snippets of a movie. I will replay watching this one man who I saw falling, watching him. I will flash to the injured man I saw laying in the streets. It's a series of vignettes that my mind just goes back to."

A siren is enough to take him back there and it's a sound that makes his body tighten. He still has not boarded a plane, although tall buildings don't instil in him the same fear they once did.

A study by Cornell University suggests that the trauma suffered by witnesses like Van Why may have physically altered their brains, damaging their ability to process emotions.

He says 9/11 survivors and witnesses like himself are the "forgotten majority", never considered among the victims.

"They're not letting any survivors to the [10th anniversary] ceremony in New York, it's just bereaved family members.

"There's a sense that you don't count. Some people are still struggling terribly, far worse than I am. Everyone who was there is still affected to a degree, but people don't remember us.

"We're not suffering physically and weren't injured that day and didn't lose a family member. It's like we don't count."

Despite the financial and mental strains, he is now looking to the future with a new optimism.

"It's my life now and I've never accepted that before. That's another change in the past months. Not that I was fighting it before, but there's an acceptance, I'm moving out of the mourning stage and back to life again."

It's comparable to losing a partner, he says, with the memory of that loved one never disappearing but gradually losing its hold.

"I can't imagine a day going by when I don't think about it, even as a passing thought.

"What I was doing for a long time was letting 9/11 define who I was and I think I'm getting away from that now. My experience of 9/11 is part of who I am but not all of me."

Photographs by Adam Blenford