9/11 hearing proceeds in bite-sized chunks

- Published

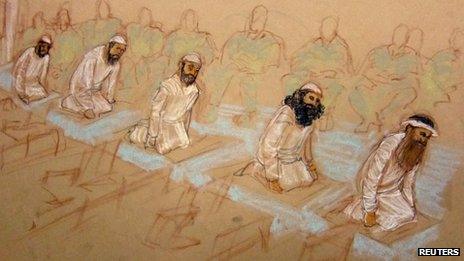

All five defendants joined in courtroom prayer

The first Guantanamo hearing for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four others accused over the 9/11 attacks turned into a series of disputes between defendants, lawyers and the court, writes the BBC's Steve Kingstone.

As courtroom dramas go, this one veered wildly between suspense, tragedy, farce and black comedy.

Early in the hearing, one of the accused, Ramzi Binalshibh, got up from his chair and began to pray.

"When detainees stand up, the guards get excited," observed the judge, Col James Pohl, with studied understatement.

Proceedings were interrupted for several minutes as the defendant continued his prayer, kneeling on the courtroom floor.

Another alleged terrorist, Waleed bin Attash, had begun the day restrained in his chair.

"Can I assume he was not coming here voluntarily today?" asked Judge Pohl drily.

With the defendant apparently in discomfort and unable to reach his headphones, his defence lawyer offered a guarantee.

"He has assured me he will not misbehave if the restraints are removed," explained Captain Michael Schwartz. The judge concurred.

Testing the limits

Before long, however, it was clear that none of the accused was wearing the court-supplied headphones providing simultaneous Arabic translation.

A number of relatives of 9/11 victims attended the court hearing

After a recess, the judge accepted the prosecution's offer to bring an interpreter physically into the court, to relay proceedings aloud in Arabic. "We'll have to do this in bite-sized chunks," Judge Pohl advised.

Therein followed several hours of painfully slow legal back-and-forth.

First, over whether the defendants recognised their court-appointed defence lawyers. Next, whether civilian lawyers were suitably prepared to assist to the defence, in a military case that could carry the death penalty.

And finally, over whether Judge Pohl was sufficiently removed from the events of 9/11 to oversee the biggest terror trial of our times. He was asked by defence lawyers to confirm that none of his family had been killed or injured in the attacks.

At one point during the morning, the video feed to watching reporters was briefly cut, as the hearing took a turn towards matters considered sensitive or classified. Such interruptions have been strongly challenged by the defence and human rights groups, who call them censorship.

When the feed resumed, we were given clues as to what had transpired. "The warning light went off because the word 'torture' was used," observed David Nevin, the civilian lawyer for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.

"I'm trying to work out where the line is," observed Captain Schwartz, the lawyer for Waleed bin Attash. He added wryly that it appeared as if the line was drawn at "embarrassing for the government".

Tiny acts of resistance

All of which presents the defendants with a problem.

If, as appears to be the case, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed wants to argue that this entire process lacks legitimacy because he was water-boarded before being brought to Guantanamo, he will want the world to know about it.

Judge Pohl conducted proceedings in "bite-sized chunks"

But unless the rules are changed, the details may never become public.

The alleged mastermind of 11 September spent much of the day hunched over a desk, looking older than his 47 years.

His silent defiance was a far cry from past theatrics here. In previous appearances he had boasted of having plotted 9/11 "from A to Z," proclaimed that he wished to die a martyr, and even ordered a court sketch artist to redraw his nose.

This time, acts of resistance were small and presented through lawyers.

David Nevin, representing Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, complained that his client had not been allowed to wear the clothes he had brought for him.

Instead, the Guantanamo authorities had stripped-searched the defendants, then supplied them with white Pakistani-style dress.

Virtually all the defence lawyers chipped in with criticism, collectively implying that the enforced dress code was a control tactic.

Long after night fell, the session ended with a formal reading of the charge sheet, which details the steps these men allegedly took to plan mass murder.

It also lists the 2,976 people killed on 11 September 2001, some of whom had relatives watching in court.

Several had told me they were here to bear witness to justice. But even if this court is to offer closure, on this day's evidence it will be a long time coming.

- Published5 May 2012

- Published30 April 2013

- Published3 May 2011

- Published1 September 2011

- Published4 April 2012

- Published1 March 2012