Iran hostage crisis wounds linger for US government

- Published

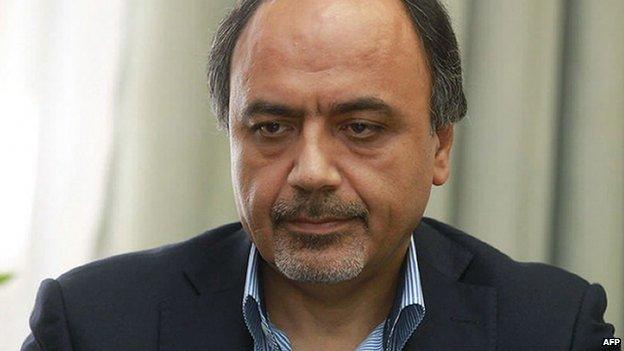

Aboutalebi has said he served only as a translator for the hostage takers but was not among the initial group who raided the embassy

The duelling parties in the US Congress may not agree on healthcare or anti-poverty measures, but they can agree to ban an Iranian envoy.

Iran policy has been a unique zone of detente in Washington's take-no-prisoners partisan politics, and nowhere has that been more evident than in the case of Hamid Aboutalebi.

When Iran's choice for UN ambassador was revealed to have played a role in the 1979 hostage crisis - as an occasional translator, by his account - Congress swiftly passed legislation banning UN visas for anyone deemed an anti-US terrorist.

Politically, that left the White House little choice but to bar him from the country.

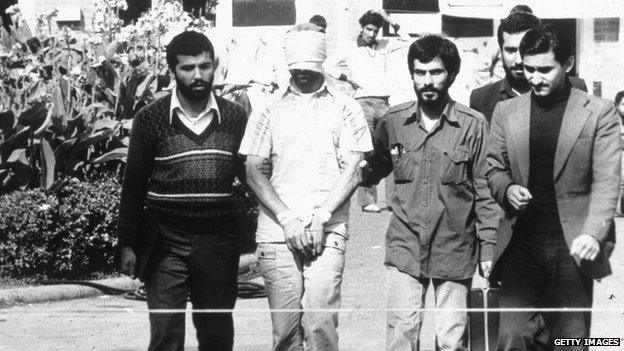

As one of the first major televised foreign policy crises in US history, the 14-month captivity of 52 Americans at the US embassy in Tehran engraved itself on the memory of every American who lived through it.

It has festered at the heart of Washington's relations with Iran ever since.

"I suppose it was the outrageousness of it," says former hostage John Limbert, in particular that a government would end up supporting the young revolutionaries' audacious act.

The hostage crisis may still set off emotional alarm bells here, but it's also become a political football, one that some believe was played by members of Congress suspicious of negotiations on Iran's nuclear programme.

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have often felt left in the dark about the talks, conducted by six world powers and aimed at ensuring Iran's nuclear activities are peaceful.

"This was an opportunity for people who were unhappy with the administration and the whole negotiating idea to come out and attack the administration, to raise a fuss," says Gary Sick, who was the principal White House aide for Iran affairs during the hostage crisis, and is now a professor at Columbia University.

"Congress has been trying to insert itself into the negotiation process with Iran and has taken exception to a lot of the things this administration was doing."

At the forefront of those efforts was a US Senate bill outlining onerous new sanctions, should the talks fail, and presented as a "diplomatic insurance policy" to strengthen President Barack Obama's negotiating hand.

Fifty-two Americans were held for 444 days at the height of Iran's Islamic revolution in 1979

'March to war'

Instead, administration officials feared it would set him up for failure.

The pro-Israel lobby brought its considerable bipartisan influence to bear in pushing heavily for the bill, to the extent that one of its co-authors, Republican Senator Mark Kirk, called it a "test issue for the pro-Israel community".

But with the White House characterising the move as a "march to war", most Democrats dropped their support and the bill was shelved.

A draft bill currently in the works that would target the financiers of Tehran's Lebanese ally Hezbollah is seen by some as a way Congress can stay relevant.

It's a way to pressure Iran without directly imposing new sanctions during the negotiations, a congressional aide told the BBC.

Senator Ted Cruz drew on this body of political calculation and suspicion when denouncing the Aboutalebi appointment.

"It is part of Iran's clear pattern of virulent anti-Americanism that has defined their foreign policy since 1979," he said.

"Given the larger strategic threat to the US and our allies represented by Iran's nuclear ambitions, this is not the time for diplomatic niceties."

Still, says the congressional aide, this was not only about politics. Lawmakers genuinely found the move insulting and saw it as symbolic of Iran's disrespect for America.

Analysts have also been scratching their heads at the choice by Iran's President Hassan Rouhani, who has shown more interest than his predecessors in engaging the West.

They suggest he was focused on finding an accomplished diplomat to fill the important UN role at a critical time, and appeared to have underestimated the strength of American reaction to even a minor connection to the hostage crisis.

As the host country of the UN, the US is legally obligated to accept representatives appointed by member states. In practice it has denied visas before - including to Iranians associated with the hostage taking - but those cases were resolved quietly.

This spat became unusually public, with Iran refusing to rescind the nomination and officially complaining to the UN.

Rouhani may have underestimated the vehemence of the US reaction, analysts say

'Ghosts in the room'

The diplomatic row has the potential to disrupt the nuclear negotiations, but early indications are that it may not, with the UN committee handling the affair taking no immediate action.

The Iranian government is heavily invested in securing a deal, according to diplomats involved in the talks, and Mr Obama seems willing to expend political capital to get one.

Mr Sick sees this as an unprecedented period of equilibrium in 35 years of turbulent relations.

"Things have really changed," he says, noting that US and Iranian officials who once communicated through secret talks were now openly emailing each other.

In the end, however, Congress will have the final say, because there won't be a nuclear agreement without congressional action to lift sanctions.

And even if it does, says Iranian analyst Trita Parsi, the ambassador row suggests "the resolution of the nuclear issue [wouldn't automatically] fundamentally transform the relationship" and dispel the deep-seeded mistrust left in America by the hostage crisis and in Iran by US support for the 1953 coup in Tehran.

"It's like ghosts in the room," says Mr Limbert. "You ignore them, but they still haunt you. They're still there."

- Published23 April 2014

- Published18 April 2014

- Published15 April 2014