Canadian reporter Ed Ou barred from entering US

- Published

Canadian journalist Ed Ou was barred from entering the US after he refused to let officials look at his phone in order to protect sources.

A Canadian reporter was barred from entering the US. Is this the beginning of the end of press freedom?

Ed Ou is used to crossing borders.

The award-winning Canadian photojournalist has spent the past decade travelling to the kinds of places where being in the media can be a hazard to your health: Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, Egypt and Turkey, to name a few.

So when he booked a flight in October to the US from Canada to cover the Standing Rock pipeline protests in North Dakota for the Canadian Broadcasting Company, he was relieved to be somewhere with press freedoms.

"In my mind I had nothing to hide. [America] is actually one of the few places in the world where you can just say you're a journalist," he told the BBC.

But when he told US border officials at the Vancouver airport he was travelling to North Dakota to cover Standing Rock, he says they pulled him aside and proceeded to interrogate him for six hours.

When he refused to unlock his mobile on the grounds that it contained confidential information about sources, they forcibly took his Sim cards and made copies of his reporter's notebook and personal diary.

Then they barred him from entering the US.

Legal experts and free speech advocates have spoken out against his treatment at the border, and say America's press freedom laws don't stand a chance against a government that has grown increasingly hostile towards the press.

Ed Ou was forced to leave Turkey last December along with other journalists who covered political unrest in the region.

The American Civil Liberties Union, external, which is representing Mr Ou, and the Canadian Journalists for Free Expression, external have both condemned the incident. But according to the law, what happened at the US-Canada border is entirely legal.

Border officials have a right to search all property, including electronic devices, within 100 miles (165km) of any "external US boundary" without a warrant or reasonable grounds for suspicion.

According to a 2009 directive, sensitive materials such as "medical records and work-related information carried by journalists" receive no special treatment outside of pre-existing federal laws, external and policies, which are weak at best, according to media law experts.

"Journalists in the US generally don't have to reveal their sources because the government doesn't seek them," says Floyd Abrams, who represented New York Times reporter Judith Miller in her efforts to keep a source confidential.

But that's not guaranteed. The Obama administration has pursued legal action against leakers such as Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning, and has subpoenaed many journalists to try to get them to testify against their sources.

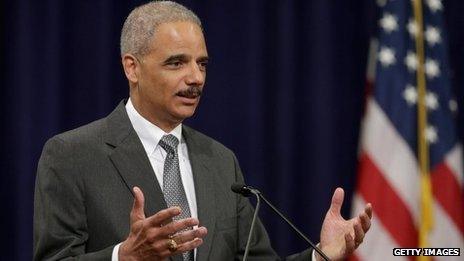

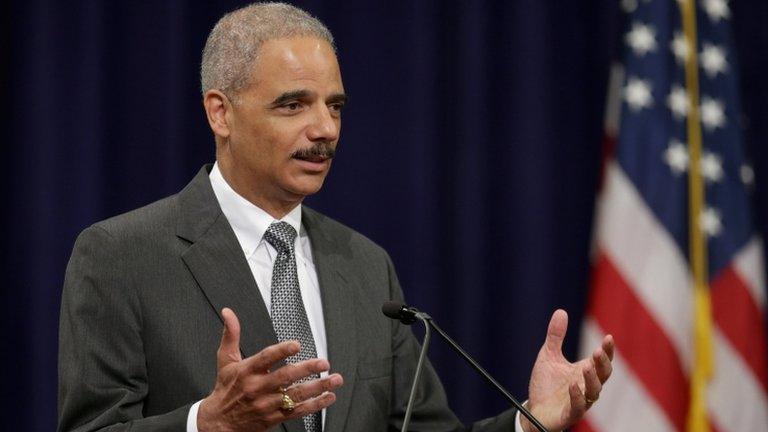

Attorney General Eric Holder signed a subpoena for the records of Fox News reporters while a deputy did so for multiple AP offices

In 2015, Attorney General Eric Holder promised not to prosecute journalists, external for doing their job. But the directive he laid out in a departmental memo is a guideline and not a law, and it remains to be seen what will come of it as a new administration takes hold.

Lucy Dalglish, a lawyer who served with the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, says the treatment of Mr Ou at the border is "outrageous" and says it reminds her of some of the complaints she heard from journalists immediately following 9/11.

"People should be able to come into this country and cover stories. The most troubling thing would be if they targeted him because he was a journalist," she says.

The Customs and Border Protection agency told the BBC it cannot comment on individual cases, but that people who feel they have been treated unfairly can complain to the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees border security.

For his part, Mr Ou says the issue of privacy and government surveillance isn't limited to the US. The Canadian spy agency recently admitted keeping a database with people's information, and Montreal police admitted spying on journalists' phones.

"This is what an authoritarian regime would do, and I should know, because I've spent the last 10 years covering them," he says.

- Published31 May 2013

- Published12 September 2016