Canada's Project Naming: Identifying the unidentified

- Published

Bella Lyall-Wilcox carrying her sister, Betty Lyall Brewster

A photo identifying effort by Canada's national archives that started in the country's remote north is helping name indigenous Canadians in archival images - and bringing the country a step closer to reconciliation by correcting historical wrongs.

Janet Brewster did not expect to see a baby photo of her mother in a press release.

But there she was, Ms Brewster was sure of it, her mother Betty's chubby arms resting on her older sister's back, eyes looking directly at the camera.

"It was the eyes, eyebrows and hair that really struck me and I thought 'Oh my gosh, that has to be my mom,' because it looked so much like my youngest son," she says.

Ms Brewster emailed the image to her mother, now 69, who confirmed it was indeed her as a child, along with Ms Brewster's aunt Bella, their two brothers and a third, still unnamed, boy.

Left to right: unknown boy, Johnny Lyall, Pat Napatchee Lyall, Bella Ningyooga Wilcox (née Lyall) carrying her baby sister Betty Novalinga Brewster (née Lyall), probably at Fort Ross, Nunavut, summer 1948.

The image of the siblings, a snapshot taken when the family was living in a remote Hudson's Bay Company, external trading post and spent many of their days together, was being used by Library and Archives Canada to promote Project Naming, an initiative to help communities identify indigenous Canadians captured in photos in the archive's extensive collection.

That coincidence eventually led Betty Brewster to identifying a handful of other previously anonymous Inuit people in digitised images at the national archives, and other images of her and Bella, now 78.

"It started with that first photograph," Ms Brewster says.

Project Naming was first launched as a small one-off project with the goal of identifying Inuit people from the territory of Nunavut who had been photographed by Canadian government bureaucrats and employees working in the far north from the late 1800s to the mid-20th century.

The images rarely made their way back to the remote communities, but eventually ended up in the national archives, a repository responsible for collecting all significant government records in need of preservation.

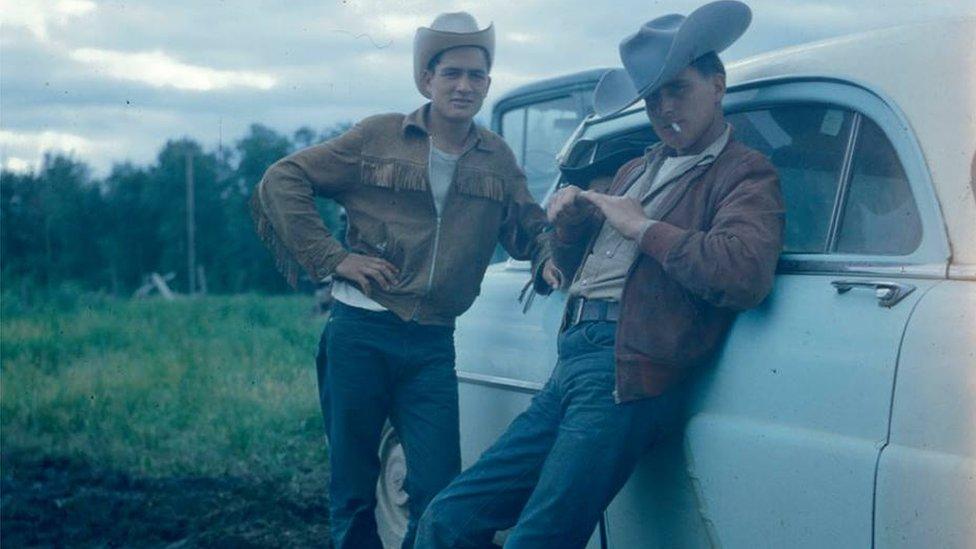

Two men photographed at Swan River, Manitoba, June 1956.

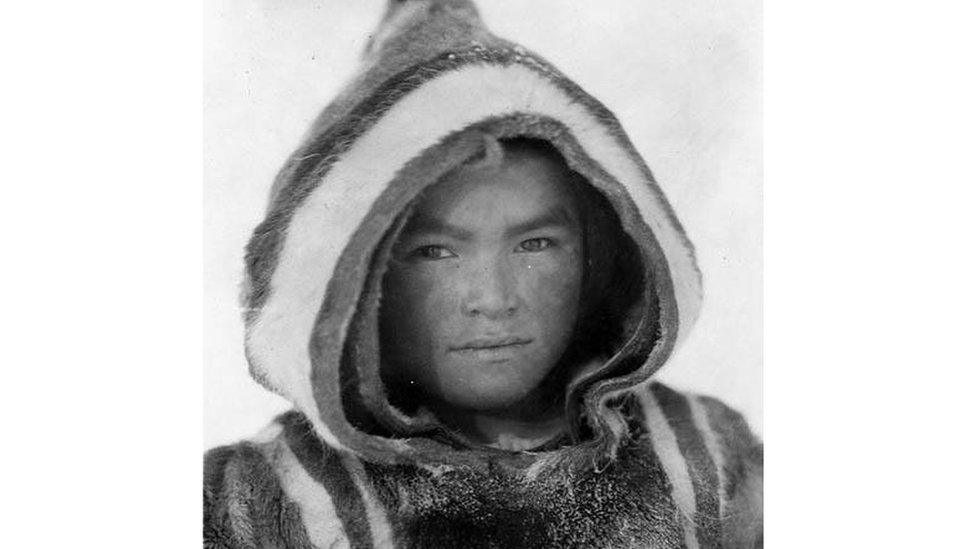

Portrait of Angmarlik, a respected Inuit leader at Qikiqtat in Cumberland Sound from the early 20th century until his death in the late 1940s or early 1950s.

As was convention at the time, many of the white people in the images were named for the record. The indigenous subjects were not.

"Most photos were described as being native, native-type, half-breed, Eskimo, or simply ignored in the photographs," says Beth Greenhorn, who has been heading the project for the archives since 2003.

"Terminology has changed and, because we are dealing with historical records that were created decades ago, I find it a bit painful to go through."

Updating the official record and terminology is one part of the project.

The other is helping youth connect with their community elders to better understand their past.

Ms Brewster says most of her family now knows the names of the children in the old images. Like family photos do, the images spurred a conversation about what their lives were like and where they were living.

Unidentified child in Cape Dorset (Kinngait), Nunavut, 1929

Beth Greenhorn on connecting families with archive photos

Among the stories they shared with their family were Betty Brewster's time as an interpreter-translator for the Nunavut land claims agreement that led to the creation of Canada's newest territory.

"When you talk about reconciliation and about moving forward as a country and as indigenous people, Inuit people living in this country, naming people in those historic photographs is so important," Ms Brewster says.

"When you acknowledge people have names, it lends more credence to their life experience."

The project was inspired by Murray Angus, who oversaw a college programme for Inuit youth that brought them to the Canadian capital of Ottawa to study Inuit history, land claims, culture and language.

In the early days of the project, the pictures were transferred onto CDs and brought north by the students to be shared at community gatherings and to visits to elders for identification.

The project now uses social media outreach on Twitter and Facebook, external, where people can share the photos and offer clues.

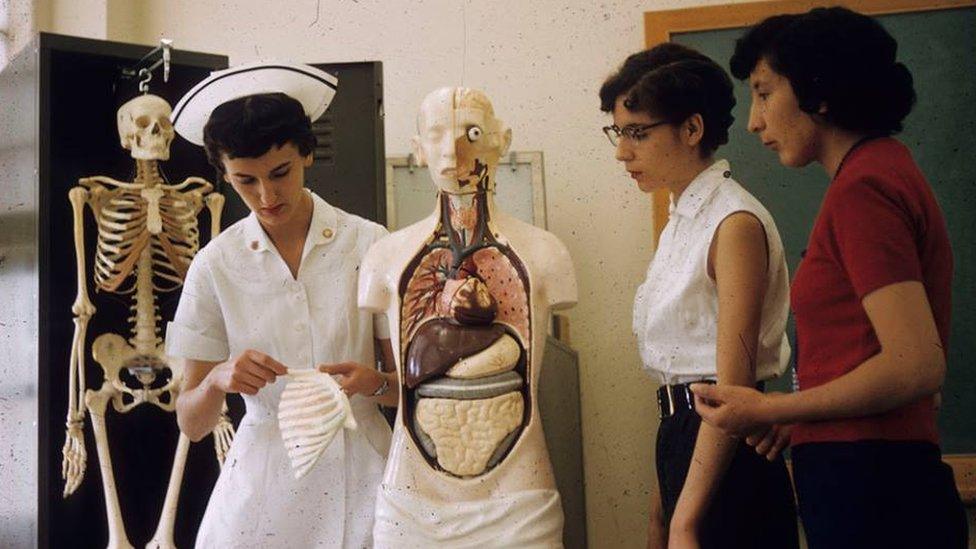

Unnamed women in Calgary, Alberta, 1955

Cree veteran James Sutherland bringing furs to the Hudson's Bay Company post manager, Ron Duncan, in Moose Factory Island, Ontario, January 1946

Ms Greenhorn says it gives her "goosebumps" when she sees someone recognise a family member or even a photograph of their much younger selves in the images.

"It is this very elemental human reaction that it just drives the project forward," she says.

Images, now posted weekly, showcase the austere beauty of Canada's Arctic regions and its people, and glimpses into the past lives of ndigenous Canadians across what was a largely rural nation.

They also portray some of the darker parts of Canada's relationship with its indigenous people, including photos of children in the residential school system, which removed them from their homes and aimed to eliminate their culture.

The project is now entering its 15th year and has been expanded to include anonymous photographs from First Nations, Metis and Inuit people across Canada and all its northern territories.

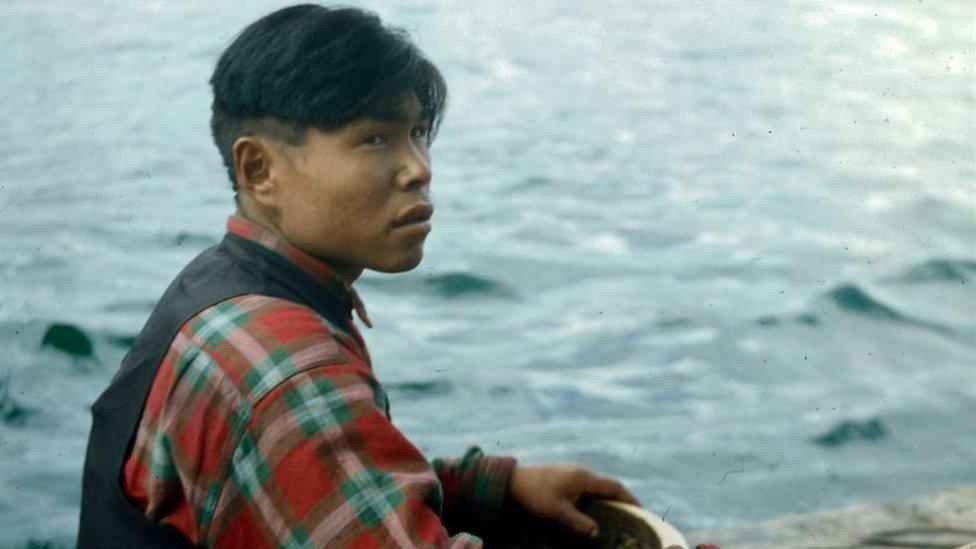

Johnny Makalu (Morgan) from Kangiqsualujjuaq, Quebec, August 1960.

Since the project's launch in 2002, about 10,000 images have been digitised. More than 2,500 people, places, and activities they are participating in have been identified.

Ms Greenhorn admits the number does not seem high but believes that each person named counts.

"Some of these portraits are so beautiful and they represent a life that was lived, someone that's contributed to their community that had a family and to not have a name for them is sad," she says.

"So when you do make a connection, when you get a name and add it to the record it's exciting and you think OK - there's one more done."

- Published7 December 2016

- Published8 December 2016

- Published15 December 2016

- Published9 December 2016