Fatally flawed: The loopholes that let domestic abusers keep their guns

- Published

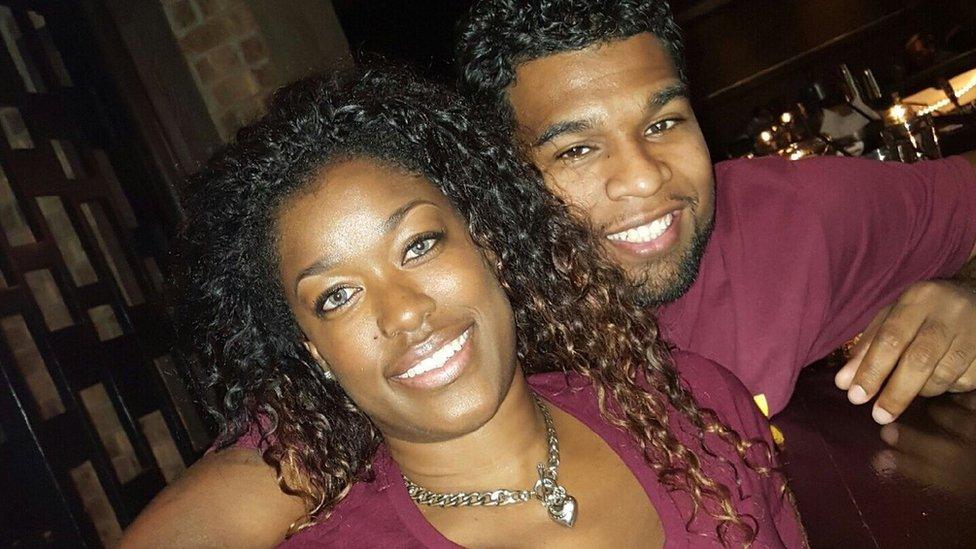

Chinika Hursey and her boyfriend were murdered as they lay in bed

In late February in Baltimore, 36-year-old Chinika Hursey petitioned a court for a domestic violence protection order against her estranged husband, Dominick.

In a detailed handwritten account she described a violent physical assault at a car dealership in the city.

Police served Dominick with the order in late March, instructing him to stay away from her home and surrender any guns. He said he didn't have any. Without a warrant they couldn't search the house, so they left.

A week later he broke into Hursey's home while her children slept and shot her and her boyfriend dead as they lay in bed.

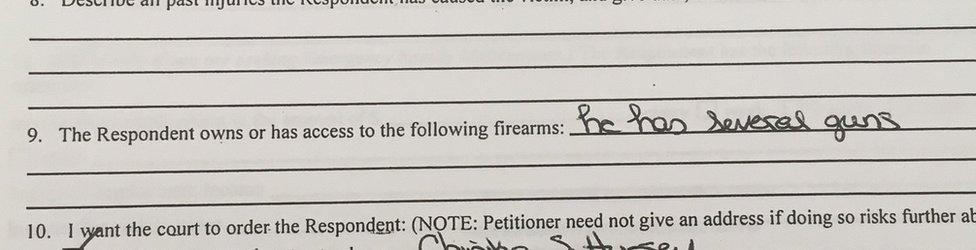

"I fear for my life and that Dominick will try to kill me," Hursey had written in her petition to the court back in February, adding: "He has several guns."

Dominick Hursey is accused of killing his estranged wife

More than 50 women in the US every month are killed by former partners, and the presence of a gun in a domestic violence situation makes it five times more likely that a woman will be killed, according to data compiled by gun safety group Everytown.

The latest high-profile case came on Monday, when Cedric Anderson shot dead his estranged wife and an eight-year-old child at a San Bernardino school. According to police, Anderson had a history of domestic violence.

In case after case of multiple-victim shooters, police have found previous accusations or convictions of abuse. Orlando nightclub shooter Omar Mateen, Dallas police killer Micah Johnson and Planned Parenthood gunman Robert Dear are just three in a long list.

But the vast majority of cases don't make national headlines, and legislation designed to keep guns out of the hands of domestic abusers has major flaws that are putting lives at risk.

Chinika Hursey notified the court that her estranged husband owned guns

A domestic violence conviction or restraining order will turn up on a federal background check and prevent a gun sale, but there are no federal laws requiring convicts to surrender guns they already own. Only 30 states authorise or require confiscation in the event of a protection order, according to a recent report by the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence, and application of the law varies wildly.

An Everytown study of cases in Rhode Island between 2012 and 2014 showed that only 5% of people issued with a protection order were ordered to surrender their guns. In cases where there was a written record of a firearm threat, that figure rose to just 13%.

In Baltimore, police ran a check to see if Dominick Hursey owned any weapons but it didn't pick up a handgun he had purchased in Pennsylvania. The kind of national gun registry which would have alerted the Baltimore officers to the purchase is fiercely resisted by gun rights activists.

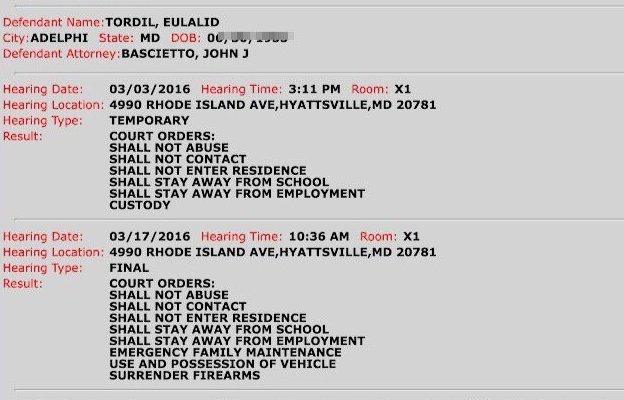

In March of last year, in Maryland, science teacher Gladys Tordil obtained a domestic violence protection order against her husband Eulalio. He was instructed to surrender his guns and he handed over at least 10, but he kept one, which he'd bought in Nevada.

Weeks later he used it to shoot 62-year-old Tordil dead outside her school, in front of one of her daughters. The following day he shot four more people, killing two.

An excerpt from a protection order against Eulalio Tordil shows he was ordered to surrender firearms

Of the 30 states that have some law authorising the confiscation of guns following a protection order, only 11 require the guns be handed to police. Some states allow firearms to be sold to a licensed dealer. Nine states allow guns to be handed over to any third party not prohibited from possessing a gun.

"There's a lot of room for improvement on the possession side," said Shannon Frattaroli, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health who studies gun use in domestic violence.

"Some states place deadlines on surrendering guns and require some kind of proof presented to court. Some simply say you can't possess a gun but don't take any steps to enforce it. They're essentially relying on goodwill," she said.

Kelly Roskam, from the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence, described the existing collection of laws as "useful but flawed".

"In states that require guns to be turned over to police, someone might hand over six, seven, eight guns. But they only need to hang on to one."

Some states allow abusers to sell their guns or give them to a third party

In states that require background checks, 38% fewer women are shot to death by intimate partners, according to data compiled by the Department of Justice and FBI.

But even in states that require a check, there are always loopholes. In 2012, Zina Daniel obtained a domestic violence protection order against her husband in Wisconsin, which should have prevented him buying a gun. But he bought one online, from an unlicensed seller.

The next day he shot seven people, killing three - Daniel and two of her colleagues.

One solution being explored by California and Washington takes the kind of protection order obtained by Hursey, Tordil and Daniel and focuses it specifically at guns.

The gun violence restraining order allows partners and, for the first time, family members to seek to have gun purchases and ownership restricted. It can be issued for 21 days for an emergency situation or up to a year in the event of a more substantive order.

Factors taken into account by a judge include recent acquisition of a gun, threats or acts of violence, and substance or alcohol abuse. "These orders should lead to better enforcement," said Ms Frattaroli. "But they are only in two states."

Science teacher Gladys Tordil was shot dead in front of her daughter

And even with a gun-specific restraining order, the risks remain.

The weeks after someone decides to leave an abusive partner are the most dangerous, said Ruth Glenn, executive director of the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, "and that is magnified by the presence of a gun".

"Protection orders are a piece of paper," she said. "They are one part of being safe, but we say please don't rely on them as your only protection."

For victims afraid of gun violence, a plan should begin with keeping a mental or physical record of what weapons an abuser has and where they are, she said. That can help obtain a warrant to search a property.

Chinika Hursey told the court that her husband had guns, but it was not enough in her case. She fell through one of the many cracks in the law.

"Woman and children will remain at risk every day until our system figures out how to uniformly keep guns out of the hands of abusers," Ms Glenn said.

You can contact the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1 (800) 799 7233. Other national domestic violence hotlines can be found here, external.

- Published11 April 2017

- Published5 January 2016

- Published20 December 2016