The man who catches marathon cheats - from his home

- Published

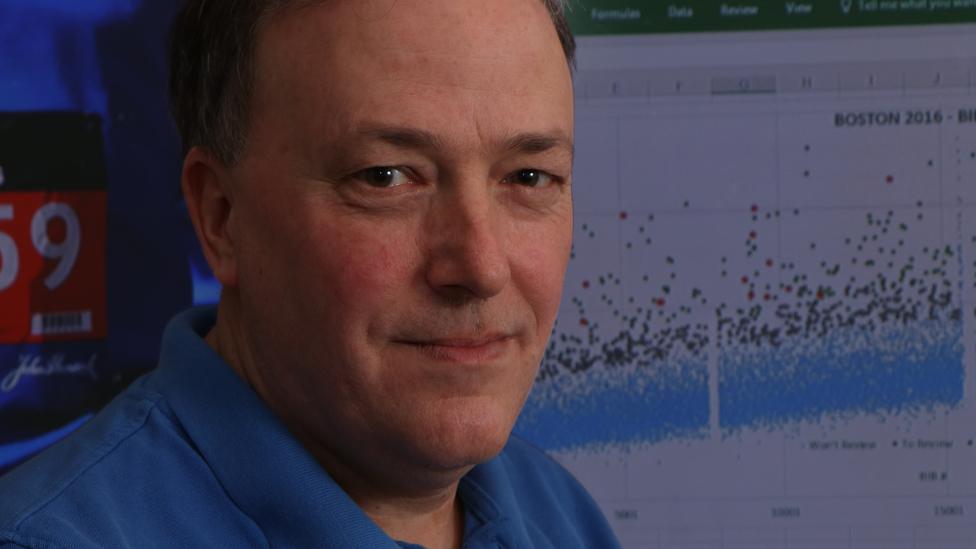

Boston Marathon runners start their 26.2 mile journey in 2016 - Derek Murphy is looking for cheaters among them

For months, a runner named Cindy posted motivational photos on Instagram and Facebook, chronicling the miles she put in to prepare for the New York Marathon.

When the big day came, she posted about the gear, the energy gels, and the coconut waters that would sustain her through the 26.2 miles (42.1km)

Cindy ran the race of her life, finishing the New York Marathon in just 3 hours 17 minutes and 29 seconds - a lot faster than her pace in previous half-marathon finishes, which each took a little over two hours.

"Ran my heart out today and left everything on the course. All the training paid off and qualified for the Boston Marathon!" she posted on Instagram, along with a post-race selfie and a photo with the finisher's medal.

But Cindy's incredible marathon time seemed just a little too incredible to a man sitting at his computer nearly 640 miles away.

Derek Murphy, a former marathoner and business analyst who lives outside Cincinnati, has made a name for himself exposing marathon cheats on his blog, Marathon Investigation.

During his racing days, he frequented online message boards about big races, which occasionally featured a high-profile cheating scandal.

"There was so much tension from those specific cases, I just wondered how many other people cheated," he said.

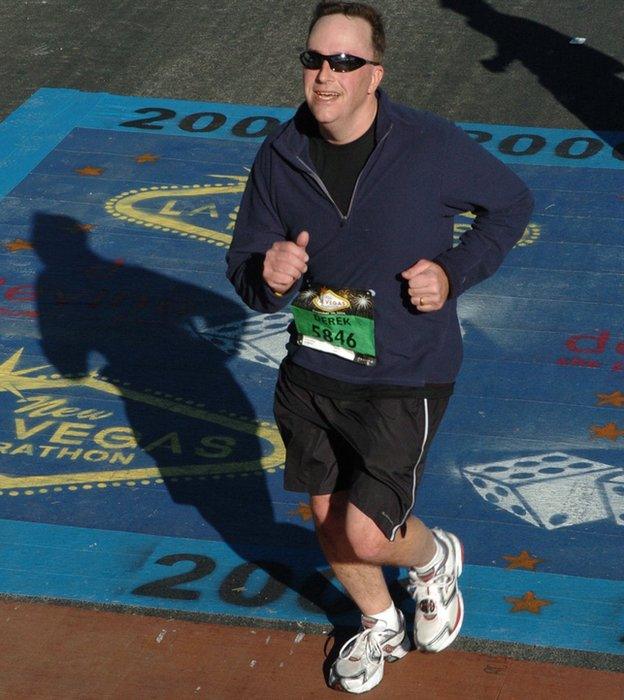

Murphy is a former runner himself

Murphy's investigative process has evolved since he first started looking at race results.

He has gone from looking at missed split times in public race results to peering into other clues like suspiciously fast race times, starting line and finish line photos, and bystander video footage recorded at races.

When Murphy heard about Cindy's speedy personal record, he started scrolling through the New York race photos looking for evidence that she had honestly run her improbably fast race.

He didn't find any photos of the petite brunette running on the course. However, he did find a photo of a tall, athletically-built man running with Cindy's bib pinned to his shirt.

After Murphy sent the photos and Cindy's former half-marathon times to the New York Marathon organisers and published a story on his blog, external, Cindy was disqualified.

She is one of about 30 runners identified by Murphy who sought entry into the 2017 Boston Marathon using fabricated times.

At least 15 of those runners were disqualified from showing up at the starting line in Hopkinton near Boston when the starting gun goes off on Monday.

Some of the remaining 15 might get to run the race, but their results will be closely scrutinised. Murphy expects to identify many more people who cheated to get to Boston after the race is completed.

Only the fastest amateur and elite runners can earn a spot in the iconic Boston Marathon.

Men under 35 need a finish better than three hours and five minutes in an earlier marathon to earn a spot. Women under 35 have 30 extra minutes.

While around 30,000 people are fast enough to run the marathon each year, more than 4,500 qualified runners were turned away in 2016 because too many people registered for the race.

"The integrity of the sport is enormously important to us, and to the athletes who run in our races," said a spokesperson for the Boston Athletic Association in an email statement.

"When it comes to qualifying for Boston, we rely on the race organisers and timing systems they employ to produce accurate results, and we also rely on the honesty and integrity of 99.99% of competitors who compete fairly in pursuit of their personal records."

Murphy said he thinks the actual number of cheaters is probably higher than the 0.01% cited by Marathon officials - which would be just three people - but he thinks it is still a small percentage.

Finding those rare cheats can be tough.

"There's no governing body for marathons per se to look at results," Murphy said. "Most of the time race timers and directors definitely do care, but there's a lack of resources."

Cheating in a marathon can come in many forms. Some cut a few miles out of their qualifying race. Others give their racing bib to someone a bit faster. In rare cases, people pay to have their results altered.

Most races have methods in place to detect the most obvious examples of cheating. The race bibs have tracking devices that log a runner's split time at mats placed strategically throughout the course.

Sometimes missed mats and unbelievably quick splits will alert race officials to the foul play. But cheaters often slip across the finish line and into race results unnoticed by race timers. Some of these people claim amazing times - good enough to get into Boston.

Mr Murphy has caught cheats by looking at the distances displayed on GPS watches in finish line photos and by matching finish times with time stamps on video recordings of races.

When a runner whose qualifying time places them in an early corral position at the Boston Marathon but finishes in the back of the pack, Mr Murphy marks their race result as a priority for investigation. Often, if someone's Boston time is much slower than their qualifying time they may have cheated in an earlier race.

Instead of looking back at runners after the Boston Marathon happens as he has in the past, this year Murphy tried to find people who cheated to qualify before race day. He hopes that more honest runners with qualifying times near the cut-off will be able to run the race because of his analysis.

Not everyone agrees with Mr Murphy's methods. On the Marathon Investigation Facebook page, external, sandwiched between encouraging comments, the occasional criticism pops up, taking the blog to task for going after amateur runners and giving them too much attention.

Crews install the decal marking the finish line on Boylston Street

Women's Running magazine published a critical opinion piece, external arguing that novice runners who cheat should not make the news.

Mr Murphy isn't always in the business of getting people disqualified from races. Sometimes, he does just the opposite.

Last year, Ryan Lee ran the London Marathon in just over four hours and 13 minutes, but after he finished a race official contacted him to tell him that he was disqualified for missing a timing mat. The race organisers thought he had cut the course.

One missed mat doesn't always mean someone cut a course - sometimes the mats don't cover the entire width of the course and a runner might accidentally run around it. But Mr Lee's time also seemed to be too fast - he appeared to catch up to runners who had started more than 15 minutes before him, very early in the race.

"It really was draining," Mr Lee said. "I raised quite a bit of money for my chosen charity and I put 110% into the actual marathon. To be then called a cheat after that really does make you feel distraught."

Mr Lee and his mother, Elizabeth Lee, set out to try and prove that he had run the entire race. They tracked down photos of Mr Lee on different points on the course and sought out other runners who had seen him race. But finding sufficient evidence to convince the race director that Mr Lee was innocent was difficult.

"I thought I would never be able to prove that I never did cheat," Mr Lee said.

Mr Murphy heard about Mr Lee's case and began to look at the evidence - video footage of the race, photos, and Mr Lee's split times - and he noticed that Mr Lee appeared with runners who had a start time about 15 minutes before the London Marathon claimed he had started racing.

Crucially, Mr Lee was photographed beside those other runners before race officials said he had crossed the starting line.

Mr Murphy used these photos to prove that Mr Lee had actually started the race much earlier, and ultimately run a race about 15 minutes slower than the London Marathon had recorded.

Derek Murphy - with his own proof of finishing a marathon

Even with the missed mat at the 10km mark, Mr Lee's results made sense if his start time had been recorded incorrectly. When the race was presented with all of the evidence, they reinstated Mr Lee's official race times.

Proving foul play on the race course often requires more than just number crunching. Mr Murphy said that Mr Lee's case is a great example of why he looks at more than just race times.

"I was able to vindicate somebody, but if I had just looked at the data, I would have thought he cheated," Mr Murphy said.

Mr Lee still runs, in part because his racing record was cleared. He is planning to run the 2017 London Marathon later this month.

"I would love the do the marathon in America and meet Derek to say thank you for all the help." Mr Lee said.

"Without the help, I would still be known as a cheat."