Electronics ban: How will new US and UK rules affect me?

- Published

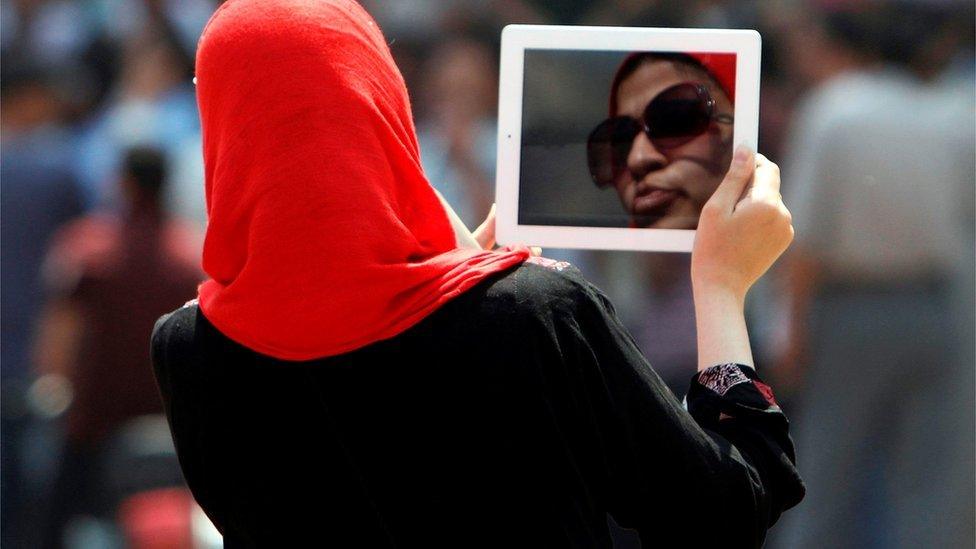

Laptops in the cabin will be banned on some flights within days

The United States and United Kingdom have announced that laptops, e-readers and almost any other electronic device that is not a phone will be banned from cabin luggage on some flights.

The US rule only applies to 10 airports, but one of those is the world's busiest international airport - Dubai International.

The UK ban does not include Dubai, and only has six countries on the list.

Which items are affected?

The US rule is broad and wide-ranging, affecting almost anything that is not a phone.

It says: "Electronic devices larger than a cell phone/smart phone will not be allowed to be carried onboard the aircraft in carry-on luggage or other accessible property."

Anything larger will have to go in checked luggage in the hold.

But the advice does not define that size with any measurements, saying simply that "the approximate size of a commonly available smartphone is considered to be a guideline for passengers".

The US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) gave a list of examples, but said it was not exhaustive:

Laptops

Tablets

E-readers

Cameras

Portable DVD players

Electronic game units larger than a smartphone

Travel printers/scanners

For US-bound passengers, it is not clear if the vague sizing could cause problems with interpretation, especially when it comes to larger phones or so-called "phablets" such as the iPhone 7 Plus.

In an accompanying document, the DHS said "their size is well understood by most passengers who fly internationally".

Advertising for Nintendo's new console specifically highlighted its use on a plane

The examples specifically mention both portable media players and game systems.

But "necessary medical devices" will be allowed on board flights - after a security check.

The UK has offered clearer parameters: nothing bigger than 16cm (6.3ins) long, 9.3cm (3.6ins) wide or 1.5cm (0.6ins) deep will be allowed into the cabin - which means mobiles like the larger iPhone Plus will still be allowed.

Which airports are affected?

The new rules apply to 10 airports if you are flying to the US:

Queen Alia International, Amman, Jordan

Cairo International Airport, Egypt

Ataturk Airport, Istanbul, Turkey

King Abdulaziz International, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

King Khalid International, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Kuwait International Airport

Mohammed V International, Casablanca, Morocco

Hamad International, Doha, Qatar

Dubai International, United Arab Emirates

Abu Dhabi International, United Arab Emirates

Dubai - the world's busiest international airport - makes the list

The DHS said it had chosen the airports "based on the current threat picture" but did not provide any more details. It said it might add more airports in future.

There is also no time limit on the rules - they will stay in place "until the threat changes".

The rule change also requires no additional Transportation Security Administration (TSA) agents, US authorities said - any increased security cost will be borne by the affected airports.

For UK-bound travellers, it affects all flights coming from:

Turkey

Lebanon

Jordan

Egypt

Tunisia

Saudi Arabia

This means it affects 14 airlines including British Airways, Easyjet and Monarch.

What about connecting flights?

If you are on a business trip from Asia to the US, it is likely that a Middle Eastern airport like Dubai could be part of your itinerary.

But the document detailing the enhanced security refers to "last point of departure airports" - so if you change planes at one of the affected airports for the last leg of your trip, the rules still apply.

So, for example, going from Dubai to New York - a 14-hour flight - will leave you without a laptop or other device, no matter where you started your journey from.

"TSA recommends passengers transferring at one of the 10 affected airports place any large personal electronic devices in their checked bags upon check-in at their originating airport," the official advice says.

What's the logic behind the ban?

In a statement, the Department of Homeland Security said it was basing its decisions on "evaluated intelligence".

It said terrorists "continue to target commercial aviation" and are trying to find "innovative methods" to make such attacks - including hiding explosives in consumer electronics.

"We note that disseminated propaganda from various terrorist groups is encouraging attacks on aviation, to include tactics to circumvent aviation security."

"We have reason to be concerned," the agency said - but did not address any specific threat.

The TSA dictates flight safety rules on inbound flight, which airlines must follow

Instead, they cited three examples of attacks that caused concern: the 2015 downing of an aircraft in Egypt, the attempt to down an airliner in Somalia in 2016, and the 2016 armed attacks against airports in Brussels and Istanbul.

Some of the banned devices may not be much larger than a mobile phone, adding to the confusion. Homeland Security said they were allowing phones simply because the new rules aim "to balance risk with impacts to the travelling public".

Jim Termini, whose company Redline specialises in airport security, said that laptops could be modified to allow small devices to be hidden inside - as had happened in Somalia.

"The device functioned prematurely and the guy carrying it was ejected from the plane rather violently. But it did demonstrate that this method of operation in concealing an improvised explosive device within a large electrical device is a valid way of attempting to smuggle a threat item onboard an aircraft."

Mr Termini added that laptops could be adapted to create space where the battery is housed in order to allow an explosive device to be placed inside. "If a device is opened and turned on, you can prove functionality while it is still a valid IED (improvised explosive device), and the problem with these devices is that they are incredibly difficult to identify with X-ray technology".

But what is the difference between being in the cabin, or in the hold?

Can an airline or airport refuse?

No. As part of the legal agreements that allow commercial airlines to enter US airspace, they must abide by TSA security rules.

The UK government also says that direct flights can only "continue to operate to the UK subject to these new measures being in place".

The DHS points out that the new rules will apply to a very small proportion of travellers - just 10 of the 250 or so airports which fly to the US.

Meanwhile, the UK says "decisions to make changes to our aviation security regime are never taken lightly" and it will work to "minimise any disruption these new measures may cause".

"A small percentage of flights to the United States will be affected, and the exact number of flights will vary on a day to day basis," it said.

Will insurance cover items placed in the hold?

Asked by readers Mohamed and Richard Simpson

Generally speaking, no.

The Association of British Insurers (ABI) says that most travel insurance policies simply will not cover theft of "unattended belongings" which you cannot see or are not close to you.

"Your insurance will not cover valuables that go missing from checked in baggage," it says.

"Your baggage is considered checked in from the time you hand it over to the airline at the airport until the time you pick it up at your destination."

Baggage piled high in Gatwick on Christmas Eve, 2013, during bad weather delays

In light of the new restrictions, Mark Shepherd from the ABI said policies vary, and you should check your own.

"Some travellers may find they also have additional cover under a household contents policy for gadgets outside of the home," he said.

"We do know some insurers already take a flexible approach to claims if a passenger has been forced to put items in the hold by circumstances out of their control."

But, he said, "it may be sensible to leave valuables at home" if you're flying through one of the affected airports.

What if the airline damages my belongings or they are stolen?

Asked by readers Graham Philips and Dave Humphreys

If your suitcase or other property is damaged in the hold, do not leave the baggage hall. You must contact customer services to lodge what's called a "property irregularity report".

You can do this with some airlines within a few days, provided you have all your travel documents and the tags are still intact, but it's far better to do so at the airport before you leave.

But you're unlikely to be repaid in full.

The Montreal Convention, which covers international air travel rules, does make the airline responsible for your baggage.

But it's all rather complicated. They even use a special international currency, XDR (special drawing rights), to define how much they owe.

Airline liability is limited to 17 XDR - about $23 or £18.50 - per kilogram of baggage, up to a maximum of 1,000 XDR (about $1,360 or £1,090).

You can get around this by making what's called "a special declaration of interest" for very expensive items at check-in, and paying an extra fee.

Make sure you report any damage before you leave the baggage hall

But it's still not the carrier's fault if "the damage resulted from the inherent defect, quality or vice of the baggage".

Essentially, they're unlikely to accept responsibility for an expensive laptop in a cheap, soft cloth case - and can argue to what extent things should be well-packed.

And while theft by baggage handlers is not an everyday occurrence, it does happen occasionally.

This should be dealt with in the exact same way as damage, but may be harder to prove if the device is simply missing.

An airline may dispute the claim, and refuse to accept responsibility.

What about lithium-ion batteries - aren't they dangerous?

Asked by readers Louise, and Adam Gorbutt

Lithium-ion batteries are used in many rechargeable consumer electronics, from phones to large laptops.

It's true that the International Air Transport Authority (IATA) has released recommendations on transporting the batteries in the hold, and their US counterpart banned them as cargo.

The US ban was based on fears that cargo holds might not contain a possible fire from a bulk package of many batteries.

The IATA's 2017 guidance, however, says that any battery up to 160Wh rating should be fine - so long as it's packed in equipment.

That should cover all reasonable laptop batteries. But the operator's approval is required for these battery sizes - which may explain why you were asked to keep it in your hand luggage.

Also, it's important to note that spare batteries are not permitted in checked baggage - which includes "power banks" for recharging phones.

Why is the hold any safer than the cabin?

Asked by Mark Lucas, Helen, Paul, and Talal Burshaid

It's true that there are already very strong screening processes in place.

"I spent most of yesterday trying to make sense of the measures," Matthew Finn, managing director of security consultancy Augmentiq, said.

He said the possibility of an automatic trigger means any potential bomb need not be with the bomber "so I can't really understand why that distinction is being made between the cabin and the hold baggage."

A baggage handler at United - which is not affected by the new rules

But Philip Baum, editor of Aviation Security International, told the BBC: "Inside the cabin, the terrorist, or duped passenger, can at least be guaranteed a seat next to the fuselage - as on Daallo Airlines last year - improving the chances of destroying the aircraft."

"Always, you separate the bomber from the bomb - that makes people in the cabin a lot safer," said Sally Leivesley, a risk management expert.

"I think this is a very smart move and, actually, it's a little bit overdue.

"The fact that a very small device next to the skin of an aircraft, in the cabin, can cause massive depressurisation - it's certain death for everyone on board," she said.

She also said that screening of checked luggage had improved over the past several years, and it is possible to detect these devices.

- Published21 March 2017