Why is the US Supreme Court reviewing the lethal injection?

- Published

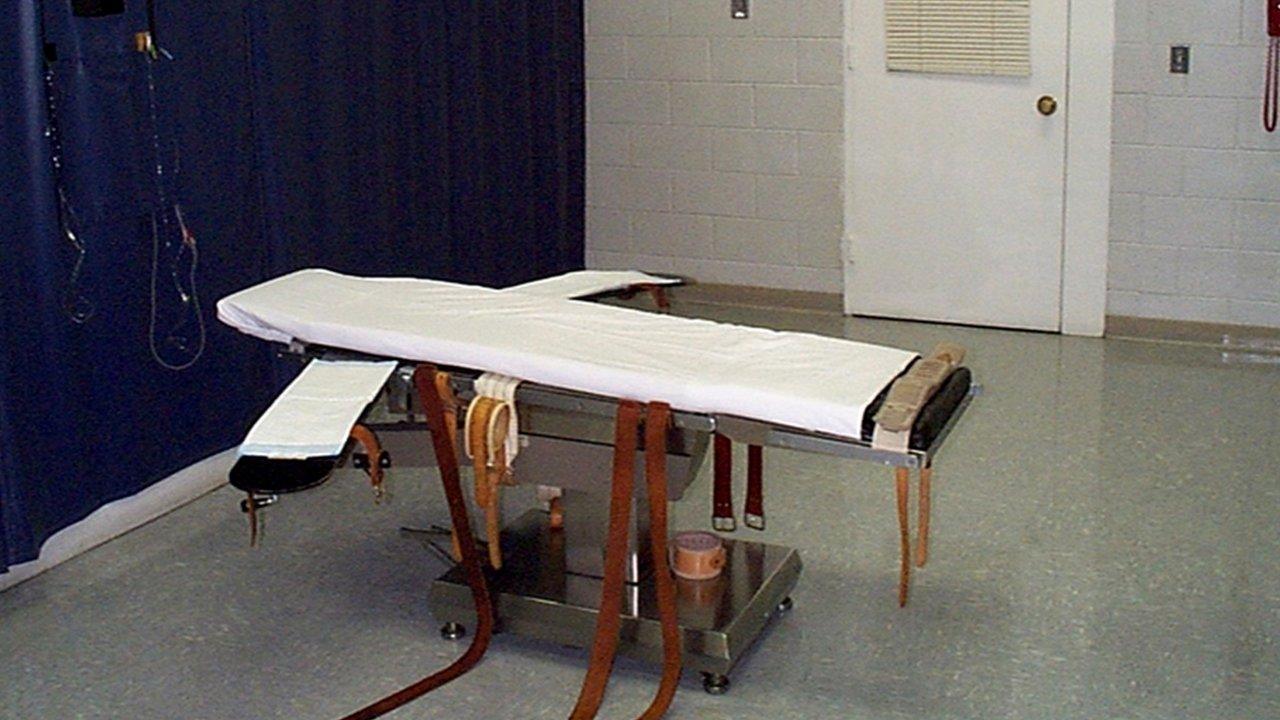

Lethal injection is the most prevalent form of execution in the US

The United States' Supreme Court has recently heard oral arguments in a death penalty case called Glossip v Gross, external, concerning the use of lethal injections when putting prisoners to death.

Whichever way the Court rules, its decision will have significant ramifications for the way in which capital punishment is carried out.

What is the issue in Glossip v Gross?

The Eighth Amendment to the US Constitution forbids "cruel and unusual punishments", and ever since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976, external, states have tried to use methods of execution that are as humane as possible.

For many years, states have relied on lethal injections because these are considered to cause less pain and suffering than other methods, such as hanging, electrocution and gassing.

In this case, though, three inmates in Oklahoma have argued that the current combination of drugs that are used in lethal injections in Oklahoma poses a risk of severe pain and suffering, contrary to the Eighth Amendment.

Why haven't death row inmates argued this point before?

They have. In 2008, in Baze v Rees, the Court upheld the lawfulness of Kentucky's lethal injection procedure, which was substantially similar to the procedures used in other death penalty states.

Capital punishment in the US

The five ways the US executes - in 45 secs

The death penalty is a legal punishment in 32 US states with Texas having carried out the most executions; Connecticut and New Mexico have abolished the death penalty but their laws were not retroactive and both states still have prisoners on death row

Eighteen US states have abolished the death penalty, the last was Maryland in 2013

California has the most prisoners on death row, at more than 740

In March 2015 Utah resumed the use of firing squads for executions

A study by four Seattle University professors, external looking at the costs of the death penalty in Washington found that a case costs $1.15m (£750,000) more to prosecute than a similar case where the death penalty was not sought

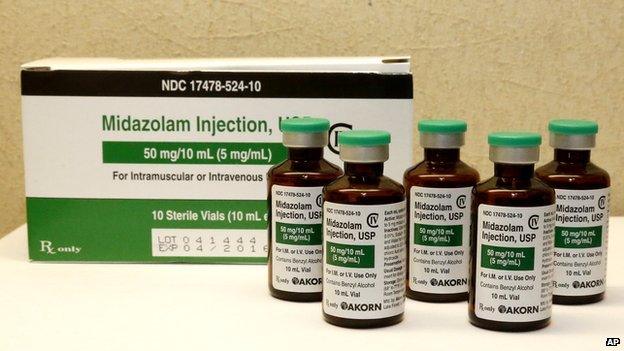

Midazolam was developed in the 1970s as a sedative

Why is this issue being heard again?

Much has changed since 2008. At that time, states across the US used a combination of three drugs to put inmates to death.

The first was sodium thiopental, which acted as an anaesthetic. Once the inmate had lost consciousness, they would be injected with pancuronium bromide, which would paralyse the prisoner. The third drug to be administered was typically potassium chloride, which would stop the prisoner's heart and kill them.

Since 2010, though, states have found it increasingly difficult to acquire the drugs needed for lethal injections, particularly the first drug, sodium thiopental.

Pharmaceutical companies have stopped supplying drugs, external, on the basis that they do not want to be complicit in the taking of life.

State authorities have therefore acquired the drugs needed through back-channels and dubious avenues - in some cases, the drugs were sourced from the back offices of a driving school based in a west London suburb, external.

In Oklahoma, and in three other states (Florida, Ohio and Arizona), a three-drug cocktail is still used, but instead of sodium thiopental, a drug called midazolam is used. It's been argued that midazolam is ineffective as an anaesthetic, and that people therefore feel the pain that is caused by the other two drugs.

What evidence has been presented to the Court?

Four of the Justices on the US Supreme Court have expressed dismay with the lack of scientific evidence that has been offered by the state to defend its protocol.

On the other hand, the prisoners have raised the spectre of "botched" executions, external to provide evidence that the current protocol creates a risk of severe pain and suffering.

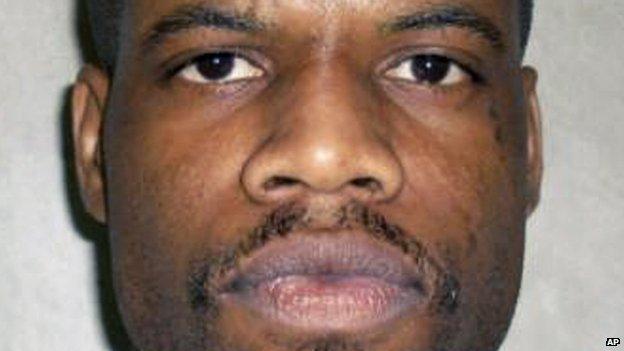

In 2014, three prisoners who were put to death with a cocktail involving midazolam appeared to regain consciousness before the lethal injection process was completed, and witnesses reported that the men involved were gasping for air, and writhing about in pain.

Clayton Lockett is reported to have tried to sit up and speak after being given a lethal cocktail of drugs in April 2014

They have also pointed out that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has refused to classify midazolam as an anaesthetic because they are not convinced that it works as intended.

What will happen if the Court concludes that current protocols are ok?

In the short term, it will mean that executions in the four states concerned will proceed as normal.

In the long term, though, and depending on the reasoning of the Court, it might mean that states across America are given carte blanche to experiment with various combinations of drugs, and the courts won't interfere with their processes.

What will happen if the Court rules that this method is unacceptable?

Although death penalty abolitionists will hope that this will be another nail in the coffin of capital punishment, experience suggests otherwise.

States that have struggled to acquire the drugs needed for lethal injection have not given up on capital punishment, and have instead reintroduced other means of killing people.

In April, Oklahoma passed a law that would allow the use of nitrogen gas, external to kill inmates, in the event that lethal injections are no longer possible. In March, Utah introduced a law that permits the use of firing squads in the event that lethal injections are no longer possible.

Despite making the use of firing squads legal, Utah Governor Gary Herbert admitted he still found the method "a little bit gruesome"

Is there any way of predicting the Court's decision?

At oral arguments, some of the Justices used language that indicated which way they were leaning.

Justice Sotomayor repeatedly referred to the idea that, without proper anaesthetic, death by lethal injection was equivalent to "burning someone alive". She seems to be of the view that such a method of execution is barbaric.

Justice Alito, on the other hand, suggested that the blame for faulty lethal injections lay at the door of death penalty abolitionists, since it was the anti-death penalty movement that persuaded pharmaceutical companies to stop trading in drugs.

According to Alito, abolitionists have waged "a guerrilla war against the death penalty, which consists of efforts to make it impossible for the states to obtain drugs that could be used to carry out capital punishment with little, if any, pain".

It's probably safe to predict that the four liberal Justices will vote against the current lethal injection protocol, and the four conservative Justices will vote to uphold the current procedure.

The outcome will likely depend on how Justice Kennedy will vote. Kennedy is usually classified as a conservative, but occasionally votes with the liberal bloc. We'll find out in June.

Justice Anthony Kennedy - the key vote?

Are there any other features of this case that we should know about?

When the Court agreed to hear this case, there were actually four prisoners involved. However, one of these inmates - Charles Warner, external - was executed shortly after the Court agreed to hear the case because of a procedural oddity.

Procedurally, the Court will only hear a case if four of the nine Justices agree to hear it. However, the votes of five Justices are needed in order to stop an execution.

Although four Justices agreed to hear the case, this was not enough to stop Warner being put to death. It's arguable that Warner should have had his execution postponed while the Justices considered the issue.

Dr Bharat Malkani researches and teaches in the fields of human rights and criminal justice, with a particular focus on the death penalty. He is the co-ordinator of Birmingham Law School's Pro Bono Group at the University of Birmingham.

He has written about executions for The Conversation, external.

- Published4 May 2015

- Published29 April 2015

- Published30 April 2014

- Published8 March 2012

- Published8 August 2012