Is child care the answer to Hollywood's gender gap?

- Published

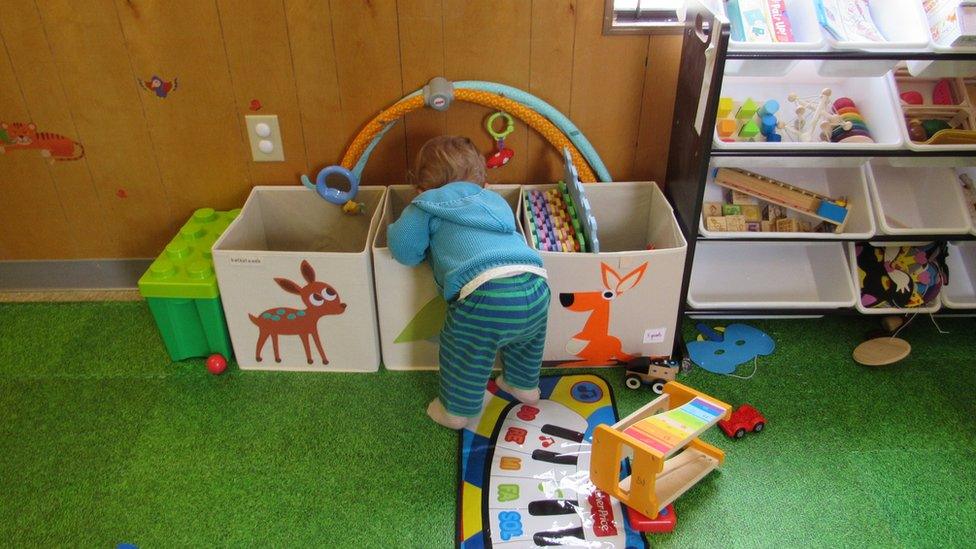

A young child playing at a Wee Wagon

Mothers who make movies say the answer to increasing the number of women in the film industry is simple: Hollywood needs childcare on-set for the directors, writers and others who work on location and for long hours.

So two women filmmakers are starting a business to do just that.

If there was a childcare on every film set and at every film festival, the number of women working in the film industry would not be so dismal, says Mathilde Dratwa, the New York-based filmmaker who created the Wee Wagon Project.

"You can't promote gender equality and not think about motherhood and childcare," says Dratwa.

Many studios already have on-site childcare centres, but they are for full-time studio workers, not directors, writers, cinematographers and other members of the cast and crew who come temporarily to work on a specific project.

And plenty of films work for weeks away from Los Angeles.

Dratwa's idea to fix the gap: Wee Wagons - mobile playrooms with soft padding, toys, changing tables and quiet corners for breastfeeding and napping. The trailers can be brought to any set, much like craft services takes care of meals.

Hollywood "makes so much work and happen for stars - they can make this work," she says.

Christy Lamb (left) and Mathilde Dratwa (right)

Dratwa tested her concept at the South by Southwest festival in Austin this month. She parked a Wee Wagon behind a theatre there and invited filmmakers to drop off their children so they could attend screenings or parties.

The Wee Wagon was available to everyone from directors to dolly grips, as long as they had a credit in a film at the festival.

Christy Lamb, the project's director of strategy and development, has a 12-month-old daughter. She considers the project a mission to make the world of film a better place.

"If you don't hire women or diverse people on your cast and crew, it shows on the screen," she says.

"It may not be obvious but it shows up on screen. And now that I have a daughter it's imperative. The heat is on. This has become a priority."

In 2016, women accounted for just 17% of those working behind the scenes on the top 250 domestic grossing films, according to the annual Celluloid Ceiling report, external.

Of those films, 92% had no female directors, 77% had no female writers, 79% had no female editors and 96% had no female cinematographers.

The numbers are grim in an industry under pressure to diversify. But motherhood is rarely part of the conversation in Hollywood, unless you count magazine stories about actresses shedding their baby weight after childbirth.

"I don't think Hollywood understands how deeply connected this is to motherhood," says filmmaker Foster Wilson, whose five-month-old played in a Wee Wagon while she attended screenings.

Wilson, an actress who is moving into directing, says she hadn't planned to come to the festival, but changed her mind when she heard there would be free childcare.

She also knew the child minders because they came from Collab&Play, a Los Angeles co-working space with childcare that's popular with filmmakers.

"It would be incredible to me if I were on set and there was childcare on set. It would be a total game-changer," she said.

"Do I want kids or do I want to get into the film industry? It's really difficult to do both.

"It's liberating to think it's possible."

It's possible, but not simple.

For one, the wheels make the wee wagons too expensive to insure, so trailers must be unhitched before any children get on board.

Convincing studios and independent productions to include childcare in the production budget also won't be easy.

In the competitive world of Hollywood many employees don't advocate for child care or other amenities that might brand them as "difficult".

But if Hollywood executives are serious about increasing the number of women in film, these mothers say they need to take childcare seriously.

The service is meant for women behind the scenes, but even Hollywood megastars like Reese Witherspoon or Angelina Jolie who can afford private nannies would benefit, says Dratwa, because the Wee Wagons would be childproofed and tailored for children.

Even a megastar's kids would have a better time in this wagon than hanging out in mom's trailer, Dratwa says.

While the filmmakers would still work long hours that are conventional in Hollywood, they could see (and breastfeed) their children on breaks.

Dratwa and Lamb hope to offer different models of Wee Wagons and create a non-profit arm, funded by grants, so independent films can afford the service.

Aspiring director Wilson hopes she can "budget the baby" on future films she directs.

"If we can make this mobile unit available, I would be a proponent of that on any film that I worked on."