How did the remote French outpost of St Pierre and Miquelon vote?

- Published

Pierre Fouchard (L) and Alex Bry (R) sitting atop Pierre's Peugeot overlooking Étang de Savoyard on Saint-Pierre island

Last March, just weeks before announcing her candidacy for the 2017 French presidential election, far-right politician Marine Le Pen set foot onto a craggy, frostbitten island 10 miles off the coast of the Canadian province of Newfoundland & Labrador. How did Le Pen's ideas resonate on the islands so far from the French mainland?

This was no foreign visit. The island of St Pierre, together with its larger but less populated neighbour Miquelon, is a remote outpost of France. It is the last French soil left in North America, and the oldest remaining French overseas territory in the world.

Few French people visit, or have even really heard of St Pierre and Miquelon, and that was exactly the point that Marine Le Pen, then leader of the Front National party, was trying to make when she arrived. Under her leadership, she argued, the people of St Pierre and Miquelon would be forgotten no more.

In the year since, the presidential election has been one of the most surprising in France's modern history, with far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon and mainstream-right candidate François Fillon being eliminated in the first round of voting. French citizens were left to decide between Le Pen and a heretofore unelected 39-year-old banker, Emmanuel Macron.

Le Pen may have lost the vote for president, but her message resonated in St Pierre. Macron, on the other hand, has demonstrated little familiarity with life in this particular corner of France.

Île aux Marins, part of the chain of islands comprising Saint-Pierre and Miquelon

"I will never vote for Macron," said Johann, a French fisherman and captain of the small scalloping vessel Emeline.

As the Emeline zips through the Bay of Fortune en route to the St Pierre harbour, a couple of dolphins race by on the port side.

"We need something new," he adds. "She - Le Pen - is not new either, but at least she is different, you know. Macron is the same."

Johann was born and raised in St Pierre.

Although he and his fellow islanders number just 6,000, their votes held a special significance in French elections. St Pierre and Miquelon is the easternmost of France's western territories (the others being in the Caribbean and South America), which voted a day ahead of mainland France. Consequently, the very first votes to be cast in any French national election are those from St Pierre.

In mainland France, the rise of Marine Le Pen and the far right generally spurred increasing concern around immigration and terrorism, along with dissatisfaction with the European Union.

For Johann and his fellow fishermen, these concerns are quite literally a world away.

They gauge politics by hunches and intuitions, and in that frame of mind, president-elect Emmanuel Macron seems like an elitist, someone who would be out of place on a scalloping vessel in the high Atlantic.

Saint-Pierre was founded as a fishing territory, but today fishing comprises only 3% of the economy. While the local government has made a huge effort to boost tourism, the high cost of getting to the islands means that they receive only 10,000 visitors a year. The bulk of economic activity comes from public spending and administrative work. In this context, it is easy to see why, among the fishing community at least, a change from the establishment would be most welcome.

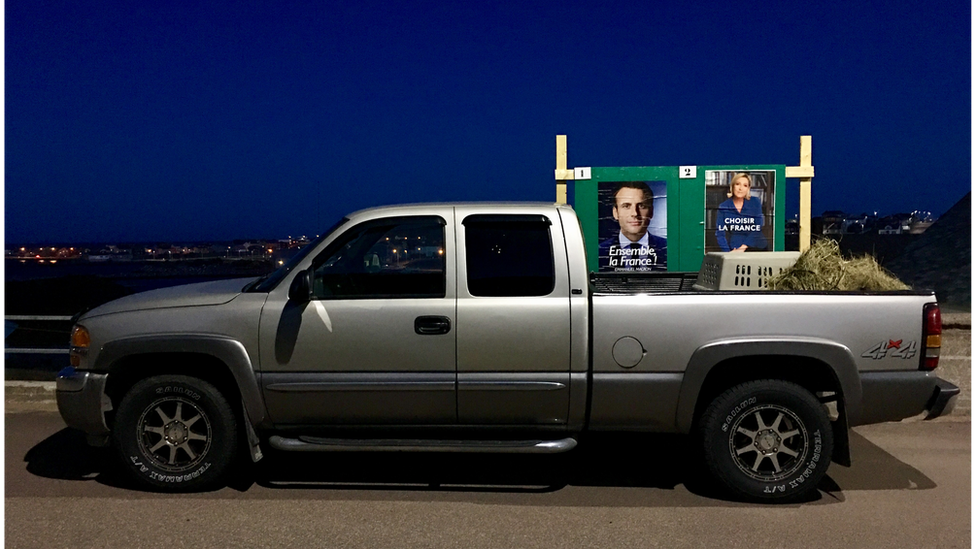

Election posters up in Saint-Pierre and Miquelon

On Thursday evening before the election, one of the bars in the island was packed with young people. In typical French fashion, the life of the party was in the smoking section - and there were plenty of opinions on the election.

One vocal group of friends in their late teens and early twenties had just ordered a round of shots.

They were a diverse bunch, including two young women from France proper and one from Corsica. The women are all living in St Pierre because their parents have been sent there for work. The young men are all natives of the island, though with their black skinny jeans and fashionable haircuts, anyone of them could have been transported from a Parisian street corner.

All but one supported far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon in the first round. It seems he won the youth of Saint-Pierre over with his leftward pivots and his use of YouTube and social media. Once Mélenchon was out, the young voters declined to choose.

Many young people in the bar had decided to cast a vote blanc, a blank ballot. The other half begrudgingly said they would vote for Macron.

The sense of disenchantment seemed to teeter between animated frustration and blasé resignation.

In the first round of voting, St Pierre and Miquelon strongly supported Mélenchon, with 35.45% of the vote.

St-Pierre and Miquelon

But in St Pierre and Miquelon, Le Pen and Macron were neck-and-neck for second and third place, receiving 18.16% and 17.97%, respectively. In an island community with just under 5,000 eligible voters, the difference between 18.16% and 17.97% was a mere five votes.

Alex Bry and Pierre Fouchard are cousins and best friends, but they are on the opposite ends of the political spectrum.

They are both 19, and first-time voters. Fouchard was the only one of his friends who said he would vote Le Pen, a decision he made because of what he sees as a kind of unfairness that permeates French society.

Bry argues frequently with Fouchard about politics, but they never allow it to reach the point of animosity.

Bry saw Macron as France's last chance to maintain its commitment to the environment and human rights. But in spite of his strong progressive bent he had a hard time deciding whether or not he would actually vote for Macron. For him, the vote blanc remained an option until the last minute. He said he voted for Macron "unwillingly".

Fouchard, on the other hand, voted for Le Pen despite expecting her to lose.

Around 1:00am, as bar staff made their way around the tables to prepare to close, Bry and Fouchard ordered a final round of cocktails. They decided to finish the night with a boisterous rendition of a Newfoundland drinking song - two smartly dressed boys who speak European French singing in English about fighting Quebeckers for the territorial integrity of Labrador.

A woman nearby leaned over and whispered: "A lot of people here feel Canadian on the inside, even just a little."

St Pierre and Miquelon voters casting their ballots in the second round of the 2017 French election

The polls opened on Saturday at the St Pierre town hall at 8:00 am.

A rooster in the garden of one of the neighbouring houses crowed at precisely the moment town hall officials unlocked the doors.

It was a polite and pleasant atmosphere, with none of the bitter disillusionment seen in the bar on Thursday night. The first person to vote in St Pierre was an elderly gentleman named Gérard Dagort.

In the end, Macron's victory was decisive, but voter turnout was the lowest in nearly 50 years and votes blancs were at a record high.

When St Pierre's own numbers were released, they closely mirrored the overall French result, with 63.88% for Macron to 36.12% for Le Pen.

It seems, then, that Marine Le Pen may have misjudged the impact of St Pierre and Miquelon's distance from France in her visit last year.

Sure, there are hockey jerseys and pickup trucks on the island and anything from France has to come on a cargo ship from Canada. But when it comes to politics at least, the people of St Pierre and Miquelon are as close to France as ever.

- Published8 May 2017

- Published8 May 2017