Abigail Fisher: Affirmative action plaintiff 'proud' of academic record

- Published

Abigail Fisher in 2016, weeks after her second case at the Supreme Court failed

"I'm a plaintiff in a pretty interesting Supreme Court case that's been to the Supreme Court twice," says the young woman sitting across the table from me, introducing herself for the tape as I adjust the levels on my recorder.

That's putting it mildly. Abigail Fisher's case against the University of Texas at Austin (UT) thrust her into the very centre of heated and overlapping public debates about race and identity, integration, privilege and education in the United States.

Fisher brought the case because she wanted to stop the university from using race in the admissions process, arguing that as a white woman she had lost out on a place because preferential treatment was given to black and other minority students.

But in June 2016 the Supreme Court decided to uphold UT's affirmative action practices and reject her complaint.

Just a couple of weeks later and in her first interview with the national media, I have come to meet her for an early breakfast just outside Austin, Texas, where she lives.

With the cicadas singing in the background and traffic jams already building as the morning rush hour gets under way, she says she doesn't regret her involvement.

"I saw that there was a wrong that was happening, and I had the means and the opportunity to lend my name to this case," she says.

The University of Texas operates two admissions systems. The first grants automatic entry to the top 10% of the graduating class of every high school in the state, and accounts for about 80% of students admitted. Fisher did not make this cut.

University of Texas campus in Austin

The second system, and the one Fisher was challenging, uses a range of factors, including race, to assess students for the final one-fifth of places.

The university's vice president for diversity, Greg Vincent, says that because of residential racial segregation in Texas, affirmative action is needed to help the university promote "both inter-group and intra-group diversity". He argues that such diversity improves the learning experience for all students.

Fisher says she accepts the value of diversity, but disagrees with how the university is seeking to achieve it.

"I would prefer to be in a classroom with people who have had different life experiences than me, and to learn about what they've encountered in their life thus far, and learn from that. And I don't think that's necessarily something that racial diversity will help.

"They can use any other socio-economic diversity, and take time to read people's essays and see that this person who has written this essay will offer a unique perspective on things."

Vincent says the university has looked hard at the alternatives and that their current system is the only way of achieving their goals.

He also points out that when Fisher applied to UT, 168 African-American and Latino students who had higher grades than her were denied access, while some white students with lower grades were admitted.

This has been a key point in public discussion of the case. "Becky with the bad grades" is one of the more publishable epithets thrown her way by critics who just see a young woman suffering a bad case of white privilege.

Fisher's case sparked several critical Twitter memes

"I try not to read any articles. I don't really care what people have to say about me in comments," she says. "I'm proud of the grades that I made. I worked very hard for them."

The day she received her rejection letter from UT, Fisher picked up the phone and called Edward Blum.

A friend of her father's, Blum had spent years looking for a plaintiff to take on affirmative action. He brought this case and a couple of dozen others because he believes the courts, and particularly the Supreme Court, is the best place to achieve policy victories.

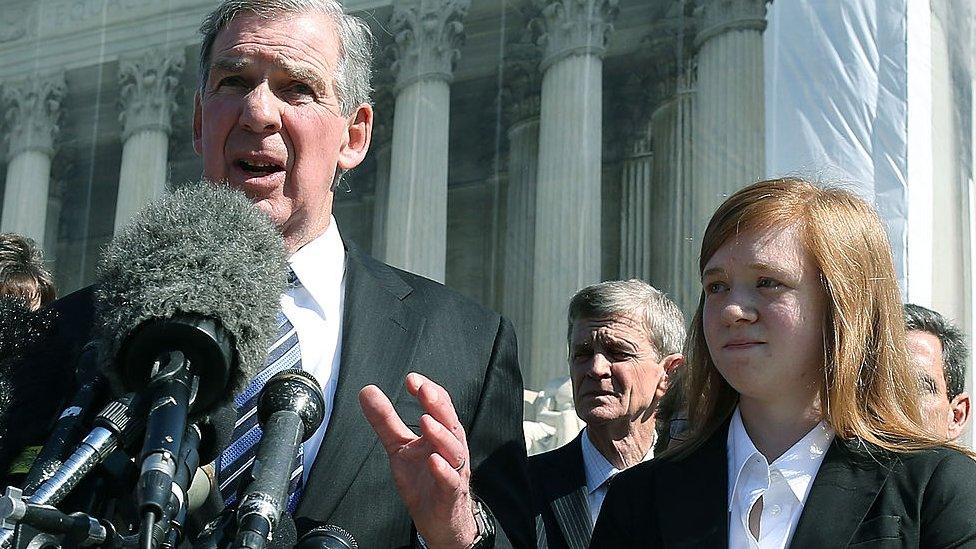

Abigail Fisher with her lawyer during the case's first hearing in 2012

Fisher knew from the start that she wouldn't personally benefit from the case.

"It was going to take longer than the duration of my going to college. It's not like they were going to hand me admission, and that's not really what I wanted."

So in the meantime, she got on with her life, attending Louisiana State University while the case played out in lower courts.

"My dad would call every now and again and go, 'Oh hey, we went to the district court today', or, 'Oh, we're going to New Orleans this week to hear your case'," she says.

But eventually she got a call to say the case was headed to the Supreme Court.

"I was like, 'Okay, I guess I should brush up on the facts'."

In person, Fisher is quiet and unassuming, and when she returned to her finance job the day after the hearing, having told no one where she was going, her colleagues were amazed that she had been all over the news.

She, and many observers, were surprised that the case didn't break in her favour. For years, including at an earlier stage in her case, Justice Anthony Kennedy had been stressing the theme of race neutrality, but this time he cast the decisive vote in favour of affirmative action.

Listen to more

Court in the Centre: How the US Supreme Court has become the busiest and most powerful institution in American politics

BBC World Service, 30 July, 2300 Eastern, and on iPlayer

Fisher points the finger at another judge, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who reportedly, external - minded to rule in Fisher's favour in 2013 - to instead send it for reconsideration by a lower court.

"It's interesting that these justices are easily swayed," Fisher says.

"What it should come down to is that they read the case, make an informed decision, use the constitution as a guiding document, but that's not always how it goes."

After eight years living with the case, and all the downsides, she had hoped for a different outcome.

"It was really disappointing, honestly, but it's a long battle and if this case doesn't end affirmative action then another case will."

But the chance that another case will come before the Supreme Court anytime soon is slim, in part because her advocate, Blum, is rethinking his strategy.

More on the Supreme Court

"The most important thing an advocacy group like mine must consider is the old Hippocratic Oath: do no harm," he says. "Don't bring a case if you think that case could actually make the law worse than it is."

Though he will keep bringing cases to local and state courts - where he thinks the justices are more likely to be on his side - he has abandoned, for now, his plans to take his fight against affirmative action in front of the Supreme Court.

"There are times in which you are wise to walk away from that fight, and perhaps at this point it might be wise to walk away from the fight about the permissibility about using race and ethnicity in university admissions."

For a man who has been such a driving force behind the legal battle over affirmative action, that acknowledgement is hugely significant.

Obama has nominated Merrick Garland to sit on the Supreme Court, but Republican lawmakers have declined to hold hearings

But it undoubtedly raises the stakes for this year's presidential election, too. Republicans in the US Senate are refusing to consider President Barack Obama's nominee for the current vacancy on the court until after the election. With one or two more vacancies expected in the next president's four year term, whoever gets to nominate those justices could significantly shape the future of the court.

Back in sweltering Texas, breakfast is over. Fisher will likely keep an eye on those Supreme Court appointments. She wants the public to learn more about the court, and she believes another case will come along which will overturn affirmative action.

It has been, she says, "really cool to be a part of it," but for now she will step back from the battle, and focus on her career.

- Published8 February 2024