Trumplomacy: What happened to State Dept press briefings?

- Published

Testing testing... is Rex Tillerson hearing the press corps' concerns?

During this week of mounting civilian casualties in Iraq and Syria, I felt the absence of the State Department press briefing.

The Pentagon spoke about the issue at various times in various venues.

But I was reminded of the bombing of Aleppo late last year.

Every day on camera we had a chance to grill the State Department spokesperson about what the US was, or wasn't doing, to protect civilians.

Then the blame was on Russian and Syrian warplanes, now it's on US airstrikes.

But now, without a public, daily briefing watched closely by foreign governments and US diplomats alike, the exposure is different.

Ten weeks into the Trump administration, the State Department is still vetting a spokesperson.

Mark Toner, a career foreign service officer, stepped into the breach for three of them.

He is now preparing for another assignment, although he may return to the podium briefly before he takes it up.

To be fair, the slow pace of staffing under this administration has affected all government departments, not just State.

And it's been slow before: Richard Boucher, who served as a spokesman or deputy spokesman in six administrations, said he briefed until May during the transition from George HW Bush to Bill Clinton.

But it's not just the lack of a spokesperson: it's the cutting back of briefings when they are provided.

There are only two on-camera briefings a week.

It's the reduction in the size of the diplomatic press corps allowed to travel with the Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson.

It's the secretary's own reluctance to speak to the public.

That's shaped partly by his personality, partly by his experience in the corporate world, and partly by the current flux in policy formation: he argues that when he has something to share, he will share it.

Even so, Mr Tillerson's aversion to the press has perplexed veterans of the foreign policy establishment, both Democratic and Republican.

"I don't understand (it), exactly," George Schultz, who served as secretary of state in the Reagan administration, told CBS' Face the Nation recently.

"He must have had some good reason for that."

But he added that reporters help communicate a secretary of state's vision to the world.

It's this aspect that worries Mr Boucher, more than the absence of a spokesperson, or any innate dislike of the press Mr Tillerson and his advisors may harbour.

"They don't understand how to make policy in a modern world," he says.

"Even in China you've got to work the public angles.

"Making and explaining policy are intimately linked."

Shy Melania braves spotlight for women of courage

A chance to see reclusive US First Lady Melania Trump helped fill the hall to capacity at a State Department ceremony on Wednesday.

In a rare public appearance, she helped present awards to 13 women from around the world recognised for demonstrating courage and leadership, often at great personal risk.

A few journalists sitting to my left told me they probably wouldn't have come if she hadn't been on the programme.

But the Colombian television reporter sitting to my right was more interested in the Colombian survivor of an acid attack, whose activism led to more hospital burn units and a tougher penalty for such crimes.

And the audience rose to give standing ovations for each of the women as they received their awards.

Mrs Trump was elegant, as usual, but rather stiff and awkward, clearly still trying on a role she didn't seek and doesn't seem to relish.

During a speech that made the case for women's empowerment she focused intently on two teleprompters flanking the podium, turning her head from side to side without making eye contact with the audience.

It would have helped had her text been less peppered with clunky jargon, over which she stumbled numerous times.

Trump crouched for photos with Botswana's Malebogo Molefhe

During the presentation of awards there were two moments when I thought she seemed to let down her guard just a bit.

One was with the honoree from Botswana, Malebogo Molefhe, who's an advocate for female victims of violence.

Ms Molefhe was in a wheelchair having suffered a brutal attack from an ex-boyfriend, and Mrs Trump crouched down to her level for the official photograph.

She also seemed to me more at ease when engaging with a Syrian nun who was recognised for her work with people displaced by that country's conflict.

Perhaps we will see more cracks in Mrs Trump's famous reserve as she prepares to move to Washington from New York, where she has been waiting out the end of her son's school term.

She is taking part in a number of events here this week and has just announced the hiring of a communications director.

Perhaps with time and practice she will find a voice of her own.

Or perhaps she will continue to avoid the spotlight that her husband is so very happy to fill.

Is Trump actually good for Nato?

Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg (R) with US Vice-President Mike Pence (L) in Brussels last month

Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg told me last week that his job has in some ways been made easier by US President Donald Trump.

That's because Mr Stoltenberg had already been pressing Nato members to pay their fair share on collective defence.

Now "the very clear message" from President Trump has put the issue "even higher on the agenda", he said.

This will be the main topic when Mr Stoltenberg visits the White House on 12 April, along with ways to refashion the Cold War alliance for the fight against terrorism.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson will be beating the same drum on Friday in Brussels.

Five Nato members currently meet the target to spend 2% of their economic output on defence, and everyone else has promised to do so by 2024.

But Mr Tillerson will push them to present a clear plan on how they'll do that, and to do it faster.

A senior State Department official added: "Absolutely no apology about that."

Defence Secretary James Mattis has said the US might moderate its support for Nato if there isn't a fairer sharing of the burden, but he's given no details.

Neither did the official. "Our joint security requires it," he said when asked about Mr Tillerson's leverage, noting that the "trend line is up" on increased defence spending.

Europeans have been rattled by Mr Trump's sometimes hostile rhetoric about Nato, not to mention his apparent ignorance about the alliance.

His Twitter claim that Germany owed Nato and the US "vast sums" of money for defence elicited a sharp rebuke from Germany's Defence Minister, Ursula von der Leyen, who noted tersely that "there is no debt account at Nato".

"He's not only critical of Nato, he doesn't seem to understand how it works," marvelled Jorge Benitez, director of NatoSource, a website covering news about the alliance.

Mr Trump was more diplomatic today: the White House said he had called German Chancellor Angela Merkel and told her he looked forward to attending a G20 summit in Germany in July.

He'll also be at the Nato summit in Brussels in May.

And his administration has supported the tiny Balkan state of Montenegro's accession to the alliance. It will be present on Friday as an invitee, the State Department official told me.

The kerfuffle over Mr Tillerson's initial decision to skip the foreign minister's meeting has been explained as a scheduling conflict.

Senator John McCain attributed this to the top US diplomat's skeleton support staff: "You can't expect the secretary of state to conduct all his calendar appointments."

The rescheduled event means Mr Tillerson will be able to meet his Nato allies before he visits the alliance's principal challenger, Russia, later in the month.

British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, on the other hand, has had to cancel a Friday visit to Moscow to make the new Nato date.

This is a bit awkward since the invitation came from Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov.

But perhaps also a happy coincidence for the Foreign Office that Mr Johnson can avoid engaging with the Kremlin so soon after mass arrests during protests led by opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who was jailed.

State Dept's baffling jargon on Syria

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has casually dropped a loaded phrase into the confusion about President Trump's plan for defeating the Islamic State Group.

The US, he said last week, would work to establish "interim zones of stability" in Syria to allow refugees to return home.

His words brought to mind the debates within the Obama administration about safe zones. Those would have involved patrols by US warplanes to deter the Syrian air force from bombing civilians and rebel forces.

President Trump, on the other hand, has promoted the notion of safe zones as a way to stop the tide of refugees pouring into Western countries, though without providing details.

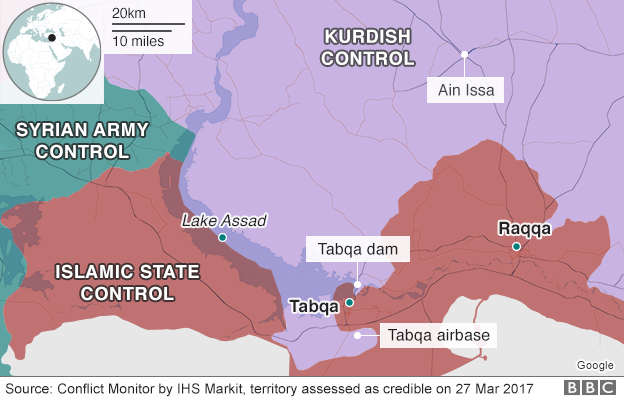

Today a senior State Department official fleshed out the phrase a bit. He said the Americans had in mind pockets of stability in Syria's two conflicts: areas where coalition forces had defeated Islamic State militants, and areas where ceasefires could "de-escalate" the civil war.

The latter, he said, were being negotiated by Turkey, which backs some opposition groups, and Russia and Iran, which back the Syrian government, at talks in Astana, Kazakhstan.

He said the coalition would look for ways to reinforce any such areas of stability to make them safe for civilians, especially near the borders of critical allies: Jordan in the southwest, and Turkey in the northwest.

The official talked only of US humanitarian, not military support. But some sort of holding force would be necessary to secure the zones.

Recently America's top military officer in the Middle East, General Joseph Votel, said safe zones are a viable option in Syria where areas have been secured, but he didn't say who would secure them.

More likely he would have had US-trained forces rather than US troops in mind.

The coalition has had some success at stabilising areas liberated from Islamic State militants in Iraq, and wants to transfer that model to Syria.

But Syria is a much more complex war zone with no government partner, conflicts even between US allies, and peace talks bedevilled by collapsed ceasefire agreements.

So at this stage, the "interim zones of stability" are more of an idea than a plan.