The Americans volunteering to watch executions

- Published

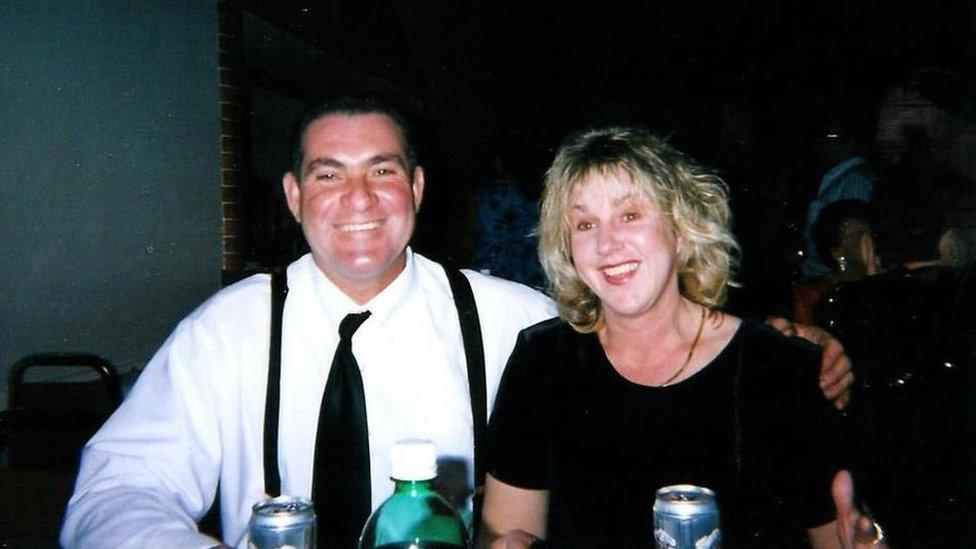

Teresa and Larry Clark, from Waynesboro, VA, have witnessed multiple executions

Teresa Clark has watched three strangers die. She held her husband's hand the first time, but after that the experience began to feel normal.

The couple, who run a chimney sweeping business in Waynesboro, Virginia, volunteer to watch executions. Teresa's husband, Larry, 63, went to the first one alone.

"He was very curious. I dropped him off and I asked him all kinds of questions," she says. "Afterwards he said, 'You gotta see this'."

Eventually she did. In 1998 they made the "nervous journey" to watch the execution of Douglas Buchanan, Jr, who had been convicted of murdering his father, stepmother, and two stepbrothers.

Witnesses like Teresa and Larry Clark are a legal necessity. In Virginia, as well as some other death penalty states, the law requires people with no connection to the crime attend each execution.

Volunteers "are considered public eyewitnesses, and go to executions standing in the place of the general public," says Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center.

"It's a recognition that these proceedings need to take place in public view."

On the night of the execution, Teresa, Larry and the other volunteers were picked up by the prison bus and taken to Greensville Correctional Facility in Jarratt, Virginia. After spending some time mingling with reporters in the cafeteria, they were led into a small room.

The room was brightly lit, and featured a large viewing window. When the curtains opened they saw the gurney. Then Buchanan entered.

When asked if he had any final words, he replied: "Get the ride started. I'm ready to go."

During executions, Teresa says the prisoners look right into the observation gallery, and the room stays silent.

"It's quite weird, watching somebody look at you as they're getting ready to die," she says.

After the execution, the doctor pronounces the inmate dead and the curtains close. The witnesses are thanked for their service and sent home.

The volunteer process made headlines recently when Wendy Kelley, director of the Arkansas corrections department, appealed for volunteers at a community meeting. The state plans to execute a record seven inmates in 11 days, but can't find enough people who are willing to watch.

Arkansas state law says that at least six "respectable citizens" must be at every execution to "verify that the execution was conducted in the manner required by law."

The publicity worked. Arkansas now has a flurry of volunteers.

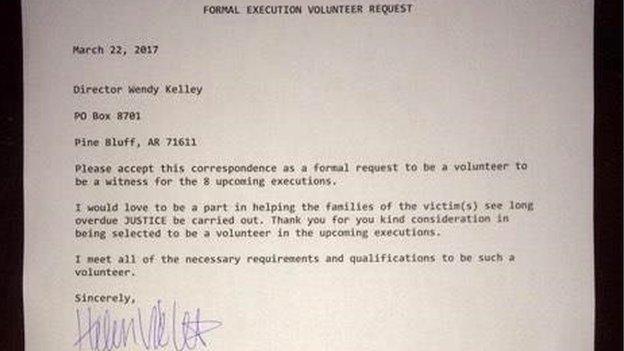

Beth Viele, 39, from Jacksonville, Arkansas, wrote a letter to Kelley expressing her interest.

"Please accept this correspondence as a formal request to be a volunteer witness for the eight upcoming executions," she wrote.

"I would love to be part in helping the families of the victim(s) see long overdue JUSTICE be carried out."

Beth Viele's application letter to serve as a volunteer witness

Frank Weiland, 77, works as a brass works fabricator in Lynchburg, Virginia. He's volunteered to witness four executions. He says he goes as a show of support for law enforcement.

The last execution he witnessed was in 2006, when Brandon Hedrick chose the electric chair over lethal injection.

"This guy didn't live too far from me, and I know some people that knew him."

"They said he was scared of needles," Weiland says with a laugh.

He watched Hedrick get strapped into the chair, and saw the warden put a sponge on his head to help the electrical current travel faster. "The next thing you know - boom!" Weiland says.

"I noticed his hands on the arms of the chair, and I said, well if there's anything as far as feeling goes he'll clench, and he did not clench. The noise is kind of a bump.

"He didn't convulse or anything. As a matter of fact if I had the choice I would take the chair.

"The only thing that told you that he was getting it was the way his legs smoked a little bit."

Eight men the state of Arkansas originally planned to execute over 11 days. Jason McGehee (bottom left)'s execution has been stayed an additional 30 days

Still, witnessing these deaths leaves an impact.

"I've replayed it very much in my mind," he says. "I really don't know why, but I have."

Teresa Clark tells a story about the night following the first execution she attended.

"I was sitting in my car at a red light and I looked in the rear view window, and I swear I saw the man I just saw die," she says.

"The picture kind of sticks with you."

But she remains undeterred.

"If they called now and needed somebody, I would go."

"It came across my mind, and it still does, that these people know when they're going to die, and the people they killed didn't. They get to say their goodbyes, so I really can't say I felt sorry for them."