Safety Pin Box aims to get white people to step out of theirs

- Published

Safety Pin Box, a new monthly subscription service, has a lofty goal - to help white people learn how to root out racism while simultaneously paying black activists for their time.

While on vacation in Jamaica together just after the US election day, activists Leslie Mac and Marissa Jenae Johnson and a group of friends got to talking about safety pins.

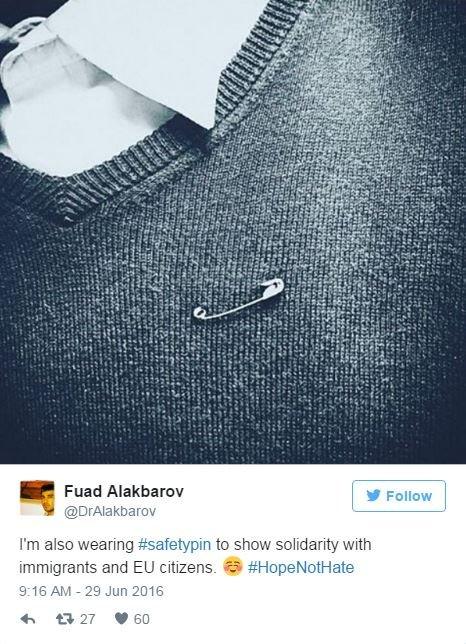

Specifically, the safety pin phenomena gaining momentum among upset liberal voters in the wake of Donald Trump's victory.

The idea was that white people who wanted to signify solidarity with people of colour could show it by wearing a safety pin on their shirts. The concept was originally created by a woman in the UK after an increase in incidents of racially motivated hate crimes and attacks after the Brexit vote. The safety pin would identify the wearer as a "safe" person to go to during a racially motivated or homophobic attack.

In the US, however, the safety pin quickly became the subject of ridicule. Mac remembers thinking the gesture was hollow, easily co-opted and the "very least that one could do to show solidarity". It wasn't the first time well-intentioned white people had missed the mark.

In the same poolside conversation in Jamaica, the women began reading off their phones from the emails that they had received from anxious white people eager to battle racial injustice, but with no clue how to do so.

Safety Pin Box founders Leslie Mac and Marissa Jenae Johnson

As experienced social justice organisers with large Twitter followings, both Mac and Johnson (best known for the Black Lives Matter protest that interrupted, external then-candidate for president Bernie Sanders during a speech in Seattle, Washington) were often on the receiving end of calls for help and instruction from white "allies". They say this disproportionately happens to black women activists. Responding to the same questions over and over again had become exhausting.

"We each took our phones out and had three rounds just reading out these messages," says Mac.

Over and over, Mac and Johnson were asked, "How do I become a better ally?" or solicited for their take on whatever the most recent popular article, controversy or campaign surrounding race happened to be.

"We realised how much time that was taking," says Johnson. "We were all having to have the same individual conversations, and there had to be a more efficient way to do this."

In this moment, Mac and Johnson saw an opportunity to create both a business venture as well as a new model to support activism. Together, they co-founded Safety Pin Box, external, a monthly subscription service for "white people striving to be allies in the fight for Black Liberation".

For between $25 (for an electronic membership) and $100 (for a physical box mailed to subscribers) (£19.75 to £78.99) a month, subscription members are sent a set of tasks that will help them "do tangible ally work and support black women in both power and deed". Johnson says that the target customer is a white person who already recognises his white privilege but "wants to learn, who believes in giving back to black people, is humble and willing to make mistakes".

Marissa Johnson, left, after taking the microphone at a Bernie Sanders speech in Seattle in 2015

"This [is a] huge group of white folks," says Mac. "They've gone and read Ta-Nehisi Coates' book, they have a good understanding of this puzzle of white supremacy and racial injustice, and they're at a moment where they don't know where to go with that."

The first sample task, for example, helps users chart the ways in which they wield power in everyday life - whether it is how they spend money, or in their jobs or their church - and how to redirect it to benefit people of colour.

Both Mac and Johnson have characterised Safety Pin Box as a business, not a charity, though they distribute the funds raised from subscriptions to other black women who are also involved in various forms of activism. They estimate they have over 300 subscribers so far.

Their choice to keep the identities of the women who are receiving proceeds private, and the mere fact that they would accept money at all for the service, has become a flashpoint for criticism. Safety Pin Box has been called a "scam" by opponents on Twitter, and conservative bloggers pounced on the concept as a cynical way for the women to capitalize on "white guilt".

"This Safety Pin Box is just a beauty box for lazy performatively woke white people," one critic tweeted, external.

"Anyone willing to participate in this grand scam has far more money than common sense," another blogger wrote, external.

Mac and Johnson say that actually paying black women activists for their help demonstrates commitment to the cause, while allowing them to continue to do the arduous work of organising in a more sustainable fashion.

"[Society] devalues the work of black people working for their liberation. It becomes a very toxic environment. You're asked to give everything of yourself," says Mac. "We need to figure out how to make this a long-term proposition ... Why can't we build a business that gives back to our community and still respects the value of what we do? I don't see them as mutually exclusive."

Subscriber Marilyn Boyd, a 59-year-old woman who lives in a mostly white, conservative community in rural New York state, had no problem forking over the $100-a-month subscription fee.

More from the BBC:

"It's as good as a college course - why the hell wouldn't I pay for this?" she says. "I love the fact that Leslie and Marissa have put together something that is simple for people like me, who are not tech savvy, who have not grown up activists, who have not had this opportunity before so we can catch up."

Similarly, subscriber Mary Byron in suburban New Jersey says she has no idea why the price of the subscription is the point of greatest contention.

"Education is not free," she says. "I would expect that I'm going to pay for something that's going to be of value, and I want to support the people who create those things."

Johnson says that she is already surprised by the outpouring of enthusiasm and relief that she has seen in the Safety Pin Box Facebook group, which is closed to outsiders. Both she and Mac envision a future where Safety Pin Box members can meet in person or take part in actions happening in their cities.

"We're able to provide a sort of therapy, a sort of life coach for people in that we're trying to help them, and create a space to process their emotions around race," she says. "People feel super isolated around this topic - now they're able to connect with other people like them who also want to learn and grow."

That's certainly been true for Boyd, who says she quit Facebook after being attacked online for her support of Black Lives Matter by her law enforcement-connected friends. Now, she says, she has a place to go and be a part of a positive community of like-minded white allies.

"I'm hoping the more I learn, the less scared I will get," she says.