Is the death penalty dying out in the US?

- Published

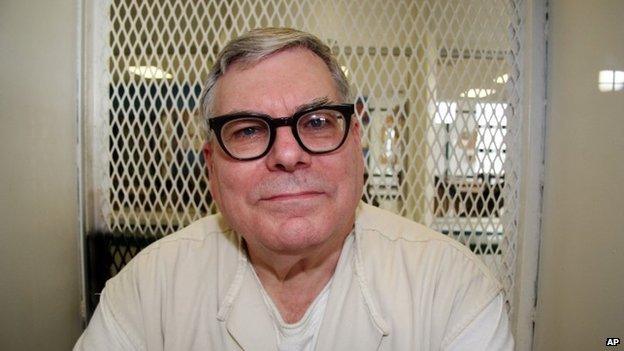

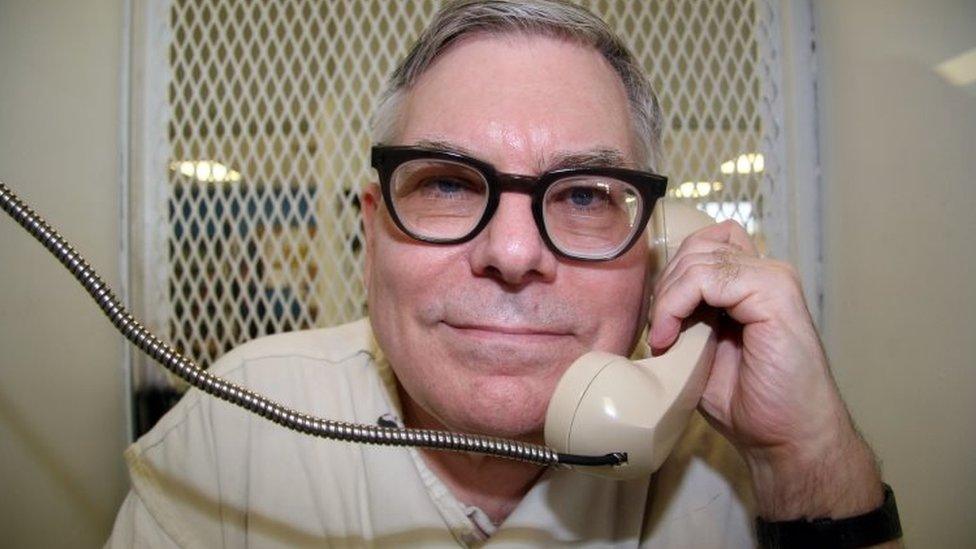

Lester Bower Jr was the eighth man put to death by lethal injection in Texas this year

The US state of Texas executed Lester Bower Jr by lethal injection last week. At 67, he was the oldest prisoner Texas put to death in decades.

Convicted of killing four men, Bower was granted six stays of execution during more than 30 years on death row. He maintained his innocence to the end.

Since the death penalty was reinstated by the Supreme Court in 1976 after a brief lull, Texas has executed nearly five times as many prisoners as Oklahoma or Virginia, the two states with the next highest execution rates.

But since European pharmaceutical companies started refusing to sell the drugs used for lethal injections, external to US states, things have been changing, even in Texas.

"We may well see the end of the death penalty in the next 20 years," Robert Dunham from the Death Penalty Information Center told Newshour Extra.

"We're seeing it happen one by one, state by state, and even in the states that do have it we're seeing it pursued less frequently and imposed even less frequently than that."

'Unworkable and unfair'

Recently Nebraska became the latest state to abolish the death penalty. Legislators narrowly voted to overturn the governor's veto.

Campaigners point to the fact that this happened in a traditionally conservative state as evidence of a wider shift in public opinion - across the country.

"As the public sees more and more that this system is unworkable and unfair and that it doesn't enhance public safety, the policymakers are abandoning it," said Diann Rust-Tierney, executive director of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty.

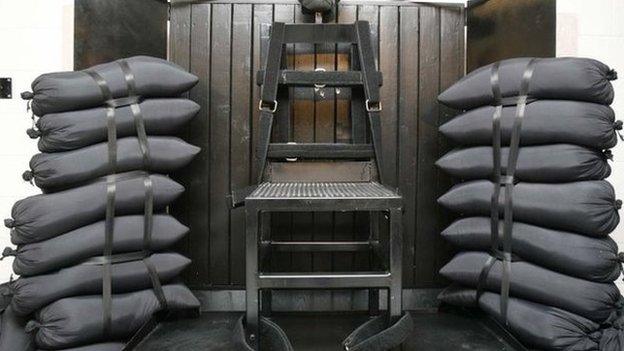

Lethal injection is the most prevalent form of execution in the US

Capital punishment in the US

The death penalty is a legal punishment in 31 US states

Since 1976 Texas has carried out the most executions (526), followed by Oklahoma (112) and Virginia (110)

At the beginning of 2015, there were 3,019 inmates on death row in the US, of whom 56 were women

California has the most prisoners on death row, 743, but has carried out only 13 executions since 1976

But is Europe's embargo on selling the lethal drugs changing American hearts, or merely changing execution methods?

Oklahoma recently approved the use of the nitrogen gas chamber, external, while Utah has reinstated the use of the firing squad.

Paul Ray, a Republican member of the Utah House of Representatives, argues in favour of the move: "We're not playing God, we are just carrying out what the law of the land states we do. You have to make sure the people on death row are the guilty ones, but it's justice."

'Botched' executions

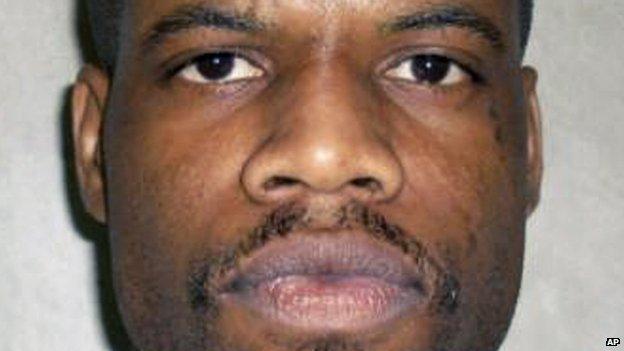

Clayton Lockett is reported to have tried to sit up and speak after being given a lethal cocktail of drugs in April 2014

Lethal injection became the preferred method of execution in the 1980s. It was seen as a humane, clean, safe way to dispatch the men (they are mostly men) convicted of the very worst crimes.

There are no unpleasant side-effects, such as blood as in the case of firing squad, or the smell of burning flesh associated with the electric chair and fewer safety issues for the executioners as with the use of the gas chamber.

But the scarcity of the usual drugs used for lethal injections has led states to improvise with other cocktails, sometimes with distressing results.

A number of high-profile, so-called "botched" executions hit the headlines last year, including the case of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma. He took more than 40 minutes to die, eventually of a heart attack.

Witnesses described him writhing in agony and gasping for air. Shocking for those who saw the execution, but others were quick to remind the public that Lockett was convicted of rape and murder, and even of burying one of his victims alive.

As a result of these botched executions, the Supreme Court is currently considering if the use of the available drugs contravenes the Eighth Amendment of the US Constitution, which forbids "cruel and unusual punishments".

Executioner's conscience

But the process of taking a life does have an impact on those tasked with the job.

Dr Allen Ault is now dean of the college of Justice and Safety at Eastern Kentucky University, but in the 1990s he served as the corrections commissioner for the state of Georgia and as such personally carried out five executions himself, an experience that still haunts him.

"I have a conscience about it, when you actually do it, it feels like murder," he explains. "I know many people who've participated in executions who have been destroyed by it. Some have committed suicide, many have turned to drugs and alcohol."

Debra Milke spent more than two decades on death row for the alleged killing of her four-year-old son, before having her conviction overturned in 2013

Robert Blecker is professor of law at New York Law School, and author of the book, The Death of Punishment. He argues that the weight of public opinion is still in favour of capital punishment but that the "liberal elite" has hijacked the debate and interpret the opinion polls to suit their cause.

"The media loves to spin it. If you take an honest poll of the people you will see overwhelming support for the death penalty, not the elites, but the people. We have a responsibility for justice, we have a responsibility to punish proportionately."

Wrongful convictions

While many Americans may support the use of the death penalty in principle, there are concerns that the legal system has its flaws - sometimes convicting the wrong people.

Debra Milke served 22 years on death row in Arizona - her conviction was thrown out in 2013 and attempts to bring a retrial were dismissed in March this year, external.

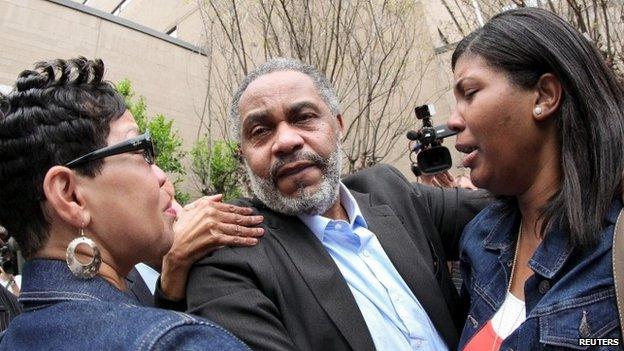

Anthony Ray Hinton served nearly 30 years in Alabama, before being freed this year.

Anthony Ray Hinton was freed in April this year, after nearly 30 years on death row

Jennifer Thompson told Newshour Extra that after surviving a rape at knife point, she mistakenly identified the wrong man as her attacker. Having previously supported the death penalty she has since changed her mind.

"Had it been 10 years prior he would have received the death penalty," she says, but when DNA evidence proved he was not her attacker she said she felt "deep grief and shame for contributing to an innocent man going to prison for something he hadn't done. If there is a chance that someone could be innocent I can't be in favour of a punishment that is so final."

The shortage of drugs used to dispatch prisoners on death row is forcing a re-examination of the American conscience. The Supreme Court's decision on the lethal injection is expected later this month.

But for many, although the alternatives to the lethal injection are unpleasant, even messy, the sense that justice means "a life for a life" prevails as a compelling argument.

For more on this story, listen to Newshour Extra on the BBC iPlayer or download the podcast.

- Published4 June 2015

- Published28 May 2015

- Published11 May 2015

- Published23 March 2015