Viewpoint: Will US Congress scupper Iran deal?

- Published

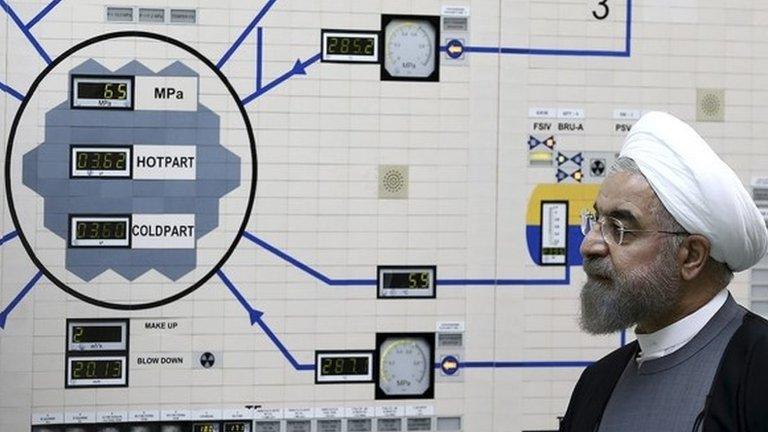

The "framework" of a future deal was announced by world leaders in Switzerland

The White House has achieved an apparent breakthrough and reached a framework agreement with Congress regarding oversight of a prospective nuclear deal with Iran.

After years of brinksmanship and an inability by both the executive and legislative branches to compromise absent self-inflicted crises, this is surprisingly close to the way America's deliberately divided government is supposed to work.

What is going on here?

A constructive combination of pragmatism and politics, although much like the ongoing negotiation with Iran, the oversight arrangement could be scuttled by opponents who may yet try to insert deal-breakers into the process.

First, the pragmatism.

Notwithstanding the remarkable shift in the American policy towards Cuba, which would otherwise be the foreign policy and domestic political story of the moment, a successful nuclear negotiation with Iran has been a key Obama priority since his first day in office.

Senator Bob Corker led congressional negotiations with the White House

A nuclear deal is unlikely to be as transformative as was envisioned six years ago - the increasingly violent transitions in Iraq, Syria, Libya and Yemen have eclipsed everything else in the Middle East.

And Iran, with its support of Assad and sub-state forces that seek to undermine the existing Sunni-dominated order, remains on the other side of this unfolding history.

But from President Barack Obama's standpoint, the intrusive inspections at the core of a nuclear deal reduce the risk of an Iranian breakout, an Israeli pre-emptive attack and a prospective regional nuclear arms race.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu opposed the deal in a speech to US lawmakers

That policy trifecta would rate justifiably high marks when considering Obama's foreign policy legacy.

While the administration continues to negotiate the complex details of an agreement with Iran, Obama rightly worried that Congress might add more sanctions or poison pills into the mix.

Strategically, if the P5+1/E3+3 process collapses, it should not be because of what the United States did, but what Iran was unwilling to do.

That said, scepticism of a prospective deal with Iran is bipartisan. With a clear majority of senators favouring a legislative role of some kind, Obama wisely relented and traded a limited and accelerated congressional review for certainty that it will remain on the sidelines until the negotiations end, one way or the other.

Iran bill is "a win", says senator who helped draft it

As to the politics, the performance of the new Republican-led Congress in its first 100 days has been less than stellar.

In the national security realm, Congress threatened to close down the Department of Homeland Security to protest Obama's immigration policies.

And a freshman senator, Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton, convinced 46 of his colleagues to sign a now infamous letter lecturing the Ayatollah about American constitutional procedure, which also called into question yet again America's willingness to abide by its international agreements.

Republicans needed to demonstrate an ability to govern more effectively and Senator Bob Corker of Tennessee, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee who notably did not sign the Cotton letter, skilfully negotiated the bipartisan compromise with the White House.

While there has been much huffing and puffing about the emerging deal, and pledges of support for Israel, it's unlikely Congress will either block it or override a presidential veto if they did.

For one thing, it's hard to get 60 or 67 senators to agree on the time of day at the moment. For another, if they scuttled the deal, they would be responsible for what happens next.

Hillary Clinton will be asked about Iran during her presidential campaign

The Republican strategy is to let Obama own the nuclear deal and then run against it in the presidential campaign now under way. Three of the 47 senatorial signees have already announced their candidacies.

If a deal is reached with Iran - still likely but hardly a certainty - it will take 6-12 months to implement. That means the first executive waivers on sanctions will come right as the presidential race heats up.

Defending the deal and the engagement policy behind it will then be not just Obama's challenge, but Hillary Clinton's as well, an interesting twist on a question that dominated the 2008 campaign and will again in 2016.

P.J. Crowley is a former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State and now a professor of practice and fellow at The George Washington University Institute of Public Diplomacy & Global Communication.

- Published14 July 2015

- Published30 March 2015