Maudie: Biopic of obscure painter becomes surprise hit

- Published

Maud Lewis's house, which she painted herself

In her lifetime, Canadian artist Maud Lewis sold her paintings door to door. Decades after her death, a movie about her life story is selling out theatres in her home province of Nova Scotia.

A compulsive painter whose local following grabbed the attention of the media well before the days of Instagram, Lewis spent most of her life in Digby County, Nova Scotia, in a tiny house that would serve as her studio, gallery, and even canvas.

Alan Deacon, a long-time collector who has now become the go-to expert on Lewis' work, remembers the first time he came to see her in her house a couple of years before she died. Lewis had painted almost every surface of the 12ft (3.7m) by 12ft house with pictures of flowers and leaves, from the walls to the shutters to even her pots and pans.

"It was an unbelievable experience to think that a place like this existed in our time," he told the BBC.

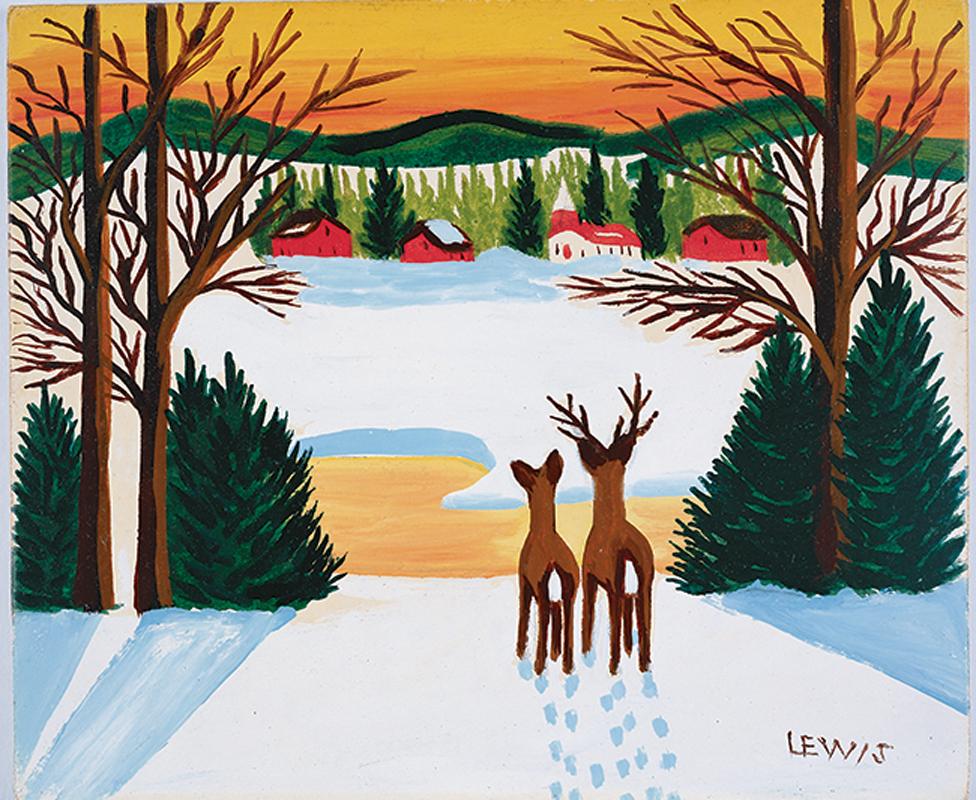

Deer in Winter, circa 1950 by Maud Lewis. Oil on pulpboard. Collection of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia

Now, a movie about her life and the discovery of a long-lost painting in a thrift store have renewed interest in this eccentric but charming painter.

Maudie, staring Sally Hawkins as the artist and Ethan Hawke as her husband Everett, is the second-highest grossing film at the box office in the Atlantic Canada region (number 10 in Canada overall), according to its distributer Mongrel Media.

You might also like:

Local theatres have been selling out of tickets and adding screenings, with one local indie cinema owner exclaiming that the film made a year's worth of profit since it opened nationwide three weeks ago. According to Mongrel, the film is even outselling the area's top blockbuster, the Fate of the Furious, per screen.

"When you find a story that really speaks to Atlantic Canada, Atlantic Canada loves to see those stories," says Mary Young Leckie, one of the film's producers. "They're their stories, and they don't see them that much,"

The film's success has also been spurred by a rather serendipitous find: an unknown Maud Lewis painting found in a thrift shop is being auctioned off for charity, with bids topping C$125,000 ($91,500, £70,685). The work was authenticated by Mr Deacon, a retired school teacher who is now somewhat of a Maud Lewis sleuth.

Over the years, he's amassed quite the collection but also learned how to spot the fakes - knowledge he says he'd rather keep a secret, so that con artists don't try and game the system.

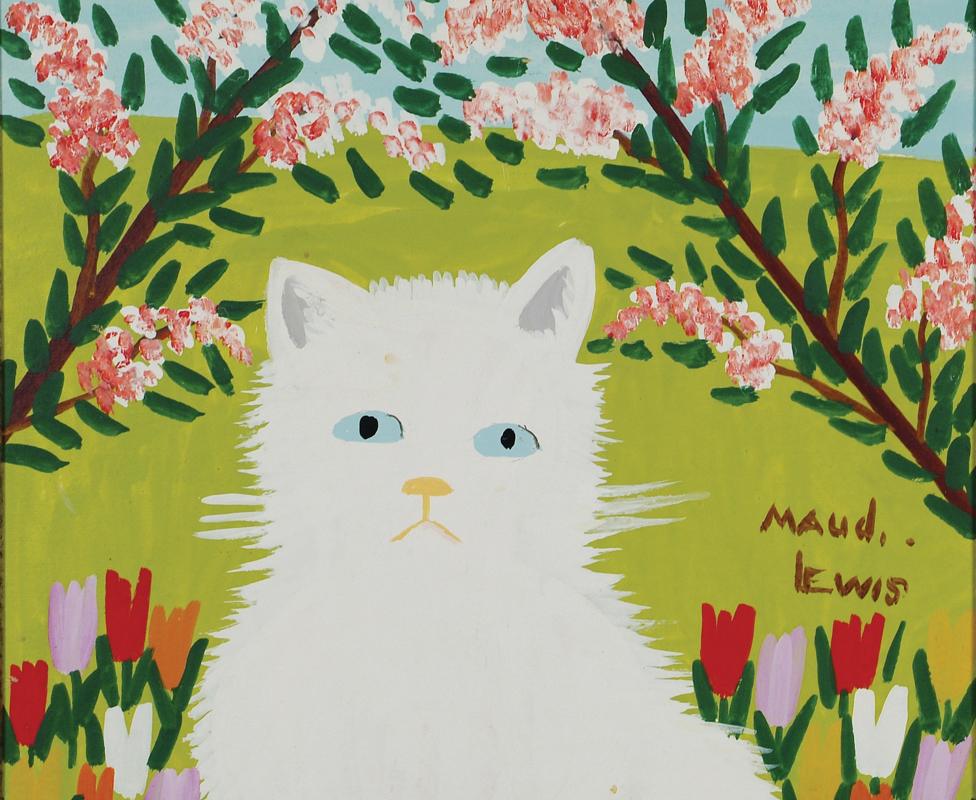

White Cat by Maud Lewis, circa 1960s. Oil on pulpboard. Gift of Johanna Hickey, Vancouver, British Columbia, 2006.

"At one point I thought, am I the only person out there buying these things? Because there really wasn't anyone else interested," he said.

Now, people call him weekly to ask him to authenticate a painting, or tell him what their painting might be worth.

Typically characterised as a "folk artist", Lewis was self-taught and lived her whole life in poverty. Unable to afford things like canvas, she'd paint on anything from scraps of wood and plywood to thick card stock. Her subjects were the things she saw in her everyday life - fishermen, wildlife, flowers and trees.

"Maud was not a person who travelled to other galleries or saw other art, so there's a kind of naivete to it," said Nancy Noble, director of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

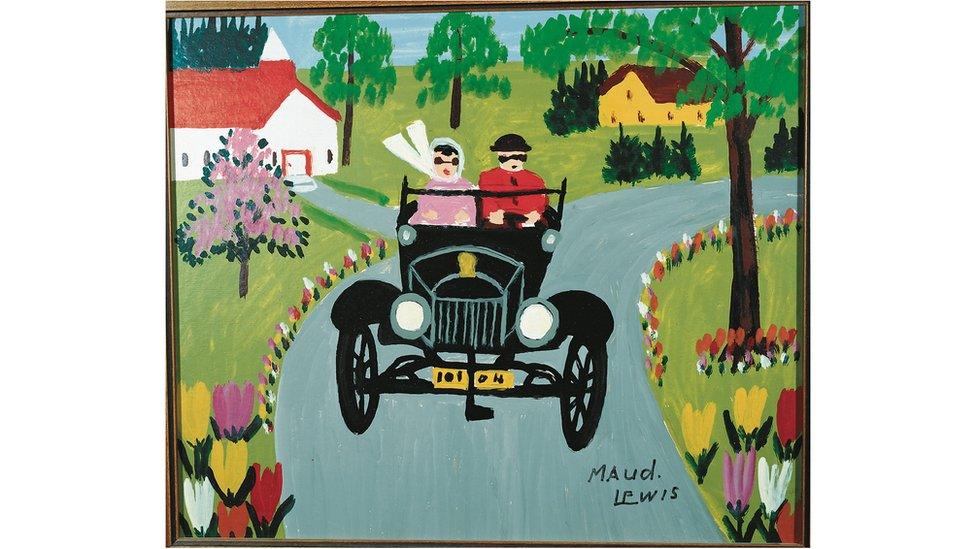

Model T on Tour, circa 1960s by Maud Lewis. Oil on graphite board. Collection of Dr Doug Lewis and Florence Lewis, Digby, Nova Scotia

Over the span of about 30 years, Lewis became known as a local celebrity. Debilitated by arthritis and later emphysema, she sold Christmas cards and paintings door to door with her husband, a fish peddler.

She gained national attention with a CBC documentary and a newspaper article titled "The Little Old Lady Who Paints Pretty Pictures". After that, Richard Nixon bought two of her paintings for the White House, but commercially, Lewis never had much success.

Like many great artists before her, it wasn't until after her death that her star truly began to rise.

Soon after her death, Mr Deacon noticed that her paintings began selling for $350, up from the $10 she charged when she was alive.

By 2012, paintings were going for about $20,000.

Her latest sale, a picture of a lobster fisherman, currently has a high bid of more than $125,000. The online auction closes 19 May.

Mr Deacon believes Maud's critical acclaim will continue to rise.

"The American art critic Clement Greenberg talks about how invariably in art, it is the tortoise that overtakes the hare. And she's very much the tortoise," he says. "As well known as she is today, I still think her day in the sun is yet to come."

- Published8 February 2017

- Published1 February 2017