The silent enemy of Obama's migrant plans

- Published

Will undocumented people come forward amid uncertainty?

President Barack Obama is already facing strong and very vocal opposition in Congress to his recent immigration overhaul, but he will also have to confront a more silent enemy.

That enemy is the fear that many undocumented Hispanics have about presenting their personal information to the immigration authorities for a programme that could be reversed by a new administration in a matter of years.

"This deferred action is a temporary permit," says Claudia, who fled from violence in her native Mexico and has been living in the US since 2000.

"What is going to happen when Mr Obama is no longer president? They are going to know where I am, where my family is. Is it possible that we will all be deported?" she tells the BBC in El Paso, Texas.

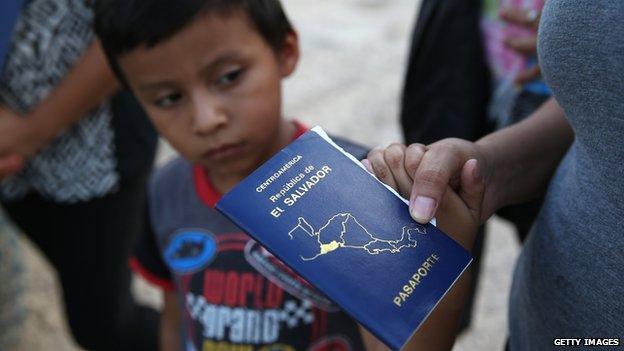

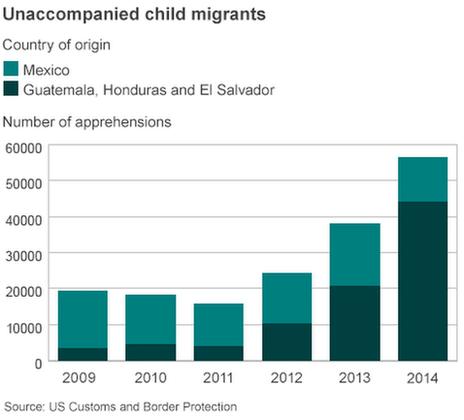

Over 50,000 unaccompanied children from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras were apprehended at the US-Mexico border last year

In November, President Obama announced a series of unilateral reforms that will allow about four million unauthorised immigrants to apply for provisional work permits, and for deportation proceedings to be deferred.

Claudia explains that she is eligible because she has been in the United States for nearly 15 years and has three sons who are married to American citizens, making them legal residents.

She says she plans to apply for relief, even though she is still very sceptical of the programme because it will not resolve her legal situation in the long term.

"With this announcement, there is no hope, you don't know where your future lies," she stresses.

"Before, you knew you were undocumented and you had to be on the lookout for the immigration authorities. But now you don't know, because you're going to say where you are and who you are, so it is even more uncertain."

Claudia's case is in marked contrast to the images of cheering and optimistic Hispanics shown in the media after the November announcement.

And her situation is far from unique. The White House has acknowledged that there is a challenge in trying to get people "out of the shadows", as president Obama likes to say.

'Keep calm, and wash your hands' - Immigrants are detained after being apprehended near the border

At a town hall meeting in Nashville, Tennessee, the president stressed the need to give people confidence so they can apply.

"The real question is, how do we make sure enough people register so it's not just a few people in a few pockets around the country," Mr Obama said.

"And that's going to require a lot of work by local agencies, by municipalities, by churches, by community organisations."

The president is interested in getting people registered because that is how the programme's success will ultimately be measured, but also because his previous decisions on immigration have faced similar challenges.

In 2012, Mr Obama announced the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) initiative, which allowed young adults who were brought to the US illegally as children to temporarily stay and work.

DACA was expanded as part of the November announcement, and it is seen as a blueprint for the more recent unilateral actions.

Both measures are limited in scope and in time, do not offer a pathway to citizenship, and were unveiled by President Obama without support by Congress.

Gang violence in Central America has driven migrants and their children north

Around 1.1 million unauthorised immigrants were thought to be immediately eligible for DACA, and slightly over 700,000 have had their applications accepted for review, according to data analysed by the Pew Research Center in December.

This means that nearly two-thirds of eligible candidates have submitted their personal information, but tens of thousands have not been able to change their status.

Many may be unaware of the programme, do not know they meet the criteria, or have had application problems. But it is the fear of deportation that may have played a role as well for those who have decided not to come forward.

Now, with the new executive action, the Obama administration hopes many immigrants will provide their personal details, and it is confident the initiative will not be overturned when a new president comes to the White House in 2017.

"Every time a US president has created a new immigration programme, it has been respected by other presidents," said Leon Rodriguez, the head of the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

"If you qualify for the deferred action programmes, this means you are not a priority for deportation," he added.

For undocumented Hispanics like Claudia, though, there is still deep uncertainty as the plan starts to be implemented and she prepares to present all her documents.

"There is fear, but this action is everything we have, it's all we can hold on to," she admits.

- Published21 November 2014

- Published21 November 2014

- Published30 September 2014

- Published24 April 2014