New voices challenge Cuban-American support for embargo

- Published

Little Havana offers Cuban exiles many of the sounds and flavours of home

For decades Florida's Cuban-American residents voted as a bloc around issues relating to US-Cuba relations. Now, the younger generation appears to be yearning for more contact with the island of their fathers and mothers.

Miami is a North American city with a Latin American feel, and at Domino Park in Little Havana old men gather each day to recreate a small corner of their beloved homeland.

Hunched over small tables, they wile away the afternoon playing dominos and chess, some wearing Panama hats, others donning baseball caps - a sartorial indicator of the dual allegiance of the Cuban-American community. Many of them are old and frail. Yet ask them about the communist Castro brothers, Fidel and Raul, and the passions of their youth are easily aroused.

"He's not a good man," says one elderly gentleman, referring to Fidel Castro. "He's killing people in Cuba, my country."

A whistle-stop tour of Little Havana takes in the murals on the walls that celebrate the anti-communist crusade, the shops selling fat, premium cigars, and the local barber, where clients are draped with aprons adorned with the Cuban flag.

No visit is complete without pausing at the memorial plaza, commemorating heroes of the Cuban independence struggle in bronze. There is also a giant map of Cuba, with an inscription from the poet and patriot Jose Marti: La patria es agonia y deber. It translates as: "The homeland is agony and duty."

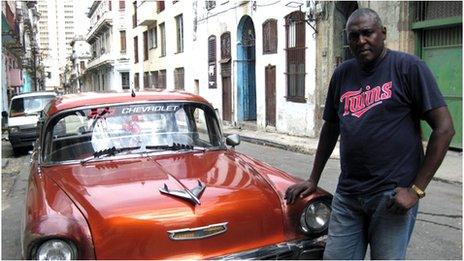

Jorge Perez says the embargo is no longer effective

Then it's off to lunch at the Cafe Versailles, a vital stopping-off point for candidates courting the Cuban-American vote. The longstanding influence of this lobby stems not so much from its size as its unity and concentration in Florida, a key battleground state in presidential elections.

But there are signs that the political rules that operated for the last 50 years are starting to change.

At the elegant new Perez Art Museum in Miami, designed by the same architectural firm behind London's Tate Modern, we met the billionaire businessman Jorge Perez, who paid for much of its construction.

Perez, one of Miami's most influential figures, is calling for the US's strict embargo on Cuba to be lifted.

"I strongly believe it's a failed policy," he says. "Lift the embargo and start a policy in which there's a lot more communication all across the spectrum: government with government, non-profits with non-profits, people with people, in order to show why our system is the best system in the world."

Some people in the Cuban-American community regard that as betrayal, I suggest.

"I think that opinion has died down to a large extent," he says. "And I think you'll find particularly in the younger generation in Miami, that they're looking forward to seeing the land of their fathers and to have a Cuba that is freer."

The embargo came into effect 1960, the year after Fidel Castro took power in Havana. Over time, it ended up banning most exports to Cuba and virtually all imports. US citizens have been prevented from doing business in or with Cuba, and restrictions were also placed on Americans travelling to Cuba.

Recent polling suggests more than half of Cubans living in South Florida favoured normalisation of relations with the island

More than 50 years on, however, the Castros are still in power. US critics of the embargo argue it has crippled the Cuban people rather than the government.

"We're beginning to realise not only the policy didn't work but it was just wrong and counterproductive," says Carlos Saladrigas, another prominent figure in the Cuban-American community.

"The politics of passion is being replaced by the politics of affection," he says. He credits a generational change - the simple fact that so many emigres have died off - and the mounting feeling that the embargo has failed.

In the slow thawing of relations between Washington and Havana, Nelson Mandela's memorial service last year became an inflection point. President Obama shook hands with his Cuban counterpart, Raul Castro - the first leader-to-leader contact since Bill Clinton had a similar brush-by with Fidel Castro at a UN summit in New York in 2000.

The muted reaction to that handshake spoke volumes, according to Carlos Saladrigas.

"Twenty years ago had that happened we would have had a major demonstration," he says.

Cuban Ramon Lara: "In a part, it has affected us. But, at the same time, it hasn’t. What can I say? At the end, life continues. Everybody carries on with their jobs, with their lives, like nothing has happened".

"That was something that indicates a significant change that has taken place in Miami," he says.

Recent polls bolster his argument. One conducted by the Atlantic Council in February showed that 64% of Cubans living in South Florida favoured normalisation of relations with Cuba or more direct engagement. When the poll expanded to those of Cuban descent throughout Florida, 79% favoured normalisation or engagement.

However, leaders in the Cuban American community believe the embargo should remain in place for now.

"It's not time yet," says Francisco Jose Hernandez, the president of the Cuban-American National Foundation.

"Things have to change, and there has to be a significant reform."

That said, he hopes the embargo will be lifted after proof of real progress in Havana, such as Raul Castro stepping down.

The US embargo still has strong support from influential lawmakers on Capitol Hill, among them Democratic New Jersey Senator Robert Menendez, the hawkish pro-embargo chairman of the foreign relations committee and Republican Senator Marco Rubio of Florida. Both are of Cuban descent.

Moreover, written in law is the stipulation that the embargo cannot be lifted while a Castro remains in power.

Still, times are changing in Little Havana. To be Cuban American in Miami once meant supporting the embargo, almost as an article of identity and faith. That is no longer the case.

- Published7 February 2012

- Published11 October 2012

- Published29 March 2012