Trump’s lack of clarity on foreign policy may prove catastrophic

- Published

The lack of clarity with US foreign policy is a cause of concern for America's allies

Just a few days ago the Russian embassy in London responded on its Twitter feed to the British Foreign Secretary's announcement that he was cancelling his planned visit to Moscow.

Accompanying the Russian tweet was a picture of the Charge of the Light Brigade during the Crimea War - one of the great disasters of 19th Century British military history.

It was, though, a curious choice of subject.

Maybe the Russian embassy should brush up on their own history, for whilst the charge itself was a glorious failure, Britain and France - who had gone to war with Russia ostensibly over an arcane dispute involving the Ottoman Empire and access to holy sites - did in fact win and Moscow had to back down.

But there is another more important lesson from the Charge of the Light Brigade that is relevant to today's diplomatic crisis. The flower of Britain's Light Cavalry charged down the wrong valley directly into the mouth of the Russian guns because the message ordering them into action was not clear.

The US struck at the Syrian airfield from where the Americans say the recent chemical attack was launched with impunity. They did so to reinforce a red line - drawn by the previous Obama administration - but one never acted upon.

Of course the thing about red lines is that they need to be crystal clear. In the immediate aftermath of the strike this seemed to be the case. The message was: use nerve gas again and consequences will follow.

But on Monday, White House press secretary Sean Spicer muddied the waters.

Asked if air attacks with conventional weapons might also draw US punitive action, he said: "If you gas a baby, if you put a barrel bomb into innocent people, you will see a response from this president."

Barrel bombs, though, tend to be large canisters filled with explosives and shrapnel that are typically dropped by Syrian government forces from helicopters. In other words they are conventional rather than chemical munitions.

So was Mr Spicer broadening the red line? Belatedly the White House had to issue a clarification noting that what he really was saying was that barrel bombs containing chemical weapons would draw a US response.

This lack of clarity would not matter quite so much if it was not characteristic of the Trump administration's whole approach to foreign policy. And the stakes could not be higher.

One crisis in US-Russia relations is already upon us. Another involving the unpredictable North Korean regime is fast building. These are the Trump team's first big foreign policy tests and so far they are gaining a very mixed report card.

In the wake of the US strike on the Syrian air base, Trump administration officials - ranging from the Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley and US National Security Adviser General H R McMaster, to the White House spokesman Sean Spicer - have suggested a variety of US policy approaches that extend from the relative isolationism of "America First" to a more strident interventionism.

On key questions there seems to be little agreement.

Is the US eager to remove the Assad regime? Does its priority remain the fight against so-called Islamic State? How does the strike against Syria that has enraged not just Russia but also Iran square with US interests in Iraq, where, unlike in Syria, Washington and Tehran find themselves on the "same side" in that they are both giving military backing to the Iraqi Government?

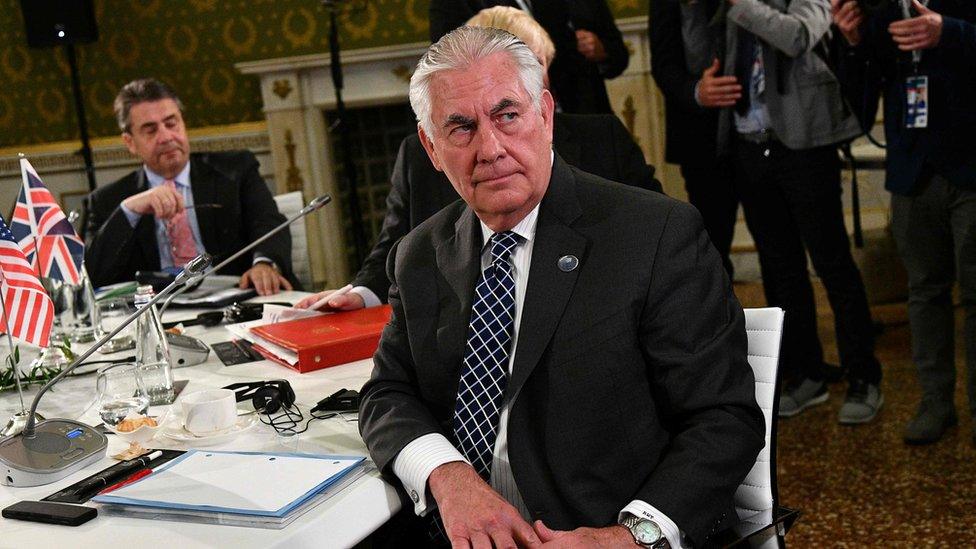

Mr Tillerson will arrive in Moscow without the backing of the G7 for economic sanctions against Russia

The lack of clarity in the message is hampering America's allies as well.

The British Prime Minister Theresa May has spoken of a "window of opportunity" to separate Russia from Syria's President Assad. But Tuesday's G7 group of nations meeting has pointedly failed to agree on the need for additional economic sanctions against Russia.

Mr Tillerson is arriving in Moscow without the strong backing from America's key allies that he had hoped for. Yes, they all agree that Mr Assad cannot be part of the solution. They all agree Russia must exercise its responsibilities in Syria. But in terms of what to do, they are as much at sea as the Trump administration itself.

What is still needed is a broad statement of US policy goals and the instruments that will be used to achieve them. Without that the growing militarisation of US foreign policy - stepped up strikes in Yemen; more troops to Syria and Iraq; and the punitive cruise missile attack in Syria - may worry both friends and potential enemies alike.

There seems to be no central guiding brain behind the evolution of the Trump team's foreign policy. The US president himself has failed to articulate any clear approach.

With regard to Syria that may be unsettling. With regard to North Korea, it could be potentially catastrophic.