Is torture ever right?

- Published

- comments

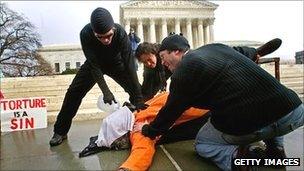

Demonstrations against torture have taken place across the US during the past several years

It is nearly 10 years since the 9/11 attacks, a horrific day that changed the world as well as America.

In a country with a reverence for its constitution, debates about practical questions often end up as arguments about first principles.

The attacks on America prompted fierce battles about how civilised societies should treat their enemies, and whether torture can ever be right.

I've been asking a top CIA officer how he felt about what was happening at black sites and Guantanamo Bay prison. Phil Mudd, external was deputy director of the Office of Terrorism Analysis at the CIA in 2001.

"I remember so many times, sitting at the nightly, what we'd call 'the five o'clock', the threat briefing for (CIA) director Tenant," he says.

Defining torture

"And you would sit there on a Friday night, it'd be seven o'clock, you're going to miss dinner again, miss going out with your friends, realising: okay, let's say, we've got a new prisoner. I don't know what's going to happen tomorrow, but we need to know quickly, we need to know."

He adds: "Maybe another child will die, maybe more parents will die. The sense of immediacy was balanced against what we knew were sensitive techniques that would come to light some day. Nobody had any illusions in the system that this would stay secret forever."

It didn't.

What came to light was an extraordinary memo, external from the US justice department arguing that while torture would be illegal under American law, inflicting pain in order to get information wasn't torture.

It says "certain acts may be cruel, inhumane or degrading but still not produce pain of the requisite intensity" to be called torture.

"The pain had to be extreme, equivalent to serious physical injury or organ failure," the memo goes on to say.

Mr Mudd was nominated to be President Obama's undersecretary of intelligence, external, but dropped out because of what he knew about interrogation techniques under the previous administration.

He did know what was going on.

Mr Mudd says: "Nothing justifies torture. That's it. Nothing. There are questions about whether it's appropriate for example to push someone against a flexible wall, if that saves a child's life.

"How about this - if you push someone against a wall, and all of a sudden they don't know what's going to happen, they get nervous and they say: 'I'll talk to you about a plot.' Is that fair? Is that legitimate? Is that torture?

"Technically, that would be torture, in some cases, because that's physical aggression against a prisoner," Mr Mudd says.

"In our case, we asked the Department of Justice, and they said that's perfectly legitimate under the constitution. Our goal was, and I'm not an interrogation specialist, I'm an analyst, but our goal was not to bring pain. Our goal was to convince someone that they should speak. But my question is broader - it's about values."

"If you narrow what we did, no information versus pushing someone against a wall, what would you say? Is that okay?" he adds.

But he says the American people have made it clear they don't like what happened.

"I would argue against judging what happened seven or eight years ago. The world was hot and heavy and you can't remember what it was like to live then. But right now the people have spoken," Mr Mudd says.

He adds: "It's not a question of whether it's torture or not, they say this doesn't reflect where we want to be as American people and I'm comfortable with that, as a public servant. So let's not do it."

Blitz v 9/11

But Mr Mudd also argues that the information obtained this way was of critical value: does that mean if there was another horrific attack, the times would again be hot and heavy, and the pendulum would swing back?

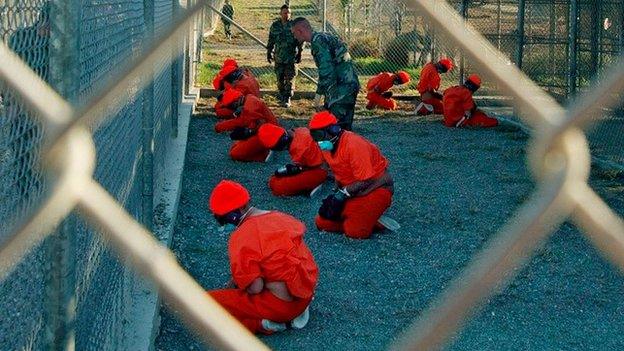

Former prisoners at Guantanamo Bay have said they were subjected to inhumane torture

"No. What I'm saying is that I'm comfortable where we are today," Mr Mudd says.

"If we had another event, and people started swinging the pendulum back and saying, 'lets return to where we were.'

"If I were in the system, and I'm not anymore... I would say, 'look, we've been there'. I don't think this would ever happen again, by the way, not the event, but the reaction'.

"I would say, 'look, we've been down this road. I think the American people have already spoken. Let's keep our shorts on, heads up, chins forward and move on, but not return to the past.'"

The US is not the first Western country to resort to torture. The British did in Malay, Kenya and arguably Northern Ireland, among other places.

But America is the first place to have an open debate about whether it can ever be right.

Such discussions are the meat and drink of adolescent debating societies, rather than mature democracies - where it is more normal to assume it is very wrong, while very occasionally turning a blind eye if it happens.

It has always intrigued me that when Britain really stood in peril of foreign conquest, when the blitz was killing more people than died on 9/11 night after night, it seems torture was not used.

Perhaps they simply never captured a Nazi senior enough to be worth putting to the question. What is the tipping point ?

But is torture ever right? Your turn.

- Published9 August 2011

- Published4 August 2011

- Published10 December 2014

- Published25 October 2010