Robin Wright: A movie star and a maths expert fight for equal pay

- Published

House of Cards star Robin Wright has revealed she demanded the same pay as her co-star Kevin Spacey - but what does fighting for equal wages look like for women who are not movie stars?

She plays a no-nonsense character in House of Cards, and in real life Robin Wright is no different.

For four seasons, viewers have seen her in the role of Claire Underwood, the Machiavellian partner of stop-at-nothing politician, Frank Underwood, played by Kevin Spacey.

Both actors have also directed and produced episodes of the show. But while their roles are equally prominent, for years their salaries were not in parity.

"I was like, 'I want to be paid the same as Kevin.' It was a perfect paradigm and example to use, because there are very few films or TV shows where the male—the patriarch and the matriarch are equal. And they are in House of Cards," she told an audience at New York's Rockefeller Foundation.

Wright looked at statistics which showed that for some time, her character was more popular than Spacey's.

"So I capitalised on it. I was like, 'You better pay me or I'm going to go public…and they did.'"

Robin Wright talks about fighting for equal pay

Wright's success at equalising her pay is a story to be noted, because it is still incredibly rare.

"She is playing a popular and important character in a series. She has leverage and she used it," says Lisa Maatz, vice president for government relations at the American Association of University Women (AAUW), which has conducted research into the broader issue.

"I admire her for standing up to them. Not everybody is going to be as fortunate. But her situation in terms of being underpaid is far too common."

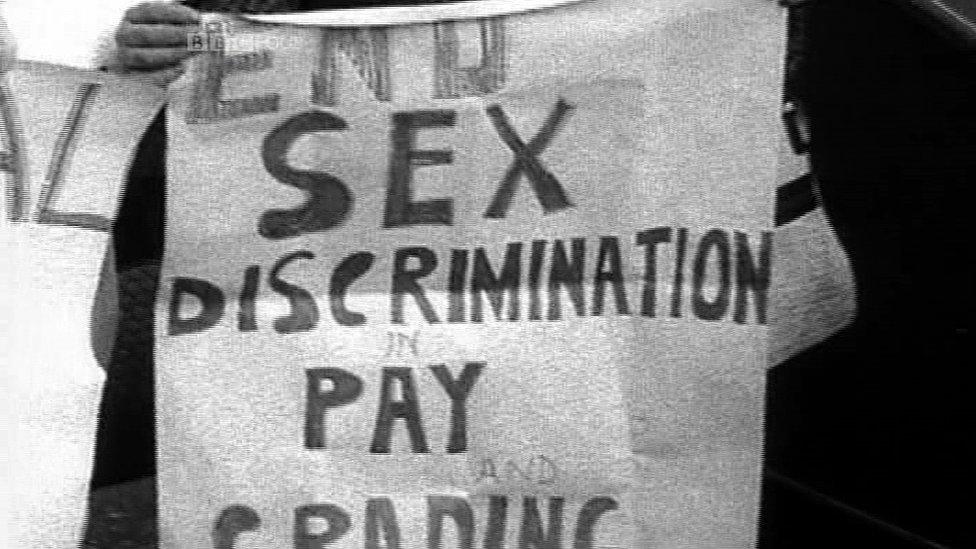

Parity is this year's theme for International Women's Day so 46 years after the introduction of the Equal Pay Act, BBC Rewind looks back on the history of the gender pay gap.

US government statistics show that on average, women are paid less than their male counterparts, 79 cents for every dollar a man earns.

According to the White House, the median wage of a woman working full-time all year in America is about $39,600 (£27,116), 79% of a man's median earnings, which stand at $50,400.

The statistic is widely used to illustrate the discrepancy in pay across the sexes, and looks across all sectors.

In Fresno, California, Aileen Rizo took a similar stand against her employer after she learned she was receiving less pay than a new male employee, who didn't have a masters degree like she did.

Ms Rizo had been working as a maths consultant for four years for Fresno County Office of Education, when she found out that the new hire was being paid at the highest salary scale (a nine), while she was being paid at the lowest (a one).

Aileen Rizo brought a complaint against unequal wages

When she confronted her human resources department about the difference, she was told it wasn't a mistake. "They said they'd used my prior pay as a guide, and that's why I was on less," she explained.

Ms Rizo began legal action against her employers in 2013, who argued they set wages based on the employee's most recent salary, plus a five percent increase. Experience wasn't a determining factor, they said.

Representatives for Fresno County pointed out that a woman working in the same department as Ms Rizo, was being paid more, and said that in the past 25 years more women had been on higher salary scales, than men in the same or similar position in the department.

The court ruled in Ms Rizo's favour, arguing that the fact another woman earned more than her, shouldn't diminish her right to a fair wage. Her employers appealed the decision, and the case is still ongoing.

Since she began her lawsuit, Ms Rizo is now receiving the same pay as her male colleague, but she continues to fight for backdated wages. She also testified before the California legislature, which has since passed an Equal Pay Act in the state.

While she believes employers need to be more transparent and fair, she does also think women could also do more.

"We do need to get better at negotiating. I was trusting an organisation to act in a way of integrity. I took for granted that that's where everyone started."

Rizo with her family

"Whether you have to file a lawsuit or demand it and get it, women need to empower others and educate society about a problem that's still evident," she says.

But the scale of the problem is something which is widely debated.

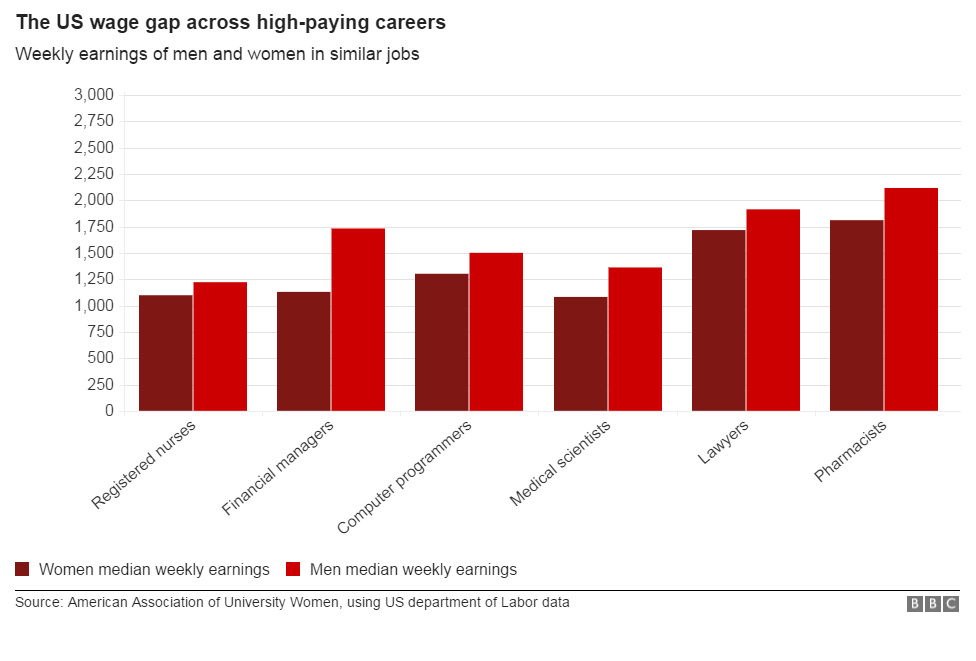

Some critics say the "79 cents for every dollar" statistic is misleading, because it doesn't compare two people working in the same job, with the same background and qualifications. When those factors are taken into account, there still is a gender pay gap, but the percentage difference is much smaller, at around 7%.

Former US Soccer star: 'There are no more excuses'

"The idea that when a young woman graduates, the idea she's going to get paid 79 cents for every dollar a man makes, working in the same job, across our economy is a myth," argues Karin Agness, who is president of the Network of Enlightened Women, a conservative policy group.

Ms Agness believes that the 79 cents statistic gives young graduates a false impression of the workplace they're about to enter.

"It creates a victim mentality in women, and we don't want our young women going into the workforce thinking they are victims just because they are women," she says.

But Lisa Maatz from the AAUW says both measures are valid - one is more general, the other specifically compares similar roles - but both point to a discrepancy which needs to be addressed.

"The gender wage gap has many causes and contributors, including differences in education, experience, occupation and industry, and family responsibilities. But even after accounting for these factors, a gap still remains between men's earnings and women's earnings," argues a White House report on the issue.

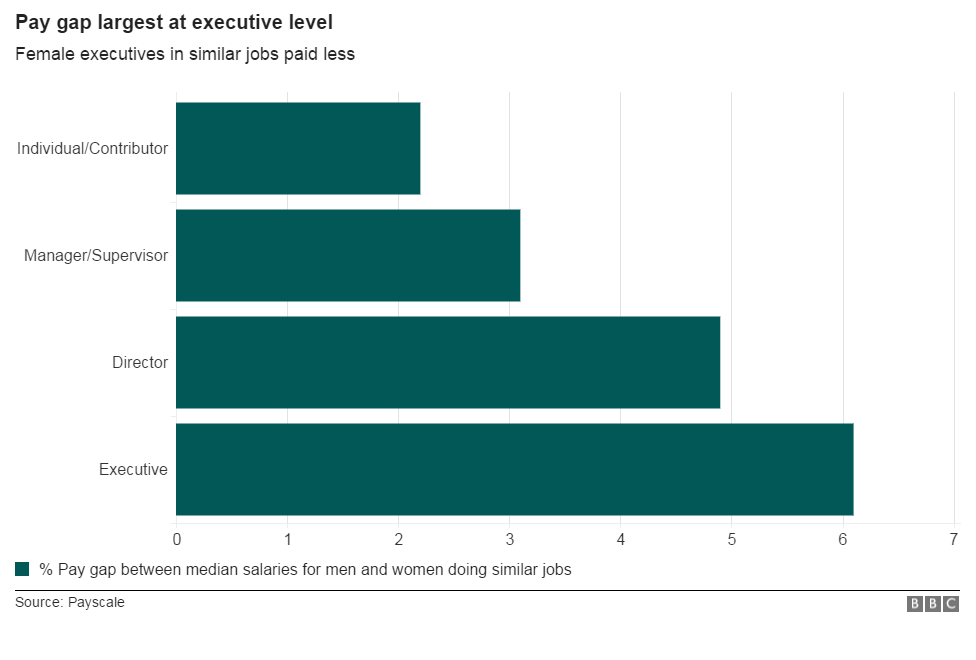

Data on the pay gap for Hispanic and black women shows greater disparities. The gap between similar jobs fluctuates wildly based on the sector. And even controlling for similar jobs, the gap grows for women who are promoted into the director and executive level.

For Ms Maatz, there are other areas which also need to be addressed when it comes to wage disparity, for example the rise of so-called "pink collar" jobs, in which certain roles such as nurses, secretaries and teachers, are devalued simply because more women do them.

But Robin Wright's experience is a reminder that the gender pay gap affects women across all professions. She hopes her example will encourage other women to speak up.

"It's a male dominant workplace society. It always has been. And that's just the history.

"But it has to be unacceptable at this stage."

Follow Rajini Vaidyanathan on Twitter - @BBCRajiniv

- Published19 November 2015

- Published8 March 2016

- Published31 March 2016