Syria debate in US Congress could break a president

- Published

This week, and the one that follows, could be the days that break a president.

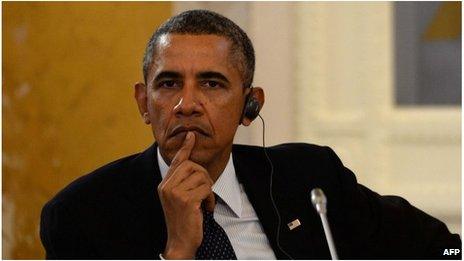

If Barack Obama escapes humiliation that will be enough - there is no sense that even victory in Congress will leave him in an enviable position.

The next few days will see Mr Obama stripped, all the flaws of his presidency on display, all the strengths of his personality strained to their limit.

His dazzling way with words, his skill as an orator, is beyond doubt. They will be deployed to the full, in the six big TV interviews he has planned, in the address to the nation on Tuesday night.

But recently his words have lost a little of their ability to glamour the listener. The magic has faded with repetition. In some, familiarity has bred contempt.

Even worse for him, the words that are the most important are the hardest. They are the ones he speaks in private, on the phone or in person, to the politicians who hold his fate in their hands. And he's been notoriously bad in persuading Congress of anything.

He ignored the groundwork for years. This a city where, far more than in British parliament, the political is personal.

Just about every senator, every representative has a keen sense of their own importance. Any one would find attention from the president flattering. To those who deal in power, it is currency.

Buttering up an ego today can grease a deal tomorrow. But Mr Obama doesn't like glad-handing, back-slapping and inquiring after sick spouses. He hasn't built up the relations that would allow him to cajole and threaten.

But it is worse than that. Most of us are best at persuading others when we feel passionate about a cause. Listen to President Obama in St Petersburg and it is not always clear that he has persuaded himself.

Battle of instincts

That is perhaps unfair. He has decided on a course of action, but only after coming to the end of a long and agonising journey, embarked on reluctantly. It has taken him somewhere that can seem very far from his instincts and nature.

In his Swedish news conference he indicated he would much rather be dealing with the problems of a poor child's education than matters of war and peace. After all, he was elected to put the home front first, and to end America's wars.

The president has yet to convince the American public to back military action

To many at home and abroad his priorities are a sign of maturity and strength. But it is not exactly Churchillian.

Mr Obama is one of the few politicians who display their internal workings, and that has its charm.

But it is not only the Prince of Denmark's soliloquies that are a reflection of indecision, that blunt actual action. Battling it out inside the president's soul there are at least three instincts.

There's an emotional desire to avoid war, strengthened by a political imperative to do so for domestic reasons and an intellectual conviction that America mustn't and shouldn't impose its will on the world.

There's the desire, lit by his admiration for the Civil Rights movement, to stand up for the weak, the oppressed and those denied a say in governing themselves.

Then there's the commander-in-chief, whose prime duty is to protect America and its long-term interests in the world.

The interplay between these strands led him to fight shy of involvement in Syria in the first place, but then announce red lines on chemical weapons. They caused him to back away from action when the lines were first breached, and then rather reluctantly return to them, stressing that this wasn't about regime change. When others, including the UK, declined to share his view he turned to Congress.

It is possible his many critics are wrong and he alone has taken a wise course, against the odds. But at the moment this all looks like a mess heading for a political disaster.