Who is Martin Shkreli - 'the most hated man in America'?

- Published

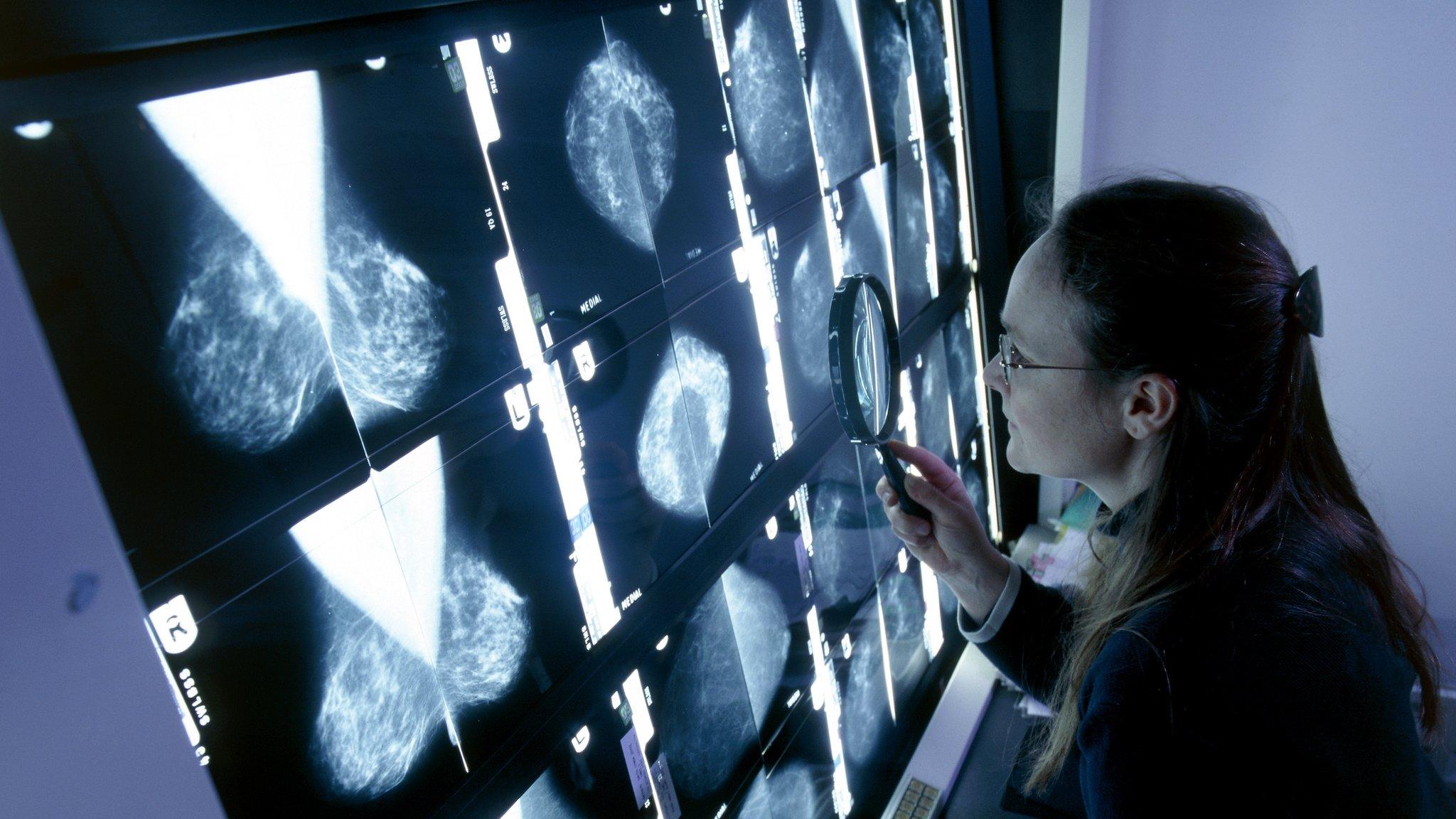

Turing Pharmaceuticals boss Martin Shkreli had previously defended the price raise

Judging by social media, Martin Shkreli, the 32-year-old chief executive of Turing Pharmaceuticals, may be the most hated man in America right now.

He's been called a "morally bankrupt sociopath", a "scumbag" a "garbage monster" and "everything that is wrong with capitalism." And those are some of the tamer comments.

So how did a rap music-loving, former hedge fund manager suddenly become the target of online ridicule and even death threats?

His company recently acquired the rights to Daraprim. Developed in the 1950s, the drug is the best treatment for a relatively rare parasitic infection called toxoplasmosis. People with weakened immune systems, such as Aids patients, have come to rely on the drug, which until recently cost about $13.50 (£8.80) a dose.

But Mr Shkreli announced he was raising the price to $750 a pill. The more than 5,000% increase and his brash defence of the decision has made him a pariah among patients-rights groups, politicians and hundreds of Twitter users.

Other drugs companies have made similar moves raising the price of niche products, but few have so publicly and so unapologetically answered critics.

The backlash became so pitched on Tuesday that Mr Shkreli agreed to lower the price of Daraprim to an "affordable level".

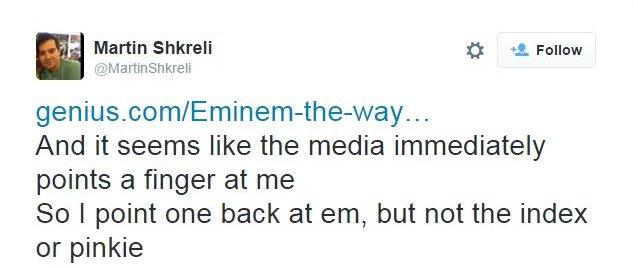

Martin Shkreli, seen here in an August Twitter post, has aggressively answered critics

Humble beginnings

Martin Shkreli, the son of Albanian and Croatian immigrants, grew up in a working-class community in Brooklyn, New York. He skipped several grades in school and received a degree in business from New York's Baruch College in 2004.

At 17, he began his first internship at Cramer Berkowitz & Co, the hedge fund founded by television personality Jim Cramer.

In 2006, Mr Shkreli started his own hedge fund, Elea Capital Management.

The fund closed a year later after a $2.3m lawsuit from Lehman Brothers, which collapsed before it could collect on the ruling.

After Elea, Mr Shkreli started MSMB Capital Management in 2008. The fund would be his launch pad for founding biotech firms including Turing.

Shkreli moved into the pharmaceutical industry after working as a hedge fund manager

A rocky start in pharmaceuticals

Turing was not Mr Shkreli's first foray into the pharmaceutical industry. In 2011, he founded biotech firm Retrophin, with the goal of focusing on medicines for rare diseases.

He was ousted as head of the company in 2014 amidst allegations he improperly handled legal settlements.

A year later the company filed a $65m lawsuit that claimed Mr Shkreli created Retrophin and took it public simply to pay off investors in his old hedge fund, MSMB when the fund went under.

Mr Shkreli has denied the accusations. "They are sort of concocting this wild and crazy and unlikely story to swindle me out of the money," he told the New York Times.

On August 4, 2017, a jury found Mr Shkreli guilty of three of eight counts, including securities fraud, in a criminal case brought by US prosecutors. But they cleared him of allegations that he had looted Retrophin to make payments for the hedge funds. The civil suit brought by Retrophin remained pending as of 4 August.

Turing Pharmaceuticals bought the rights to Daraprim in August

A second chance

Turing Pharmaceuticals was launched in February 2015 after Mr Shkreli was forced out of Retrophin.

The business claims its goal is to focus on treatments for serious diseases for which there are limited options. "We are dedicated to helping patients, who often have no effective treatment options," a statement on Turing's website said.

The company only has two products on the market Daraprim and Vecamyl, which treats hypertension.

Mr Shkreli has argued the Daraprim price increase was warranted because the drug is highly specialised; he likened the Daraprim to an Aston Martin previously being sold at the price of a bicycle. The additional profits he said will be used to make improvements to the 62-year-old drug recipe.

One of Shkreli's first tweets about the Dramaprim controversy

Mr Shkreli did not take the criticism of his company's actions lightly.

On Sunday, he sent out a hostile tweet accusing the media of singling him out. "And it seems like the media immediately points a finger at me. So I point one back at em, but not the index or pinkie," he wrote, quoting an Eminem song.

His tone later softened following several TV interviews where he claimed the profits of the drug would be used to create a better product.

All of the negative attention may have finally had an effect on Mr Shkreli.

His Twitter account, which had sparred with critics for days, went dark and then Mr Shkreli agreed to lower the price.

"We've agreed to lower the price on Daraprim to a point that is more affordable and is able to allow the company to make a profit, but a very small profit," he told ABC News. "We think these changes will be welcomed."

- Published22 September 2015

- Published7 August 2014