Mother's quest to find missing daughter in Ghost Ship ashes

- Published

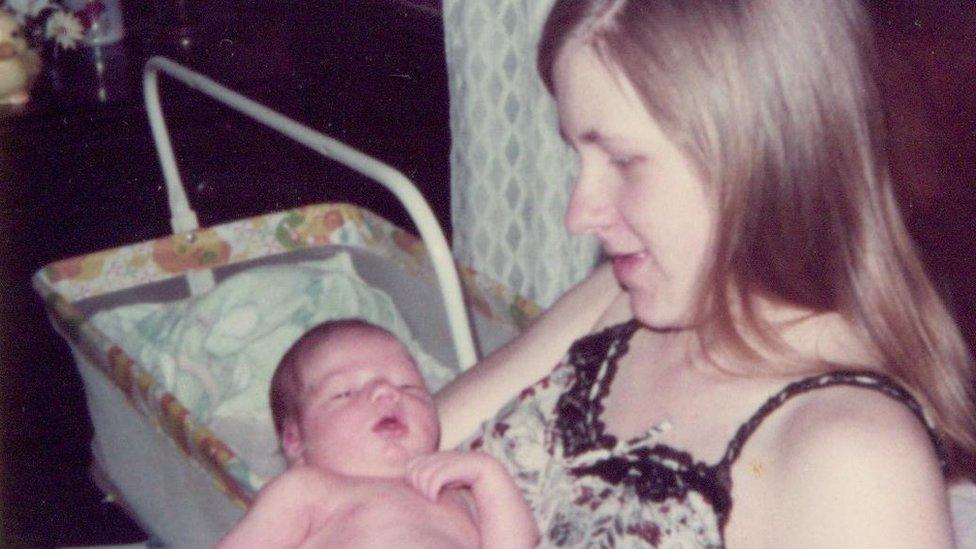

When a fire at an underground music event in California killed 36, families whose adult children had been missing for months or years were among those who feared the worst. Daleen Berry explains why she went looking for her daughter at the Ghost Ship.

I had moved across the country to find my daughter, Trista, but the deadly warehouse fire in Oakland in December forced me to take the first step, the one I had been dreading.

After hearing that people actually lived in the warehouse of artists' studios and performance spaces known as the Ghost Ship, I needed to see for myself, to ensure Trista - the name I'll call her to protect her privacy - was not among the dead.

At the scene many had gathered to grieve and pay their respects. There were also people like me, who had lost touch with their loved ones for weeks, months, or even years, and were fearful they were inside when the fire started.

I took the advice of an officer and drove to the Alameda County Sheriff's Office, where they had set up a makeshift family assistance centre to provide emotional support and privacy for the family members. We waited for updates from Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf and found comfort in a safe place, together.

On one wall inside the centre were three lists: the confirmed dead, those who had been located and were safe, and those still reported as missing. On that last list were about 150 names.

I knew then I was far from alone. Somehow, it made it easier to speak the words I'd refused to let myself believe: "My daughter is missing."

Unlike TV, where missing people are portrayed as victims of sexual trafficking or serial murderers, most adults disappear for far less sinister reasons. As of late December, the California justice department had 20,470 reports of missing persons in the state.

Of those, 7,854 are like my daughter, classified as "voluntary missing adults".

More than 8,000 are runaways.

Another 1,060 people were taken by a family member, while 764 disappeared under suspicious circumstances and 114 went missing during a catastrophe.

At just 51, stranger abduction cases number the lowest.

The 48 hours in the family assistance centre were among the most painful in my life, as I struggled to answer one question after another.

When did you last hear from your daughter?

June.

Did you file a missing persons report?

No.

Do you have a preferred funeral home?

No.

Oakland residents held a vigil for victims of the fire

A few months earlier I had packed up everything I owned, leaving behind family and friends to follow Trista's path west. I didn't tell them the real reason I was leaving - I wouldn't rest until I knew where Trista was.

A kind and caring free spirit, Trista had gravitated to places like the Ghost Ship in the past. I knew that she might have lived there because this was her community: musicians, artists and other creative people.

When I went to work for a small start-up in Oakland in 2009, she lived with me, then later followed me back to West Virginia.

From there she travelled to Chicago, New York and Philadelphia, meeting up with fellow musicians. She was content to live in her own world, collecting items cast to the kerb and transforming them into beautiful works of art.

But by 2014, while I was put the finishing touches on a true crime book about a missing daughter, Trista was becoming increasingly distant and withdrawn.

By then, my daughter's temporary forays into seclusion had become legendary.

I had been trying to understand them for 10 years because, at times weeks or even months would pass without so much as a word.

But I always knew she would reach out to someone - my sister, her brother, my mother.

Not this time, though.

Trista terminated all but two ties in February 2015, when she returned to the Bay Area.

By June 2016, the last time I heard from her, she severed the rest.

I called her brother in San Francisco: he hadn't heard from her in a year.

She changed her cell phone number. All of my emails to her bounced back.

"The email account that you tried to reach does not exist," Google repeatedly told me.

This wasn't my first trip to Oakland to look for Trista. I drove there one month before the fire. I needed to check out our old neighbourhood in case my daughter had returned. She hadn't.

Some of the victims of the fire were LGBT or made outcasts in other ways; people who believed their families had given up on them - or vice versa.

But families like mine with missing children don't give up. We may stumble around, accidentally making matters worse.

But it is never intentional. I met a few other parents whose children died in the fire.

They didn't leave until the last handful of charred ashes was carried from the scene - when they knew for sure their child was truly, finally gone.

A day after the fire, I finally forced myself to open the laptop Trista left behind in West Virginia a year earlier.

I spent hours reaching out to her friends, fellow musicians, and a previous employer.

They hadn't heard from her in years. No one knew anything.

It was like Trista had closed the door on her old life, never to reopen it again.

But I couldn't just wait for a phone call telling me if my daughter was dead or alive. I had to know myself, so I drove to Oakland from Sacramento.

And waited, for as long as it took.

After spending two days at the family services centre, I stumbled into my hotel room, still struggling with the enormity of it all. What will I do if they find her? What if they don't?

The following morning, one of the mental health professionals on hand to help the families guided me down a corridor and into an office.

There, two women greeted me from the state justice department's missing persons unit.

"We've located 1,000 people since 2001," they said.

"Even a few live Jane Does," they added hopefully.

They asked more questions. I signed more paperwork. Then, after careful instructions, a gloved hand gave me what looked like a pink and white emery board.

I opened my mouth, did as they directed, and handed over my saliva - my DNA - and the only link to my daughter.

I just wanted to find Trista. Beg for her forgiveness. Tell her I was sorry - for me, for my mistakes, and for not understanding her well enough. For my family, who did likewise, and in whose heart she still holds a sacred place.

Given that all 36 victims of the Ghost Ship fire have been identified, I have to believe Trista is still alive. Still out there, somewhere.

Like the 150 or so other worried mothers of those on the missing list, I have but one thought: I love you.

Please come back to me.

Or - at the very least - phone home.

Daleen Berry is a New York Times bestselling writer and author of several books, including Shatter the Silence and Pretty Little Killers.