Canadians avoid calling Cleveland team 'Indians'

- Published

While their mascot has changed, the "Chief Wahoo" logo of the Cleveland Indians remains

The Cleveland Indians are the only thing standing between the Toronto Blue Jays and the World Series. While that alone could earn the ire of most baseball-loving Canadians, many find their very name offensive.

Since it became clear that Toronto would have to face Cleveland in the American League Championship Series, a movement has grown across Canada to not say the team's full name because of its appropriation of indigenous culture.

Jesse Wente, a prominent cultural critic and self-described "Ojibwe dude," blasted the team and sports media on Twitter.

"I think we need to disempower and devalue the worth of these mascots and logos," Wente told the BBC World Service.

Jesse Wente says Canadians should not use the Cleveland team's name

He is not alone. Jerry Howarth, the Jays' play-by-play announcer on Sportsnet, told a local radio programme that he hasn't used team names like the Indians or the Braves since a fan wrote him an impassioned letter in 1992.

"He said 'Jerry, I appreciate your work but in the World Series, it was so offensive to have the tomahawk chop and to have people talk about the powwows on the mound'," Howarth told The Fan 590. "He just wrote it in such a loving, kind way. He said 'I would really appreciate it if you would think about what you say with those teams.'"

Other Canadian sportscasters are following his lead. Hashtags like #notyourmascot and #ClevelandNotIndians have been trending in Canada.

The National Congress of American Indians has repeatedly called on sports teams to stop using Native-American stereotypes as mascots or slurs in their branding.

In Canada, those requests resonate with a wide audience.

"I think that indigenous rights and indigenous politics are much more visible in Canada, and they play a more significant role nationally than in the United States," Rima Wilkes, a sociologist at the University of British Columbia, told the BBC.

A DJ from A Tribe called Red (seen playing here in New Orleans) wore a parody "Cleveland Caucasians" t-shirt

Almost 4% of the Canadian population claim aboriginal identity, compared to just about 1.7% in the United States. In some parts of Canada, such as the Nunavut, Northwest Territories and the Yukon, and in cities such as Winnipeg and Thunder Bay, the population is much more visible.

The country is currently engaged in a national conversation on indigenous rights. In Toronto, Canada's largest city, public schools now open each day with the national anthem, followed by a tribute to the Indigenous people on whose lands the schools are built.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has launched an official inquiry into missing and murdered indigenous girls and women, and the country is wrestling with the damning findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which investigated Canada's history of forcing aboriginal children to attend residential schools.

, external, externalCanada promises 'full reconciliation'

Not everyone sees the link between Canada's residential schools and sports teams' names. Last February, Rosie Dimanno, a sports columnist at the Toronto Star, came out against a group of "professional taste inquisitors" who wanted to ban students from wearing clothes with offensive logos like those used by Cleveland.

Blue Jays will play against the Indians for the American League title

"These are expressions of respect, a borrowing of prestige and significance. And we are all allowed to borrow because nobody owns history, nobody has a patent on cultural imagery," she argued.

In many ways, refusing to say the Cleveland team's full name is an easy act of solidarity for non-indigenous Canadians, says Eve Tuck, a professor of indigenous studies at the University of Toronto and a member of the Aleut Community of St Paul Island, Alaska.

Protestors in Minnesota voice their opinion about Cleveland Indians mascot Chief Wahoo in 2014

"I think it is a kind of easy, morally self-satisfied position to be like, 'well we don't have that here,' but of course Canada does," she told the BBC.

Indigenous people are about twice as likely to be unemployed as a non-indigenous Canadian and they are ten times more likely to be incarcerated, according to Statistics Canada. While aboriginal women make up just over 4% of the population, they represent 16% of all murder victims, according to the RCMP.

Like Colin Kaepernick's decision to take a knee during the national anthem, Tuck hopes the growing refusal to say the team's name will spark a wider dialogue.

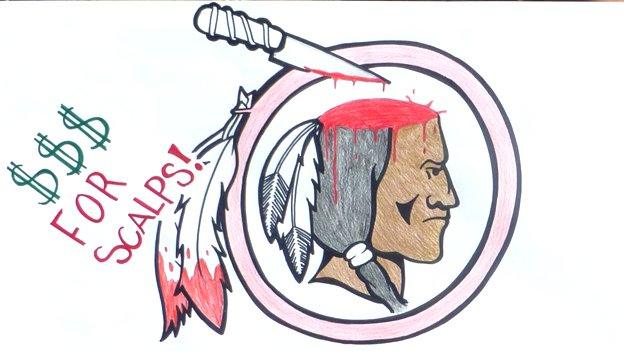

"I think we need to see other forms of refusal around these mascots, and the making of money around the circulation of these dehumanising images," she said.

"Slider", Cleveland's mascot on the side lines

The Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) is currently intervening in a complaint against the City of Mississauga for its support of local sports teams the Mississauga Braves, Mississauga Chiefs, Lorne Park Ojibwa, Meadowvale Mohawks and Mississauga Reps.

The OHRC's chief commissioner, Renu Mandhane says that interviewing young indigenous people has opened her eyes to the power of team names.

"Many of these indigenous mascots are very stereotypical, even some of them caricatures of indigenous people," she told the BBC. "That can be really difficult to navigate when you're a young person and you're trying to establish what it means to be a modern indigenous person,"

She says she won't use the Cleveland team's full name - and advises other people to do the same.

- Published5 November 2015

- Published9 December 2014

- Published22 August 2014