Keystone XL pipeline: Why is it so disputed?

- Published

The Keystone XL pipeline has been disputed for more than a decade

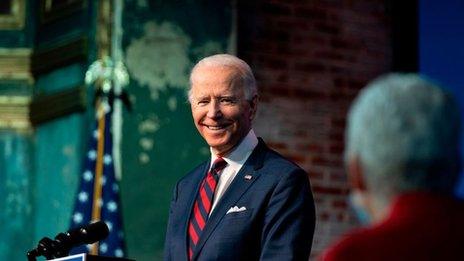

US President Joe Biden has cancelled permits for the controversial Keystone XL pipeline on his first day in office.

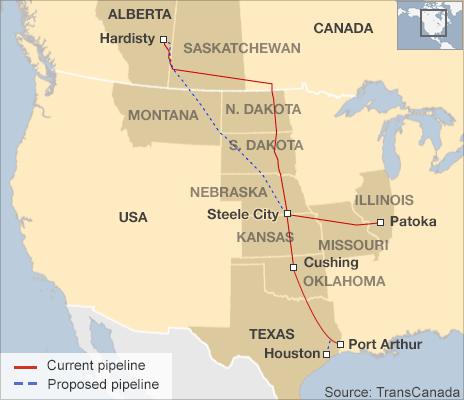

The pipeline had been projected to carry oil nearly 1,200 miles (1,900km) from the Canadian province of Alberta down to Nebraska, to join an existing pipeline.

Environmentalists and Native American groups have fought the project for more than a decade.

Development of the pipeline was blocked by the Obama administration in 2015, but President Trump overturned that order and allowed it go ahead.

What is Keystone XL?

A planned 1,179-mile (1,897km) pipeline running from the oil sands of Alberta, Canada, to Steele City, Nebraska, where it would join an existing pipe. It could carry 830,000 barrels of oil each day.

It would mirror an existing pipe, also called Keystone, but would take a more direct route, boosting the flow of oil from Canada.

A section running south from Cushing in Oklahoma to the Gulf of Mexico opened in January 2014. At the coast there are additional refineries and ports from which the oil can be exported.

The pipeline was set to be privately financed, with the cost of construction shared between TransCanada, an energy company based in Calgary, Alberta, and other oil shippers. US-produced oil would also be transported by Keystone XL, albeit in smaller quantities than Canadian.

Why did the US and Canada want XL?

Canada already sends 550,000 barrels of oil per day to the US via the existing Keystone pipeline. The oil fields in Alberta are landlocked and as they are further developed require means of access to international markets. Many of North America's oil refineries are based in the Gulf Coast, and industry groups on both sides of the border want to benefit.

An increased supply of oil from Canada would mean a decreased dependency on Middle Eastern supplies. According to market principles, increased availability of oil means lower prices for consumers.

Mr Trump said the project would create 28,000 construction jobs.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had also supported the pipeline and said "we are disappointed but acknowledge the president's decision" to cancel the permit to build it.

How was XL initially approved?

The Canadian National Energy Board approved the pipeline in March 2010 but Mr Trump's predecessor, Barack Obama, did not issue the presidential permit required in the US.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) advised him not to approve the pipeline.

Mr Obama said the project would not:

lower petrol prices

create long-term jobs

affect energy dependence

Donald Trump issued the permits within days of taking office, stipulating only that American steel be used in the work.

"We build it in the United States, we build the pipelines, we want to build the pipe," he said. "It's going to put a lot of workers, a lot of steelworkers back to work."

Why so much opposition?

Even back in 2011, the US state department appeared confused about the issue.

After first saying XL would not have significant adverse effects on the environment, it advised TransCanada to explore alternative routes in Nebraska because the Sandhills region was a fragile ecosystem.

Beyond the risks of spillage, the pipeline means a commitment to develop Alberta's oil sands.

The Keystone pipeline has long drawn the ire of environmentalists

Despite the recent push to find renewable sources of energy and move away from fossil fuels, the amount of oil produced in northern Alberta is projected to double by 2030.

It's argued by some that by developing the oil sands, fossil fuels will be readily available and the trend toward warming of the atmosphere won't be curbed.

The fate of the pipeline is therefore held up as symbolic of America's energy future.

In the here and now, more energy is required to extract oil from the Alberta oil sands than in traditional drilling, and Environment Canada says it has found industry chemicals seeping into ground water and the Athabasca River.

This risk to local communities is one of the reasons many have opposed the project.

First Nations groups in Northern Alberta have even gone so far as to sue the provincial and federal government for damages from 15 years of oil sands development they were not consulted on, including treaty-guaranteed rights to hunt, trap and fish on traditional lands.

Related topics

- Published19 February 2021