Irish immigrant’s arrest highlights race's role in deportation

- Published

John Cunningham had been living in the US without papers since 1999

After a high-profile deportation, undocumented Irish immigrants are on edge, and trying to help Latino immigrants who are more likely targets for immigration officials.

John Cunningham came to Boston in 1999. Like many Irish immigrants to the US, he arrived on a 90-day visa for summer work. But then he settled in, worked as an electrician and ran his own company, remaining in the country without authorisation.

"All of a sudden you turn around, so much time has gone by, and you start to realise what is going to be in store for yourself for the future," Cunningham said in a March interview with the Irish Times, external.

On 16 June, nearly two decades later, US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) agents came to his home to arrest him. He was deported to Ireland on 5 July. Because he arrived in the US under the visa waiver programme, one commonly used by European immigrants, he had waived his right to a hearing.

Ronnie Millar, who runs Boston's Irish International Immigrant Center, external, thinks Cunningham's decision to share his experiences and speak out for the rights of unauthorised immigrants in the United States made him a target for deportation.

A warrant was issued for Cunningham's arrest in 2014 after he failed to appear in court on an allegation he did not complete work he charged a client for.

But ICE would only confirm that his arrest and deportation was due to his visa overstay.

Cunningham became the first high-profile Irish immigrant deported under President Donald Trump, and it's created a chilling effect in Boston.

"There were shock waves sent through the community, a disbelief that this was actually happening," said Millar, a close friend of Cunningham's.

New citizens sing the US national anthem in Boston

It is a chill felt by people like Jerry. He asked to be identified by only his first name because he remains unauthorised to live in the US and fears deportation. When Jerry first arrived in the US on a three-month visa waiver in the summer of 2011, he hadn't made up his mind about returning to Ireland. "The lifestyle, the work, everything was just better here at the time. So things just kind of happened," he said. "I had a return ticket booked. I just never got on the plane."

The Migration Policy Institute estimates there are 16,000 undocumented Irish living in the US. The Irish Embassy in Washington puts that number closer to 50,000. Most live in Boston, New York or Chicago.

Like Jerry, many are hiding in plain sight, navigating a difficult world of privilege and panic as white, undocumented immigrants.

"I don't think anyone is outright targeting people who look like me," Jerry said, "But there's still a fear. You could be walking in the street and bump into the wrong person, you can get pulled over while driving, walk into the wrong building or show the wrong ID."

"Most people think undocumented and they think people who come across the southern border," Cunningham said in an interview with this reporter a year before his arrest. "They're not thinking about the Irish guy who lives right next to them."

Jerry, Millar and Cunningham all acknowledged that, as white men, they can fly under the radar of those who associate unauthorised immigrants with Mexico and Central America.

Where do America's undocumented immigrants live?

Cunningham recalled local police and immigration officials not questioning his status during stops. He felt that he was given a pass because of his Irish accent. He wondered if the officers would have treated him differently if he were black or brown.

As a whole, white and other non-Latino immigrants are targeted for arrest and detention at disproportionately lower rates, says Randy Capps of the Migration Policy Institute.

"It's the Latino immigrants from Mexico and Central America that are overrepresented in terms of arrests and deportations," said Capps.

Accusations of unequal treatment and racial profiling among immigrant communities have also sparked criticism in Boston about local media attention to Cunningham's arrest. Carol Rose, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts, said that for every one story of a white immigrant who faces deportation, there are many other stories of non-white immigrant experiences not told.

Rose points to Boston's Francisco Rodríguez, a Salvadoran immigrant who, after two denied asylum requests, had been granted a stay of removal every year since 2011.

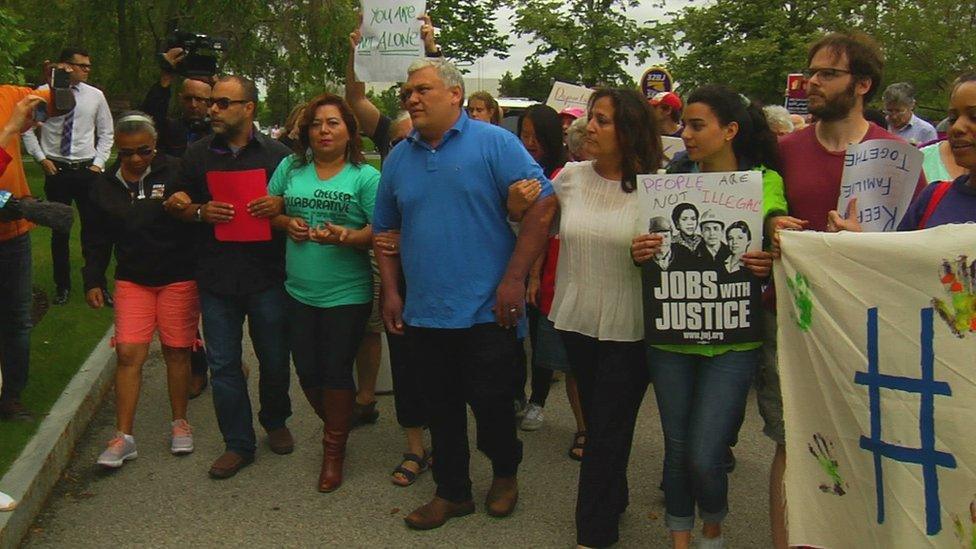

That changed this year under President Donald Trump, who greatly broadened which immigrants the government considers a priority for deportation. Rodriguez was arrested when he arrived for a check-in with immigration authorities in June and remains in custody while fighting his deportation to El Salvador.

Critics also point to racial bias in how Cunningham's story was told. Julio Varela, co-host for Futuro Media's In the Thick podcast and a Boston native, has often challenged what he calls an "Irish immigrant privilege" in local media. In a column on the Latino Rebels blog, external he argues Irish and other white immigrants like Cunningham are more often portrayed as model community members undeserving of deportation.

Francisco Rodríguez and supporters

It's why the Irish International Immigrant Center offers its legal and social services to more than Irish immigrants. Christina Freeman, a lawyer at the centre, said their "know your rights" workshops often include talk about racial bias and law enforcement. The participants "know there is a racial bias, they've experienced it".

"You look around the room and see who's in there and there's not one white face in the crowd," Freeman said. "It's because the teenagers being stopped the most often are teenagers of colour."

While white undocumented immigrants may benefit from blending in, there is still an impact.

Millar recalls his centre aiding an Irish woman so embarrassed to reveal her immigration status to her American-born family that when a parent died back in Ireland, she instead stayed in a hotel in the US to give her family the illusion she went home, rather than admit that she's undocumented and risk not gaining re-entry into the US.

Following Trump's electoral victory, Millar said there was an increased fear that Boston's previously welcoming stance toward Irish immigrants would soon change. Those fears were compounded following Cunningham's arrest, he adds.

"We are not in a good place as a society," Millar said. "As a nation, we've really lost our way, who we are and our values - being a country that's made up of immigrants."

The World is a co-production of the BBC World Service, PRI and WGBH. You can listen to more here, external.