PJ Crowley: James Foley video not intended for US

- Published

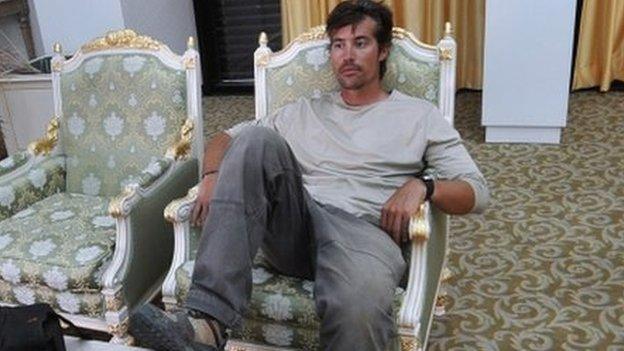

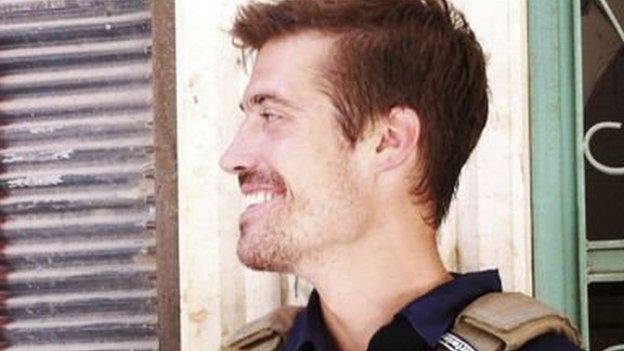

James Foley has been missing since he was seized in Syria in 2012

When President Barack Obama recently authorised a military air campaign against the Islamic State (IS) in Iraq, some form of retaliation was inevitable. The Islamic State's first response is the horrific video showing the beheading of American journalist James Foley, captured in Syria in 2012.

As propaganda, the video seems to reinforce our understanding of the brutal protagonist now at the centre of the conflicts in Iraq and Syria.

But the broader message the video delivers has potential strategic significance.

Almost half of the video is devoted to Mr Obama and his announcement of air strikes against the Islamic State in Iraq. Since the president justified the military action in terms of protecting the lives of Americans serving in and near the conflict zone, the video attempts to undermine that objective.

"You have plotted against us and gone out of your way to find reasons to interfere in our affairs," a man dressed in black says in the video. "Your strikes have caused casualties among Muslims."

The result, he says, is "bloodshed of your people".

Foley, clearly under coercion, says that the American bombing campaign against the Islamic State amounts to his death warrant and potentially the same for others.

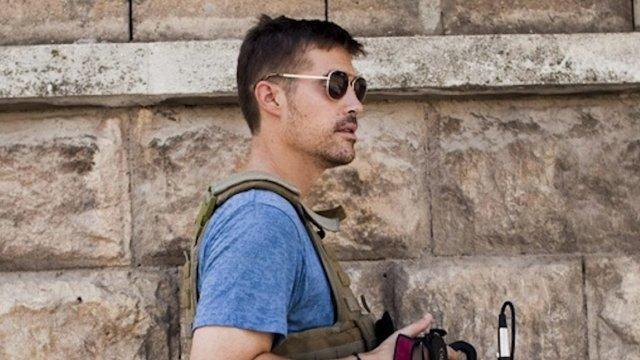

President Barack Obama wants Iraq and other countries to fight extremism inside their own borders

But he undoubtedly knows that his gruesome death, which has yet to be confirmed by authorities, will generate outrage in the West and reinforce the existing strategy.

It is sadly reminiscent of the beheading of Wall Street Journal reporter Danny Pearl in 2002 at the hand of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, now held at the US detention facility in Guantanamo Bay.

But the video's primary target is actually the Muslim world, those who already explicitly or tacitly support the Islamic State or those, particularly westerners, who may be attracted to join the twin conflicts. The narrator (who has a British accent) says their group has been accepted by a larger number of Muslims worldwide.

Taking a page from its previous experience in Iraq, Islamic State wants Muslims worldwide to view the American military campaign as a renewed war against Islam.

US Navy jets land onboard a US aircraft carrier after striking IS targets in Iraq

This is a perception Mr Obama has spent five years in office trying to overcome, beginning with his speech in Cairo to the Muslim world in June 2009.

The Islamic State is unlikely to sway all that many minds through this video. Notwithstanding its stunning successes in recent months, there is little indication Muslims around the world or even in Iraq want to live in such a repressive society.

But it does reinforce the primary concern that governments have about the hundreds and perhaps thousands of young men from the United States and Europe who are now thought to have joined this "army".

The experience they gain in Iraq and Syria, and what they think and what they do once they go home, represents a potential long-term security threat.

This is the dichotomy at the heart of this ongoing struggle.

Since inheriting George W Bush's global war on terror in 2009, Mr Obama has consistently tried to narrow its focus.

He recognises the networked interconnections among extremist groups and the broad diffusion of the threat across an arc from Afghanistan across the Middle East and North Africa to Nigeria.

But he has tried to disaggregate the threat into discrete tactical campaigns - reluctantly forced into overt military action in Iraq while keeping Syria at arm's length, a broad international and regional approach to Nigeria's Boko Haram, and nominally covert campaigns in Pakistan and Yemen.

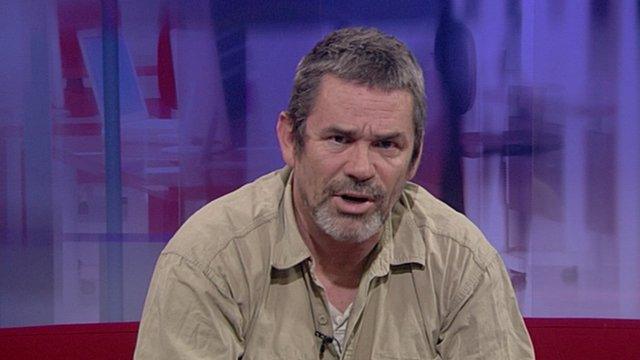

A ribbon is tied to a tree outside James Foley's house in Rochester, New Hampshire

Mr Obama wants to see countries like Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq and Nigeria do more to confront extremism within their own borders.

The US will help with direct action, support and training as partners improve their security capabilities, but his intent is ultimately to avoid a perpetual US-led "war".

In fact, Mr Obama may have hoped at the end of 2014 to declare a formal end not just to the war in Afghanistan, but the broader war on terror as well.

The Islamic State's emergence as the leading extremist actor in the Middle East - supplanting rival al-Qaeda - probably renders that prospect as moot.

America is not re-engaging in the war in Iraq it waged between 2003-11.

But the Islamic State makes clear in its video that it is at war in Iraq and Syria, a conflict that it believes now includes the US.

PJ Crowley is a former US Assistant Secretary of State and now a professor of practice and fellow at The George Washington University Institute of Public Diplomacy & Global Communication.

- Published20 August 2014

- Published20 August 2014

- Published20 August 2014

- Published20 August 2014

- Published20 August 2014