Mid-term elections: Is US foreign policy about to become more hawkish?

- Published

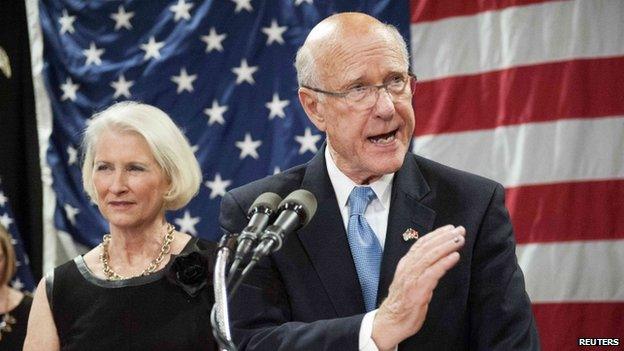

Republican Pat Roberts has questioned President Obama's response to IS

Barack Obama has tried to redefine the role the US plays in the world. But now that Republicans have won control of the Senate in the US mid-term elections, things are likely to change.

The president has adopted a scaled-back foreign policy. Known disparagingly as the "Analyst-in-Chief", he has emphasised international coalitions.

Above all he has been cautious - and tried to keep a small footprint abroad.

"Obama's basic instincts have been, 'Let's accommodate,'" says Colin Dueck, the author of a forthcoming book called The Obama Doctrine: American Grand Strategy Today.

"But there's a sense now among the average voter that things have spun a little out of control."

Less than a third of Americans approve of Mr Obama's foreign policy, external, according to a recent NBC/Wall Street Journal poll.

That is the lowest rating he has received on foreign policy in since he was elected president.

Republicans jumped on his unpopular approach, external to global affairs during their mid-term campaigns, saying Americans did not like the way he saw the world.

Now that Republicans have won - big time - and gained control of Congress, President Obama's foreign policy is in trouble.

For instance, he has said repeatedly he would like to close Guantanamo, but he's been blocked by members of Congress.

Kelly Ayotte, a Republican senator from New Hampshire, recently sent a letter to the White House, saying detainees should remain at the prison - and not be transferred elsewhere. Now Republicans are likely to become even more vocal about keeping detainees there.

The president has also worked on Iranian negotiations, hoping to convince Iran to limit its atomic activity. And he has imposed economic sanctions on Russia but shied away from a more direct confrontation with the Kremlin - though many Republicans on Capitol Hill have clamoured for one.

Conservative senators, such as Pat Roberts in Kansas, as well as Kentucky Senator Mitch McConnell, who will be the next Senate majority leader, reflect the view that President Obama has not taken charge in global hot spots, whether Syria, Ukraine or Iraq.

He has, for instance, used drones against militant groups to a greater degree than his predecessor, President George W Bush, since the un-manned aircraft allow the US to use force without endangering the lives of soldiers.

In 2011 President Obama authorised airstrikes on the forces of Col Muammar Gaddafi but said the US role in that country would be limited. He has also been ambivalent about airstrikes in Syria, though now the US is conducting strikes against Islamic State (IS).

President Ronald Reagan was involved in an arms control treaty with the Soviet Union in his last years in office

Many Republicans say he is too cautious, and they have waited long enough. More than a dozen members of Congress will meet him at the White House on Friday.

Administration officials say the president invited them to lunch because he hoped to work with them. "He wants to start right away looking for opportunities to co-operate," said White House spokesman Josh Earnest.

To that end, President Obama has softened some of his language. He has said in the past he could authorise a military campaign against IS without the approval of Congress.

At a press conference on Wednesday, though, he talked about the issue in a different manner. Now, he says, he will seek congressional authorisation. "The world needs to know we are united behind this effort," he said at the White House.

Republicans will soon become heads of Senate committees such as foreign relations and armed services. They are likely to start investigations and hold hearings on IS in Syria and other issues - and use their stewardship of these committees to send a strong message to the president about foreign policy.

"They can embarrass Obama administration officials and force them to testify," says Cato Institute's Christopher Preble, who's the co-editor of a book called A Dangerous World: Threat Perception and US National Security.

Wielding the majority in the Senate, Republicans such as John McCain of Arizona will try to force the president to act more decisively in international affairs - by sending ground troops to Syria, for instance, and by imposing harsher sanctions on Russia. Republicans will also raise tough questions about the Iranian negotiations.

Meanwhile, President Obama will bring in new foreign-policy advisers. Presidents frequently shuffle national-security staff during their years in the White House. The changes occur partly because advisers are exhausted from the work - and also because new staffers can deflect criticism of administration policies.

US President Barack Obama may be forced into increasing defence spending by Republicans

President Obama has acted in a conciliatory manner this week. Yet despite the clamouring of Republicans - and their new-found strength on Capitol Hill - Mr Obama will not dramatically change his philosophy about foreign policy.

In this way he's similar to other presidents. They have worked closely with Congress on domestic issues but often acted independently in foreign policy.

And like other presidents, he may try to reach diplomatic milestones during his last years in the White House.

"With Reagan it was the arms control treaty with the Soviet Union," says Mr Dueck. Yet Reagan had support for the treaty among members of Congress. That's not something President Obama can count on.

Still, he may try to achieve some of his foreign-policy goals without congressional approval. As Dueck says: "At the end of the day, the president is the commander-in-chief."

Obama will call the shots for two more years. But after that the US will have a new president - and will most likely play a more forthright role in places around the world, for better or worse.

Follow Tara McKelvey, external on Twitter.

- Published28 May 2014

- Published11 September 2014