Terrorism v hate crime: How US courts decide

- Published

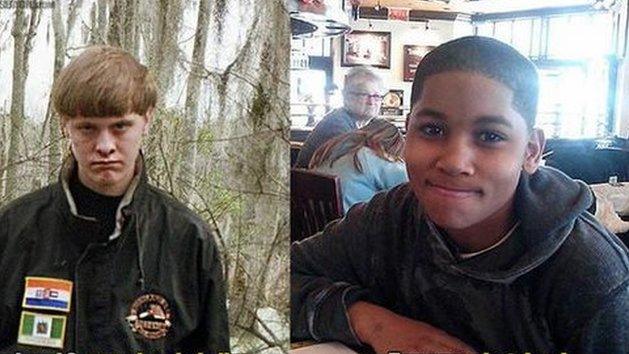

Dylann Roof will not face state-level hate crime charges

After the murder of nine black Americans at a church in Charleston, South Carolina by a white man, advocates and commentators are calling for suspect Dylann Roof to be described as a terrorist.

Roof has been charged with nine counts of murder. South Carolina has no hate crimes statute, and so it will be not be part of the state's prosecution. But the US Department of Justice has opened up a separate investigation, and it is possible Roof could also face federal charges.

On Friday, a spokeswoman for the justice department said the crime was "undoubtedly designed to strike fear and terror into this community, and the department is looking at this crime from all angles, including as a hate crime and as an act of domestic terrorism".

Who gets called a terrorist by the media and politicians can be a matter of semantics and speculation.

Legally, there are some guidelines for who gets charged with terrorism - and also some room for interpretation.

What is the legal difference between hate crimes and terrorism in the US?

Hate crimes are not separate charges, but an "enhancement" to an existing charge, like assault or murder. Prosecutors use this option to increase the severity of the punishment for those crimes - a potential sentence for a hate crime assault would be higher than an assault with no hate crime enhancement.

In the US, a hate crime is generally defined as "motivated in whole or in part by an offender's bias against a race, religion, disability, ethnic origin or sexual orientation".

Many - but not all - US states have their own hate crime statutes that apply to charges prosecuted under state laws.

Terrorism charges are discrete offences, including charges like material support for terrorist groups and use of weapons of mass destruction.

The US defines "domestic terrorism" as activities that meet three criteria - "dangerous to human life that violate federal or state law", are intended to intimidate or coerce civilians or governments, and occurs primarily within the US.

But "different parts of the US government tend to have different definitions", says Gary LaFree, director of National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (Start).

The FBI and the Bureau of Prisons cannot even agree on the number of prisoners currently incarcerated on terrorism charges, he adds.

What gets charged as terrorism in the US?

The decision to bring terrorism-related charges or add a hate crimes charge rests with the prosecutor.

Heidi Beirich, director of the Southern Poverty Law Center's Intelligence Project, says if prosecutors feel evidence against a suspect is already solid then adding hate crime charges may be an unnecessary complication to the case. The incentive is especially strong in capital murder cases, where there is no higher penalty to give.

Many of the most successful US terrorism prosecutions have been against suspects prosecuted for support or actions for overseas groups like al-Qaeda and Islamic State.

Domestic organisations and individuals, especially neo-Nazi and white supremacists, tend to be charged with conspiracy, organised crime and weapons violations, Beirich says.

Roof allegedly killed nine people who were attending bible study at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church

An attempt to bomb a Martin Luther King Jr Day parade in Spokane in 2011 was initially described as a "domestic terrorism incident", according to the Congressional Research Service.

The perpetrator later pleaded guilty to attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction and federal hate crimes. Afterwards the FBI said a "horrific hate crime" had been prevented, but the terrorism language was gone.

Terrorism prosecutions are harder to prove than regular crimes, Dr LaFree says, in part because the crucial parts of the charges rely on motive and other psychological factors.

"A relatively small number of cases of those that could be classified as terrorism are actually prosecuted as terrorism," he says, adding a study of Justice Department cases that went forward with terror charges had a lower rate of conviction than those that didn't.

- Published19 June 2015

- Published19 February 2015