Will Congress ever learn its lesson?

- Published

- comments

The statue of Grief and History stands in front of the US Capitol Dome in Washington on 16 October 2013

After the horrific mass murder at Newtown, Connecticut's Sandy Hook Elementary School in December 2012, there was a tremendous amount of conversation that this had to be the moment of change in how America coped with gun violence.

Finally the politicians and the citizenry would take on the gun lobby and there would be gun control legislation, well-funded enforcement and new attitudes.

That change, we now know, never came.

Having covered American politics, government and culture for well over 30 years, I was the jaded sceptic in this mostly British newsroom who predicted the Newtown moment would fade away.

Similarly, today there is a tremendous amount of conversation about how this latest national embarrassment over debt ceilings and budget deadlines will finally force Congress to grow up and govern with some modicum of orderliness and common sense.

Zero-sum games

Again, the sceptic says don't hold your breath. Actually, I am more sceptical than that.

Republican Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell: "This has been a long, challenging few weeks"

And I am impressed by the thoughts on this possible turning point from two other sceptics, Robert Samuelson and Lawrence Summers.

Samuelson is one of our best and most senior economic columnists. He does see the current piece of governmental auto-vandalism as a turning point - the bad kind.

"When the history is written, I suspect the brutal budget battle transfixing the nation will be seen as much more than a spectacular partisan showdown," Samuelson wrote in the Washington Post, external earlier this week.

"Careful historians will, I think, cast it as a symbolic turning point for post-World War II institutions - mainly the welfare state and the consumer credit complex - that depended on strong economic growth that has now, sadly, gone missing."

In the absence of economic growth, Samuelson argues, political decisions are always zero-sum games and are always harder.

He doubts our political institutions are strong enough and well-managed enough to cope with the end of growth, much less revive growth.

'Dysfunctional'

I would add that the major institutions in the corporate and finance worlds are equally weak and short-sighted.

On the same op-ed page, external, former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers also argued that this debt and budget battle is a turning point - also the bad kind.

Summers says "future historians may well see today's crisis as the turning point at which American democracy was shown to be dysfunctional - an example to be avoided rather than emulated."

Neither Summers nor Samuelson believe this turning point is a wakeup call. Just a bad omen.

Others are more hopeful.

So as the post-mortem examinations on "Boehner's Bungle" come in, expect to hear talk about how the pendulum always swings back to the middle in American politics; about how Tea Party flamethrowers in the GOP will be ousted by sober country club, Eisenhower Republicans; about how Democrats reach out to temper some of the partisanship that has given this Congress the lowest approval ratings in history, if only to save their souls.

Don't hold your breath.

American political institutions functioned quite well from the Depression until the 1970s.

But since then relentless waves of partisanship, special interest money, media trivialisation and declining trust have eroded the foundations of those institutions.

Institutions beyond politics, such as Wall Street, corporate America and the press, have been no less affected.

If Samuelson is correct that economic growth at post-war levels will never reappear, the system will be further stressed.

Fantasyland

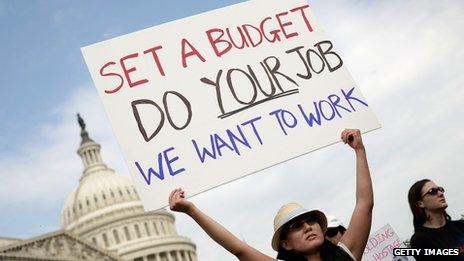

A furloughed federal worker protested outside the US Capitol during the 16-day government shutdown

What would have to happen for this to be a political turning point - the good kind?

What would have to happen to attract our most talented people back into politics and then create a fresh capacity in government to make difficult but orderly long-term decisions?

Now we're in fantasyland.

But as long as we're here, I'll mention two scenarios.

My pet fantasy, perhaps because I work for a British organisation, is that a small third party could gain enough votes in Congress and potential sway in presidential elections to force a new type of coalition building, more akin to a parliamentary system or pre-Civil War America.

Such a party would probably be moderate in today's nomenclature, Bloombergian in some ways.

The other scenario is that somehow parties regain power and discipline over their membership and over the special interests that finance their operations.

This would entail reform of the primary system and campaign finance reform. It would entail incumbent politicians going against their short-term career interests.

Fantasyland, like I said.

And sadly, just as with Newtown, this is no turning point of the good kind.

- Published7 October 2013