US and China's tug-of-war over Koreas

- Published

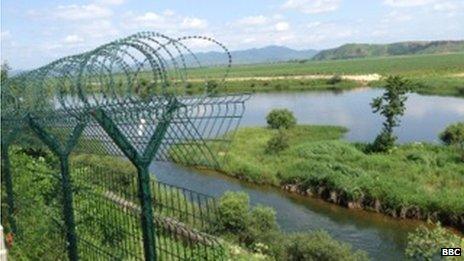

Tourists frequently flock to North Korea's imposing border with China

A soldier gestures towards our boat, which is idling just a few metres off the North Korean shore.

The man, dressed in a thin brown uniform a little bit too big for him, is not threatening us for coming too close, but pleading. Repeatedly, two fingers go to his lips - the global sign language for "have you got a smoke?"

We have. The captain throws him a packet of 200. He hurries forward, scooping them off the ground and in a single motion stuffs them inside his tunic, then marches off at a sharp pace in an unsuccessful attempt at nonchalance.

The lush emerald green hills rise sharply from the North Korean shoreline, a few sparse patches of corn growing up its side.

You can spot the occasional goat and field worker, but there are far more soldiers. Ugly concrete pill boxes with lookout slits sit among the vegetation.

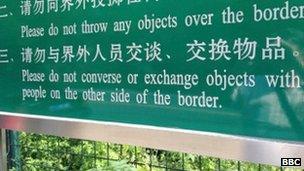

North Korea is one of the most mysterious, isolated countries in the world, suffering a self-inflicted locked-in syndrome. But along the Yalu River, the natural border with China, this benighted country is just one more sight for Chinese tourists.

Boatloads of them gawp at the forbidden shore. Mao said North Korea and China should be as close as lips and teeth, but now they are pulled into a grimace.

I've come here to make a documentary for BBC Radio Four and the World Service on the relationship between the United States and China, and there is no doubt North Korea is one of the places that test my title: Harmony and Hostility.

US President Barack Obama and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, may have announced that their countries have a new relationship, but there's little sign of it at another spot on the tourists' itinerary.

'Relic of the past'

A museum in Dandong, China, commemorates what it calls The War Against American Aggression

Dandong's museum commemorates what it calls The War Against American Aggression, which forged North Korea and ended 50 years ago this summer. It is very much a relic of the past.

As you drive in, there are American tanks, Soviet MiG jet fighters, guns and howitzers. An obelisk bears the museum's title in gold Chinese characters.

Around it are statues of brave Chinese soldiers, airmen and workers cradling their dead, trampling the American enemy underfoot.

Inside, one woman visitor tells me: "We really respect our soldiers, their performance in the battle. And we really hate war; we just don't want that the war happens again."

So I ask if she trusts the Americans now.

"I don't like America very much because it's always the start of the wars in the world - look at how many wars started right now. Because I think we really want more peace in the world."

The city of Dandong itself is an appealing place.

Certainly some of the buildings look old-fashioned and have seen better days. It's a bit gritty, somewhat faded around the edges. But it is testimony to China's continuing economic miracle.

There's a sense of vigour, of hustle and bustle. Motorbikes with improbable projections out front and back, carrying ladders, tea urns or bits of scaffolding, thread a precarious route between the often stationary, always honking traffic.

The yellow taxis bear signs on their roofs of scrolling Chinese characters advertising financial services and insurance.

By the street, men and women squat behind rugs carrying their produce, a pile of fresh lychees in their dusky red skins, pale aubergines and live chickens in cages.

At night the restaurants along the promenade turn on their neon lights, and people exercising to Chinese music are lit by the vivid glow from the blues and greens and reds of the Sino-Korean friendship bridge as it heads apparently into the void.

'Bridge to nowhere'

The bridge alongside it literally heads nowhere. It was bombed in the Korean War and never repaired, ending abruptly, cut off mid-river.

But the working bridge, busy during the day with truck traffic, simply appears to go nowhere because the North Korean town on the other bank is all in darkness; not a single light to be seen.

A bridge between Dandong, China and North Korea facilitates business interests

I talk to a Chinese businessman, Dong Feng. His cotton sweaters may be labelled Made in China, but they're actually manufactured in North Korea. And his biggest markets? Japan and the United States.

He says it is about 40% cheaper to make the clothes in North Korea because of lower labour costs. But as a businessman is he worried about the political situation?

"Yes. We have lots of concerns. The condition in the Korean peninsula matters to every businessman directly. So we are very cautious. Personally, I think the chance of war in Korean peninsula is close to zero, despite the obvious tension."

I ask about the relationship with America - can there be friendship with China?

"The relationship between countries is just like between two kids," he says. "They're always fighting for their own interest.

"We have an old Chinese saying: 'There is no such thing as eternal friends, only eternal interests.' As long as there are common interests for the two countries to pursue, their friendship will be maintained."

And there is a common interest over North Korea. China has been much tougher this year on its old ally, both in words and actions.

There are real sanctions on banks and the North Korean leadership has been publicly warned about creating tensions on China's doorstep.

Prof Xie Tao of Beijing's Foreign Studies University told me North Korea - the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) went too far. Those nuclear tests, and the ranting threats that went with them, were the final straw for China.

He says: "After the third round [of tests], the Chinese government finally realised you have a nuclear armed neighbour which is so close to China's north east - one of the most important agriculture and industrial basis - that's a real danger to China.

"You already have Pakistan and Russia, so if you have another nuclear power on your border, China would be in probably the worst security situation in the world," he added.

"We ran out of patience. We did give a lot of time and chance to the DPRK leadership.

"We expected them to adopt a China-type economic reform. But so far, the signs have not been very encouraging at all.

"Also, the behaviour of DPRK leadership has been extremely unpredictable. If you don't have credibility, how can other people trust you?"

Co-operation or co-incidence?

China's patience with North Korea has reportedly waned following nuclear tests

The nuclear issue is of course the main problem, but it is fairly certain that North Korea's failure to learn the lesson of China's growth is a source of irritation.

That is very visible a few miles down river in New Dandong District. There could hardly be a greater contrast with the old city's chaotic vibrancy.

Stiff and lifeless identical skyscrapers rise in ranks from the virgin ground next to the river. This is a pristine ghost town. I've seen nothing like it since visiting a Spanish estate built before the crash.

But this is on a much bigger scale, and the planned building is still going on. There are a couple of very big concrete clues to the reason for the absence of economic life.

Two gigantic H-shaped spans, the beginnings of an immense new bridge, stick out from the river.

Meant to link China and North Korea, the planned new economic area was a limited experiment in liberalisation. But it never happened and work on the bridge has apparently stopped.

China's leaders prize two things above all others - growth and stability. North Korea provides neither, says Shi Yinhong, a professor of international relations at Beijing's Renmin University.

He even says that North Korea is no longer China's ally.

"Peace is China's number one interest, and vital interest," he says. "If North Korea does ugly things and threatens its neighbours, this is very dangerous."

"We still have some strategic interests, even vital strategic interests, in the peninsula and with relations with North Korea. But they are not our ally now," he adds.

"How can an ally take such an extremely unfriendly attitude toward China? And do things again and again which obviously are damaging China's interest."

When it comes to this troublesome regime, China is now largely doing what America wants. But is that co-operation or co-incidence?

'Warmongering'

Joseph De Trani is a good man to ask. Between 2003-06, he was US ambassador to the now-stalled six-party talks aimed at denuclearising North Korea.

"I think part is the US factor. But they are not just going to jump because that's what the United States wants. They're going to initially decide what's in China's interest.

"That's point number one. Point two, however, is to ensure that the issues of United States are also addressed," he added.

But America has to be careful.

It puts pressure on North Korea by beefing up its military presence in the region and strengthening armed alliances with countries like Japan, the Philippines and, of course, South Korea.

That is something that the Chinese look on with wary distaste, and can see as a threat.

Prof Ruan Zongze is a former senior diplomat to Washington and London. Now he's vice-president of the Chinese Institute for International Studies, the think tank of the Chinese Foreign Ministry.

"When Americans say they will conduct numerous military exercises here in order to check North Korea," he says, "and also try to send a message to China, be honest. So the message is, if you don't want this, put pressure on [North Korean leader] Kim Jong-un.

"I don't think this will work. As a matter of fact, it's counter-productive because more military muscle show over here will reduce the desirability for the Chinese side to be co-operative, because it is a kind of warmongering at China's doorstep," he adds.

"Certainly this is not the right approach to send a positive message to the Chinese."

But I suggest it works.

"No, its not working. Maybe some people say this is the result of America's pressure. Certainly not, I don't think so. How China should operate our policies under the pressures of Washington; it's no way for that. It's getting more and more unacceptable for this, because you invite more backlash from China," Mr Zongze says.

A price worth paying?

In the motorboat on the Yalu River, we speed by a North Korean military camp, a rather wonky communications tower sticking out of a concrete block of a building.

A North Korean military camp on the border is a reminder of tenuous relationships with its neighbours

On the other bank, you can see part of the Great Wall of China in the background, snaking down the hillside, a grand edifice meant to keep out the barbarians.

This is only a tiny part of the border between the two countries, which is about as long as the United Kingdom, 560 miles (900km).

It brings home the importance of what is at stake. One thing the Chinese could never accept would be American troops here on the Yalu River, on their borders.

But that is the risk if North Korea collapsed and the peninsula was unified under a South Korean-style government - a strong ally of the Americans.

And yet, what if a neutral, peaceful, denuclearised unified Korea robbed the US of its main reason - excuse if you like - to keep a strong military here?

The collapse of a one-time ally might be a price worth paying for China if "the Yanks" go home.

Tomorrow I'll be looking at the view from Beijing, and the wider relationship between the US and China.

"You can listen to Mark Mardell's China and America: Harmony and Hostility on BBC Radio 4, 10th September 2013 at 8pm."