Viewpoint: The invisible plague of concussion

- Published

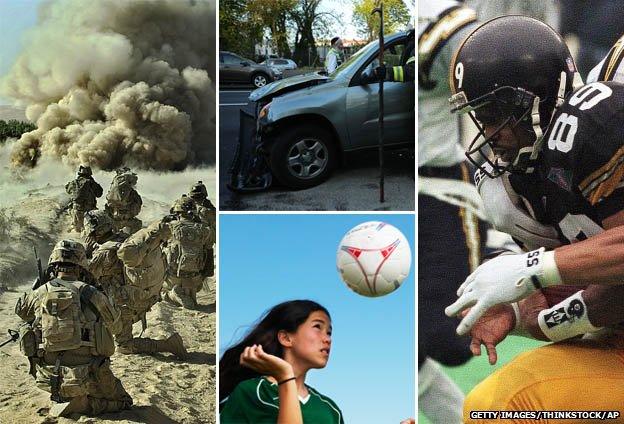

Traumatic brain injury is a hidden epidemic in the US, reaching beyond American football to wounded military veterans and girls' soccer players. Neurosurgeon Dr Anand Veeravagu outlines concussion's potentially devastating side effects.

It is all too common for patients to tell me that they have been knocked out while playing sports or in an accident. But the consequences of concussion, or "getting your bell rung" as the disarmingly quaint expression goes, can prove disastrous.

As Chief Neurosurgery Resident at the Palo Alto Veterans Hospital, I've treated many of our nation's service members, some of whom came home with injuries that changed their lives forever.

I will always remember in particular one US Army soldier in my care. Mitch (not his real name) was nearing the end of his deployment in Afghanistan when his convoy was hit by a roadside bomb.

His vehicle's heavy armour shielded most of his body from the blast and saved his life. But it did little to protect his brain. Despite the very latest in helmet technology, the powerful shock waves of such a blast hitting a vehicle often wreak havoc on soft brain tissue.

At a battlefield hospital in Afghanistan, Mitch underwent an emergency procedure called a decompressive craniectomy, where surgeons removed a 13-in (33-cm) piece of his skull to help make room for uncontrollable brain swelling.

This is a fairly common strategy for treating patients with severe head injuries.

A similar surgery was performed on US Representative Gabrielle Giffords when she suffered a bullet wound to the head in 2011. After Asiana Flight 214 crashed in San Francisco in July, passengers who suffered blunt-force head trauma also underwent the operation.

I performed Mitch's final surgery, a cranioplasty where we used special implants created by 3D printers to reconstruct the fragmented bones of his skull and restore the natural shape of his head.

The procedure also allowed him to ditch the heavy protective helmet he had to wear. Mitch came through the operation extraordinarily well.

His family pictures are now of him, without a helmet, embracing his children. Yet his injury is a stark reminder of how destructive brain injuries can be.

Mitch's case, unfortunately, is just the tip of the iceberg. More than 260,000 of America's veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan have been diagnosed with traumatic brain injury (TBI), the invisible wound of war.

And yet these numbers do not come close to capturing the extent of head injuries suffered by the wider American population.

This year alone, the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that over 1.7 million Americans will suffer a traumatic brain injury, whether a mild concussion or something more serious.

During the last decade, emergency room visits for sport- and recreation-related TBIs among children and adolescents increased by almost 60%.

After American football, girls' soccer is the fastest-rising category of teenage TBI.

Brain injuries and neurological illnesses have been termed America's silent epidemic.

Stephen Sackur talks to the Olympic rower, James Cracknell.

And it is not just a US problem - researchers in Canada recently reported that an estimated one in five teens had suffered a TBI that required admission to hospital or caused them to become unconscious for at least five minutes.

The saddest statistic is that many of these potentially life-altering injuries could have been prevented.

Every individual experiences a brain injury differently. Loss of consciousness, headaches, transient memory loss, slowed cognition, ringing in the ears and nausea are just a few of the symptoms that may or may not be present at the time of an injury.

Often, these symptoms are so abstract that the diagnosis of TBI proves elusive to patients, parents and doctors.

With increasing evidence indicating multiple brain injuries are related to depression and Alzheimer's, the potential side effects of such symptoms are too grave to ignore.

The most powerful treatment for brain injuries is prevention and, failing that, early intervention. Rest, clinical exams and therapy are critical to restoring cognition, thinking and brain power. The earlier a concussion is recognised, the better the prognosis - something that is especially true in children.

The attention captured by the class-action lawsuit against the National Football League suggests the public is becoming increasingly concerned about the effects of repetitive brain injuries.

As the new NFL season gets under way this week, that legal action is currently working towards a $765m (£490m) settlement.

Dozens of US states have passed laws similar to one introduced in the US state of Washington in 2009, under which young athletes who suffer a suspected concussion in sport must be cleared by a medical professional before being allowed back to the game.

Until we as a nation appreciate the importance of brain health, America's headache is unlikely to get better.

DrAnand Veeravagu (@AnandMed, external) is a former White House Fellow/Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense and currently Senior Neurosurgery Resident at Stanford University. His views are his own and do not reflect those of any institutional entity.

- Published29 August 2013

- Published13 September 2012

- Published3 August 2013

- Published4 May 2012