US pivots, China bristles

- Published

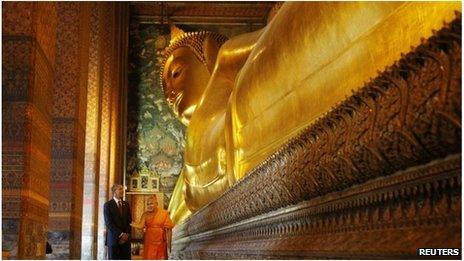

Barack Obama's first stop was in Thailand, a sound US ally

President Obama's Asia trip contains two messages that could be summed up, like some martial-arts pose, as "pivoting with an outstretched hand".

Perhaps it started just as a date in the diary, but Mr Obama is keen to point out that his first foreign visits since the election aren't a mistake. They're a message.

His national security adviser Tom Donilon told a Washington conference, external last week that the President decided early on in his first administration that the US was "underweighted" in some regions and "overweighed" in others, like the Middle East.

The ugliness of the phrase shouldn't disguise the importance of the president's belief that the Pacific region is of a greater strategic value to America than other parts of the world.

Donilon said: "The United States is a Pacific power whose interests are inextricably linked with Asia's economic, security and political order. America's success in the 21st Century is tied to the success of Asia."

He defines this in economic, diplomatic and military terms.

Asia is one part of the world that still has economic growth, and the American recovery depends on that continuing. The president is trying to establish various free-trade agreements with countries in the region.

Asia is also the arena for a struggle between the world's only two super-powers. Ideology and power are at stake. Perhaps even the future direction of the whole world.

The US does not grant China any equivalent of the Monroe Doctrine, external, the 19th Century declaration that other powers shouldn't interfere in the America continent.

Far from it. America is beefing up its military presence with a new base in Australia and fresh agreements with the Philippines and Japan. The message is that smaller countries worried about China's new-found interest in the "near abroad" (to coin a Soviet phrase) have a big and heavily armed friend.

But this is not just about battleships and disputed islands, although there are worrying echoes of past conflicts. It is more a conflict of ideas, contained within a mutual embrace. Obama is keen to portray China as a potential partner or a friendly rival rather than an enemy. But strip away the warm rhetoric and it is hard not to see a clear challenge to China's view of the world.

Donilon summed it up: "Our overarching objective is to sustain a stable security environment and a regional order rooted in economic openness, peaceful resolution of disputes, democratic governance, and political freedom."

Parts of Rangoon are well-prepared for the first-ever visit of a US president

I didn't hear much about the last point in Xi Jinping's speech when China's new leader was unveiled last week. But it is at the heart of the most high-profile part of Obama's visit, the historic trip to Burma.

Domestic opponents have mocked President Obama's policy of engagement, stretching out a hand of friendship to those who might be considered enemies. They say it has failed with Russia and failed with China.

But one place it has succeeded is Burma. The tentative liberalisation undertaken by hard-line rulers of one of the most authoritarian countries in the world is amazing.

The US has been criticised for engaging too far and too fast with Burma. However, the president's visit is not only a reward for what they have already done, but also an encouragement to do much more. He comes with a long shopping list detailing what must come next.

China under Xi Jinping will regard the US pivot as a threat

Donilon said US demands included "unconditional release of remaining political prisoners, an end to ethnic conflicts, steps to establish the rule of law, ending the use of child soldiers and ensuring the safety and welfare of the people of Rakhine state".

There is also a veiled threat - the Burmese government is not the only group the US will work with. They will also work directly with opposition groups, backing demands for the rule of law and human rights.

This is a promise to support the liberalisation of a country that is right on China's doorstep and which has been its faithful client and steadfast ally.

As China's new leaders restate their determination to resist Western notions of democracy, this is bold, almost cheeky.

No doubt while on his trip the president's gaze will be forced back to the Middle East, overweighted or not.

But I have little doubt it will only confirm his preference to be a Pacific president, focused on the region where the battles of the future are being fought rather than on the continuing aftershocks of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and Europe's wars.

- Published9 November 2012

- Published8 November 2012

- Published9 November 2012