Syria air strikes: Can Obama's Arab coalition hold?

- Published

President Barack Obama is putting together a strategy against IS one step at a time, PJ Crowley says

President Barack Obama has touted the involvement of Arab nations - many of them Sunni-majority - in US air strikes against Islamic State militants. But will this coalition hold up to the scrutiny of their own internal politics?

What a difference a year makes.

President Barack Obama limped to New York last year for the opening of the United Nations General Assembly, unable to generate sufficient domestic or international support for a military response to the Assad regime's use of chemical weapons within the deepening Syrian civil war.

He settled for a compromise that eliminated Syria's chemical weapon stocks, useful strategically but damaging to American credibility within the Middle East.

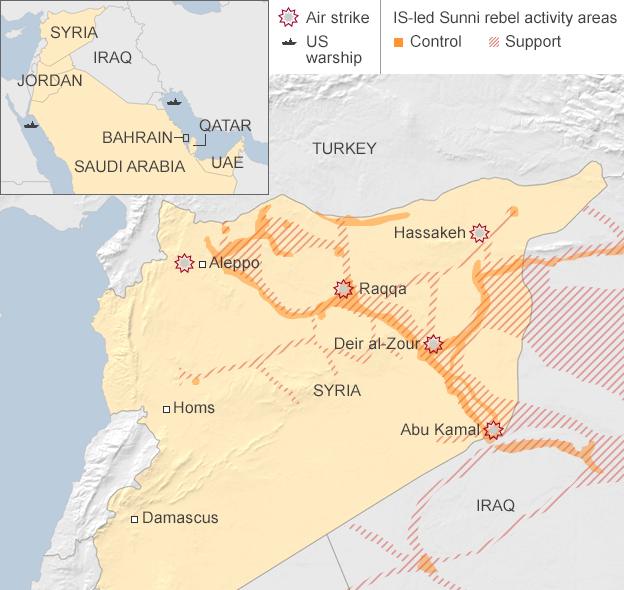

This week, Mr Obama provided a dramatic backdrop to the gathering of global leaders by launching military strikes against Islamic State (IS) and al Qaeda's Khorasan network in Syria, both of which are stronger and more threatening than they were a year ago.

The air strikes can certainly help to "degrade" extremist capabilities in Iraq and Syria, but by themselves will not be enough to "destroy" them, one of the stated objectives of the emerging campaign.

It remains to be seen how durable the international coalition is.

It now numbers more than 50 countries, but whether they can sustain military action over weeks and months is unclear.

F-18 fighters launched from the USS George HW Bush aircraft carrier in the Gulf

And since IS fields an insurgent force and not a formal army, finding meaningful targets to hit from the air will be a challenge.

Limiting the IS's ability to attract new recruits and access to financial resources are also pivotal. That will depend significantly on Turkey, which has not yet fully clarified what it will contribute to the effort.

Turkey's role was constrained by a large number of hostages that were recently freed, perhaps in exchange for the release of IS fighters.

In a sense, Mr Obama is putting together his Syria strategy one step at a time, addressing what he can even as he searches for a more comprehensive approach that may emerge over time, but is not available at the moment.

Islamic State's advance deep into Iraq in recent months, which threatened the future viability of both Iraq and Syria, forced a number of key players to reassess their priorities and policy options, beginning with Mr Obama himself.

Not long ago, the president declared there was no military solution to Syria that relies predominantly on the use of American hard power. But he is now willing to deploy military force to chip away at a dangerous byproduct of the Syrian civil war.

As the president said in anticipation of the strikes in Syria, "This isn't America versus Isil. This is the people of that region versus Isil. It's the world against Isil." (The White House uses another acronym for the group).

Everyone seems to be on board with the American approach, dealing with IS now and leaving questions about Bashar al-Assad for another day.

Interestingly, that seems to include Assad himself.

Prior to taking military action, Syria was warned not to interfere and the Assad government seems to have followed that advice.

Assad certainly welcomes the advent of "allies" willing to help him battle "terrorists" within his borders.

The significant involvement of Arab nations in the strikes will complicate the responses of Russia and China.

President Obama: ''We're going to do what's necessary to take the fight to this terrorist group''

China reflexively opposes any outside intervention in the affairs of a sovereign state.

Russia is all for eliminating violent Islamist extremists, and sees the Syrian regime as a necessary means of accomplishing that objective.

The fact that several major Sunni-majority countries, including Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar, took a prominent role in the strikes should enhance their perceived political legitimacy and will factor in both the international and regional response.

A year ago, Saudi Arabia declined a UN Security Council seat to protest major power paralysis regarding Syria. Riyadh has some significant energy cards that it can play against both Russia and China if they are overly critical.

Russia will likely encourage international action to remain focused on IS, but be fairly muted in its reaction.

How Middle East publics react will say a great deal about the viability of the emerging American strategy.

Since the struggle against IS is at its heart a civil war within Islam, if IS is to be destroyed as a viable political and religious entity, the most decisive front involves regional publics.

The fact that Iraq's Sunni population viewed Islamic State as the lesser of two evils when compared with the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad created the opening for IS's rapid advance across western and northern Iraq.

Until that calculation changes, there is little chance of defeating the Islamic State.

The defeat or destruction of IS remains a long-term challenge. That will depend on more effective action by Iraqi security forces and the Free Syrian Army, taking back territory from Islamic State on both sides of the border.

The former will take months, the latter years.

In the meantime, the air strikes should make IS's day-to-day existence more complicated. It has enjoyed a significant run of success in recent months while remaining mostly on the offensive.

Now it will have to defend itself on multiple fronts, a stern test for an actual state much less a virtual one.

PJ Crowley is a former Assistant Secretary of State and now a distinguished fellow at The George Washington University Institute of Public Diplomacy & Global Communication.