Ronald Reagan shooting: John Hinckley back in court

- Published

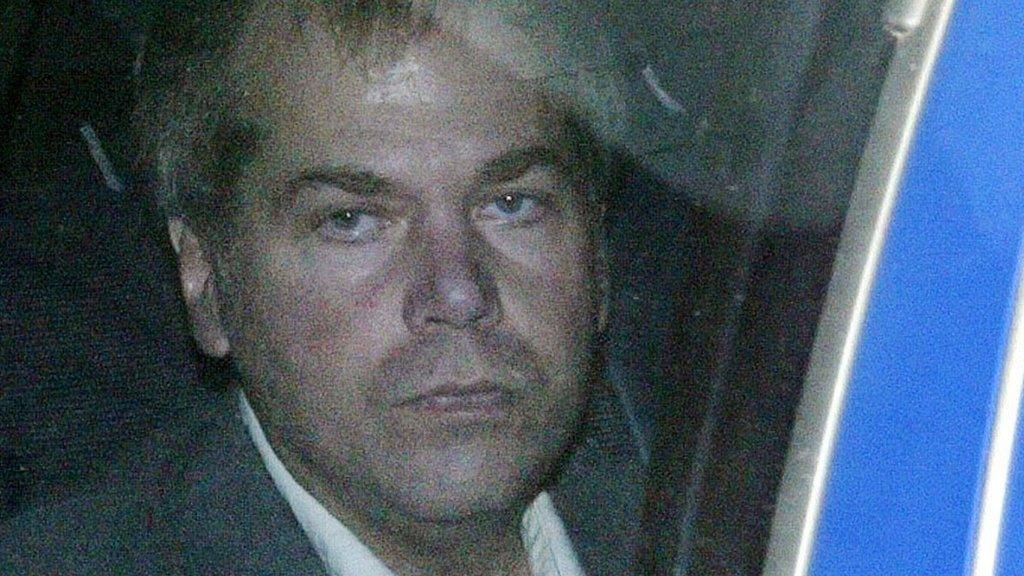

John Hinckley Jr, shown here in 2003, lives at a psychiatric facility in Washington

John Hinckley Jr leaves a psychiatric hospital to see his mum for regular visits. Now he wants to leave the place entirely, raising questions about how society should re-integrate those who've been deemed insane.

John Hinckley Jr, the man who shot President Ronald Reagan and was found not guilty by reason of insanity, looks as if he's got some sun.

On a bright, sunny Tuesday, he attended an evidentiary hearing before Judge Paul Friedman of Federal District Court in Washington.

At 59, Mr Hinckley walks slowly and wears thick-soled shoes. Yet he still has a baby face. His ruddy skin is smooth and unblemished except for a mole below his ear.

Mr Friedman will decide soon whether or not he remains at St Elizabeths Hospital, a psychiatric facility in Washington, or moves out.

Mr Hinckley smiles slightly at a joke that Mr Friedman, who has a light touch, made during the hearing. Mr Hinckley seems comfortable in the courtroom, which is perhaps unsurprising given the amount of time he's spent in one.

His lawyer, Barry Levine, says he's changed dramatically since the assassination attempt and no longer needs to be held at St Elizabeths. "There's no evidence that he would be dangerous," says Mr Levine. "The risk is low."

Yet prosecutor Colleen Kennedy says he must be watched: "He's committed a horrific crime, shooting four people."

Besides the wounded Mr Reagan, his victims were Thomas Delahanty, a police officer; Timothy McCarthy, a US Secret Service agent; and James Brady, the former White House press secretary.

All survived the shootings, but Mr Brady was paralysed. He died in 2014 aged 73, and authorities declared his death a homicide.

James Brady, shown three years before his death in 2014, was also shot in the assassination attempt

"We know Mr Hinckley has been extremely violent in the past," Ms Kennedy says. "He is still mentally ill."

At the heart of the matter is whether or not someone who's been deemed clinically insane can safely return to society. The decision is fraught with peril.

In Canada a schizophrenic man, Vince Li, stabbed and killed another passenger, Tim McLean, on a bus in 2008.

Mr Li has recently been granted permission to leave a psychiatric institution where he's been held - and move into a group home.

Family members of Mr McLean and others have protested, saying they don't think it's safe for Mr Li to leave the psychiatric institution.

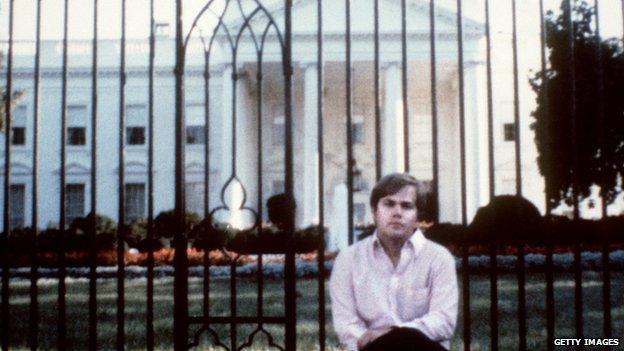

John Hinckley Jr, shown here at the White House, wrote to Jodie Foster before he shot the president

The insanity plea has a long history, says Charles Ewing, a University at Buffalo Law School professor and author of Insanity: Murder, Madness and the Law.

"You should not punish someone who's committed a crime while they're insane," he says. "That goes back to early Roman law."

Yet the law also states they can go free when they're better.

Mr Hinckley visits his mother in Williamsburg, Virginia, spending 17 days a month there. He goes to see his friends and hangs out at bookstores.

"Ordinarily when someone gets to this point, it's a very difficult to say they're a continued danger," says Mr Ewing.

"It seems like this is a political issue more than a psychological issue," he says. "Because of the nature of his offence, people don't feel like he should ever be released."

Mr Friedman looks over at Mr Hinckley during the hearing. For most of the morning he seems docile and almost childlike.

He slumps in his chair and taps his foot as Mr Levine talks about how normal - and unthreatening - he is. (Even Mr Friedman looks bored. He leans his head back and looks up at the ceiling.)

Deon Merene, a deputy general counsel at St Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, says Mr Hinckley poses no danger: "He has a long record of being very compliant."

After trying to kill President Reagan, John W Hinckley Jr was placed in St Elizabeths hospital

In these cases, says Mr Ewing, judges must consider individual circumstances and philosophical questions: "Basically it comes down to a question of which do we value more - an individual's freedom or our safety."

Mr Friedman has wrestled with the case for years - and has long known he'd have to make a decision about whether or not to release Mr Hinckley. He will make a choice some time soon.

"I knew this day would come, but it doesn't make the decision any easier," Mr Friedman says at the end of the hearing, adding with a smile: "That's why I get paid the big bucks."

Follow Tara McKelvey, external on Twitter.

- Published30 March 2011

- Published22 April 2015