Where Trump is seen as saviour

- Published

"What do I live off? I draw my cheque from the government every month": in Jamestown, almost 40% of the locals live on benefits

Jamestown, Tennessee, is one of the poorest towns with a majority-white population in the US. The area overwhelmingly voted for Donald Trump and locals believe new jobs will now come - but will that be enough to turn around decades of economic distress?

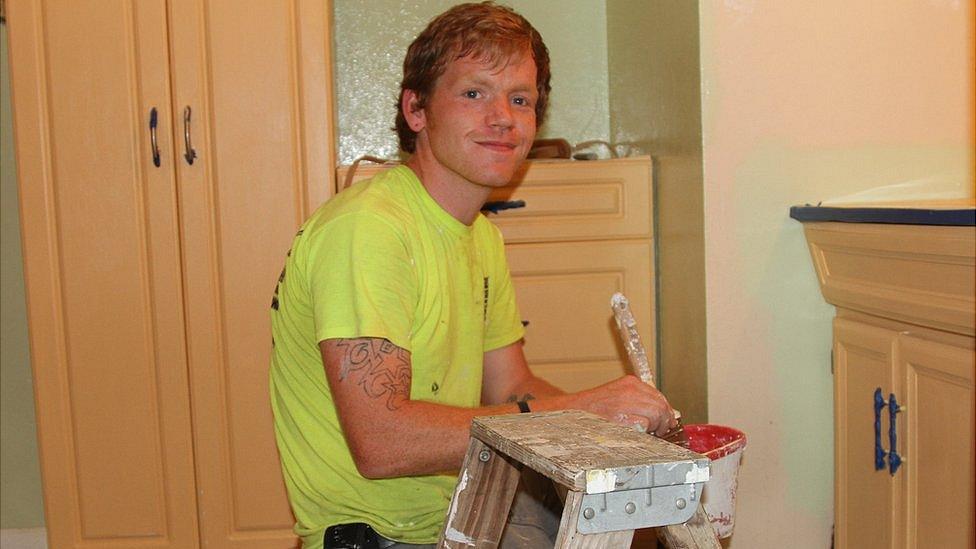

Nine years after his plumbing company collapsed at the height of the credit crunch, Clint Barta is feeling confident enough to start again.

"It's only been days, so it's a bit slow," says Barta who has been in the business for 33 years. "But I'm meeting with a builder tomorrow."

The plumber had to lay off 75 employees back in 2008 and commuted daily for an out-of-town job to keep his family afloat.

"For years, we saw nothing in this town," he says. "But now we live in 'Trump times' and it's all starting to change".

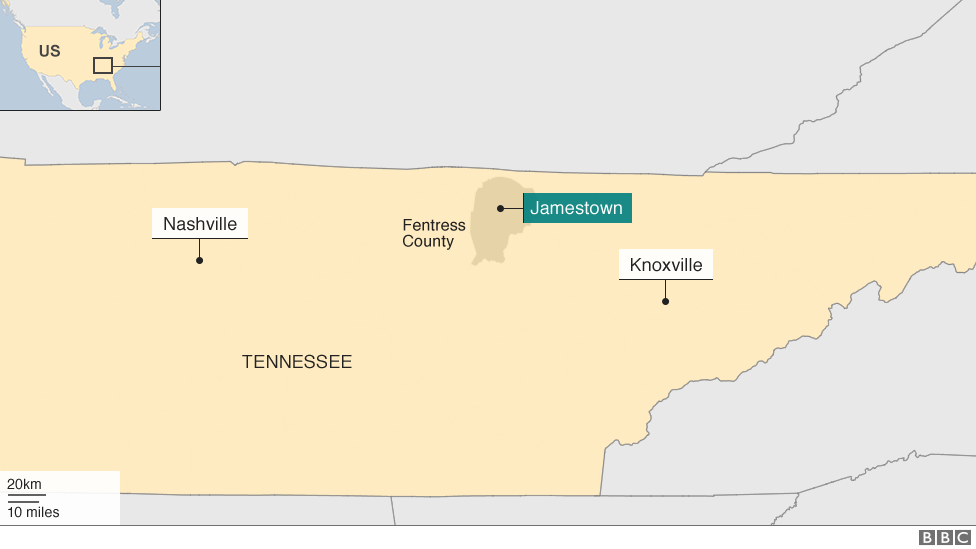

Barta lives in Jamestown, a tiny town of 1,900 people nestled in the fertile hills of north Tennessee. An area "with 230 churches and just one pub", as some locals describe it.

It's a two-hour drive from here to the nearest city, and the busy streets and shining high-rises of the state capital Nashville feel like a world away.

In Jamestown, the streets that make up the town centre are deserted.

Most of the family-run corner shops were forced to close down

A short walk takes you past row upon row of empty shops with bare shelves, broken blinds, and months' worth of post piling up under the doors.

There are dusty shop fronts, a florist with plastic funeral wreaths in the window, a thrift store, a few sun-bleached 'For Sale' signs.

Between 2008 and 2012 official statistics show Jamestown had the sixth lowest median household income of any town in the US. And by 2015 over half of its population was living below the poverty line.

But since Donald Trump won the election in November 2016, there's a new sense of optimism in the air.

"I am hopeful about his promise of bringing jobs back, I have already experienced it myself with my business reopening", says Clint Barta. "Trump is a businessman and I'd rather have a businessman in office than a politician."

Many echo his optimism. Voters in Jamestown and the surrounding Fentress County came out overwhelmingly in favour of the Republican candidate, who won 82.5% of the local vote.

"[We are] Republicans through and through, there's no denying it," Barta laughs.

Barta believes change is about to happen in this impoverished economy

White America

With a population that is more than 95% white, Jamestown is a textbook example of a small white working-class American town.

Fifty years ago it was a thriving hub with hundreds employed in local mines and three garment factories.

But then the mines closed and the factories left. Many here blame the North American Free Trade Agreement, Nafta, signed in the 1990s, for "taking our jobs south to Mexico".

Plans to turn Jamestown into a hub for the service industry failed to materialise, and neither did a new interstate highway that would increase commercial traffic.

The local industrial park today stands half empty. A giant Walmart did finally provide some new jobs, but also forced many "mom-and-pop" stores out of business.

Workers here drive for hours to out-of-state jobs

Unemployment in the area rose above 6%, much higher than the national 4.3%, and on a par with Alaska and New Mexico, the two states with the worst rates in US.

But despite all this, the latest state-level statistics are starting to show some good news - and giving people hope.

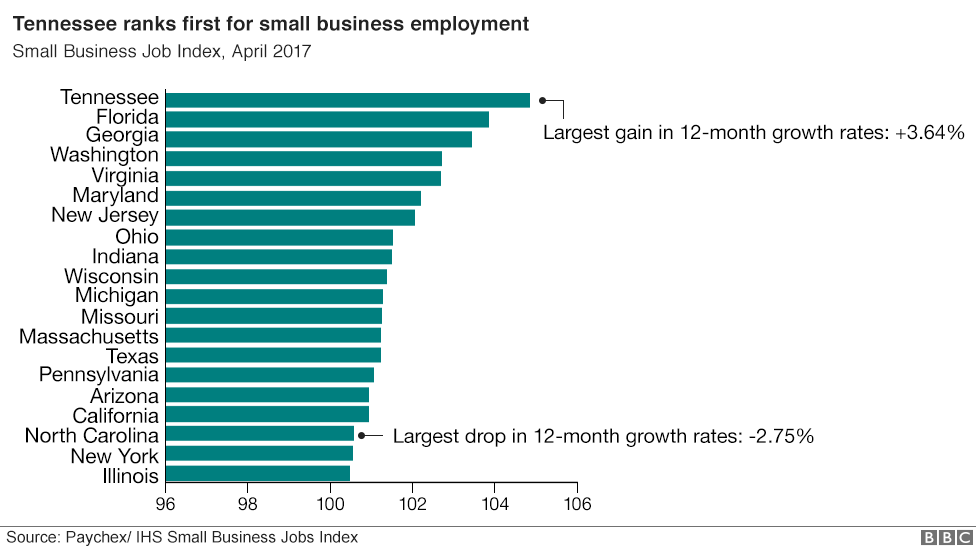

During the first 100 days of Donald Trump's presidency, Tennessee became the country's number one state for small business job growth, according to the Paycheck/IHS index.

And in May the state saw its largest month-to-month unemployment drop in more than 30 years, figures from the Bureau of Labour Statistics show.

For people here, it's confirmation that their new president is delivering on his campaign promise to generate 25 million jobs and become, in his own words, "the greatest jobs producer that God ever created".

In fact, the trend actually started before the change of administration, thanks to relatively low tax rates and the low cost of living in the state.

But J. Michael Cross, the county executive of Fentress County, is definitely feeling optimistic.

Putting their hopes in the Trump administration

"Thirty-five percent of all large cranes in the US are said to be in Nashville right now", he says. "New buildings of all sorts are popping up."

Although that figure is hard to verify, Tennessee's multi-million pound construction blitz has been well documented.

And Mayor Cross - whose patch includes Jamestown - is a firm believer in "trickle-down economics".

"It may take a year or three, but at some point in time we will benefit from some of those new jobs and industries," he says.

Hover over the curve to see figures for each month.

"I ask friends when I go hungry"

At the Jamestown food bank, those waiting to receive their free box of provisions know little about state statistics.

As they file through this blue, galvanised steel shed they probably have other numbers on their minds - working out how to make each precious food parcel last.

Fentress County's weekly food bank is a lifeline for many families

Demand is so high that families are only allowed to come here once every six weeks.

"Resources won't stretch any further," says Sally Frogge, a sprightly 77-year-old volunteer, who is updating the records on a computer.

Like most of the 15 volunteers here, she is from one of Jamestown's many local churches.

It is a precise, choreographed operation.

The volunteers walk between pallets and crammed shelves, filling boxes with basic supplies - packets of rice, tinned fruit and vegetables, biscuits and flour. The Methodist church donates washing powder and sometimes there is also soap and toiletries to hand out.

The food pantry is run by volunteers from local churches

The food bank helps out 150 families every week. A rough estimate says that one in every six homes in Fentress, a county of 17,000 inhabitants, depends in some way on food banks to feed themselves.

"There are so many people on disability income, the elderly, the unemployed…", says Sally. "[People] tell us they are looking for work and that goes on and on for months".

Frogge works at the food pantry

Kenny Jones, 51, is one of the hopefuls.

"I haven't been here for a while," he says. "I don't want to make it a habit. But work is non-existent, whenever a position comes up there are 20 people in line waiting to take it".

Jones' story is typical. He worked all his life in the construction industry, driving from state to state, picking up short-term contract work.

It was a hard, hand to mouth existence, living out of a suitcase. When his wife and children left him, he decided he couldn't do it anymore.

He couldn't afford to keep his car, and in a town where public transport is almost non-existent he has to rely on friends to give him lifts.

"I didn't want to live out of a suitcase any more", says Kenny Jones

Kenny says he can make the food bank provisions last 20 days if he eats once a day. But that still leaves another 22 days before he can come back for another box.

"I have friends that I ask for help when I go hungry," he says.

He's heard there might be a factory opening up soon and he's hoping to find out what work might be on offer. But he's not holding out much hope.

"This town will eat you if you let it," he says as he loads his food box into a friend's car. "And it'll never get better."

A job centre... with no job offers

"The employment office? I don't think it exists any more," says the local librarian. It's scorching in the midday sun and the library is the only open door in Jamestown's complex of municipal buildings, organised around a car park.

She's wrong. But the office is so small and tucked away that it would be easy to miss.

Sitting at a single desk in a windowless room at the end of corridor, manager Janice Campbell is happy to chat.

She points out the computer for doing job searches which is almost always free.

Many of the jobs nearby are essentially seasonal, so workers can only secure an income for part of the year

On the jobs board, there are just three postings: one for teaching jobs in local schools, another one for a position with a charity for the disabled.

The third one is for the role of county Sheriff, after the previous incumbent stepped down and pleaded guilty to coercing vulnerable female prisoners into sex.

With few jobs on offer, Janice gets few visitors. But recently she's had a flurry of calls from people who, like Kenny Jones, have heard a factory is about to open up.

"No-one's said anything to me", says Janice. "But the rumour's out there because 10 or so people are contacting us daily asking the same thing."

J Michael Cross, the County Mayor, in his office in Jamestown

Back in the Fentress County council offices, Mayor Cross is crunching the numbers.

The official stats for the current state of affairs in Jamestown make pretty grim reading.

The town's average household income is just $15,700 (£12,082), compared to a country-wide average of $53,000. And a shocking 50.5% of the local population lives below the poverty line, compared to a national average of less than 15%.

People have got used to things being bad, says Mayor Cross. "The biggest challenge is the negative mentality of many residents."

The mayor is adamant things are looking up, with several local businesses taking on staff recently.

"Three or four other businesses have added 75 to 100 jobs to the local economy," he says, a significant amount for an economically active population of about 10,000.

But there will only be a real turnaround if Fentress County can attract new businesses from outside the area. And he believes President Trump can help this to happen.

"I've always researched business models and I have studied Trump for 30 years, before even dreaming he would get into politics," he says. "The poor, rural people look at him as a refreshing break from old school politicians."

"There is confidence and people will be more willing to take risks".

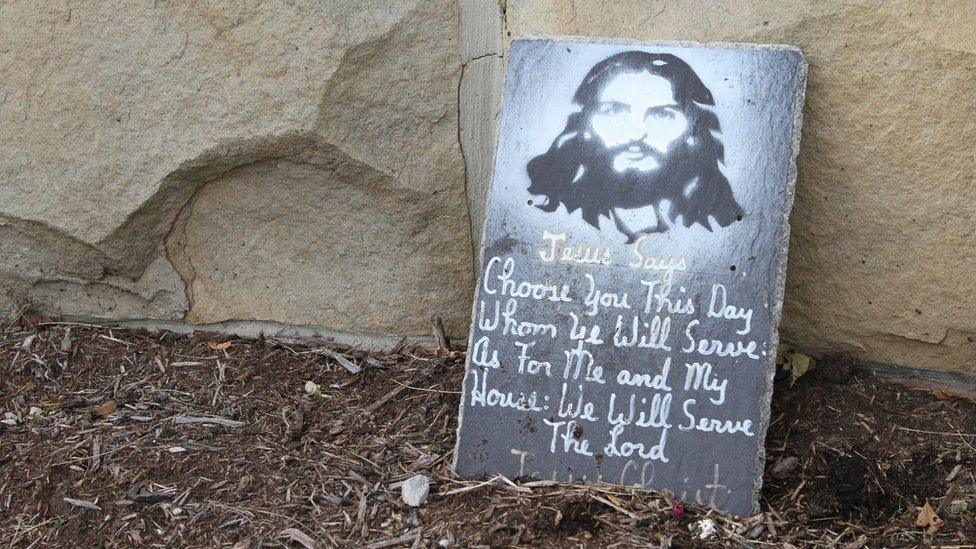

The county is the "buckle" of the Bible Belt

Even the churches are in expansion mode, he says, which may give the construction industry an extra boost.

And that's no small opportunity: Fentress County is at the heart of America's Bible Belt. On the road into Jamestown alone there are more than 70 churches, with their crosses and billboards lit up with bible quotes.

"Are there 230 churches in the county? Could be", says Cross, who doesn't know the exact figure but thinks that doesn't sound off.

And the new factory that so many people are talking about?

"We are in conversations," he says. "A big company from outside state, could mean up to 150 jobs. That's all I can say, let's hope we can bring good news in a couple of months."

"I could hire a lot more people, if I could find people who really want to work", says Dillard

Sweating in his dirty work overalls, Timothy Dillard is sawing three-metre wooden planks into skirting boards.

After 22 years in the military and four more as a missionary in Africa, he returned home to Jamestown 18 months ago and set up a construction company.

"Service with a higher purpose," says the motto printed on his business card, followed by a biblical reference. Micah 6:8: "What does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy".

Dillard has a staff of five - all local young people, one of them recruited just yesterday. And today they're renovating a run-down cottage outside town.

"With the crisis a few years ago, everything came to a halt," he says as he reaches out for the next plank. "But recently, the hiring has gone up and people are more willing to spend."

Many of his clients are retired people who have moved to Fentress County attracted by low property taxes and cost of living.

Many come for the horse riding. With its tracks and hillsides, this is a dream destination for the equestrian community. "Some stay," he says. "That all creates jobs."

"It's been really hard here," says Sam Duval, self-taught painter: "Typical small town, your name matters"

Small companies like Dillard's, employing several to a few hundred workers, make up 94% of business in the US. And everyone here understands that President Trump's promised new jobs will only come in large numbers if those small firms are able to expand.

But in a place that's been in such a long downward spiral, turning things round is not easy.

"The biggest challenge is finding people who want to work," says Dillard. "People come for a week and as soon as they get paid they don't show up again. Why work, when you've got free money?"

In Jamestown 39.6% of all adults of workforce age, from 18 to 65, are living off welfare payments - compared to a national average of below 15%.

And to many small-scale employers, that seems like a big disincentive for people to get into the workforce.

"Generation after generation of people drawing checks", he says, taking a break from his work bench.

"How do we fix that? I don't know the answer… but then, I don't make policy."

Trailers, dogs and drugs

Some of the people Tim Dillard probably has in mind are to be found in Jamestown's Sunshine Lane.

Its name belies the grim reality of a pockmarked old concrete street lined up with crumbling trailers and wooden shacks, abandoned cars, stray dogs and piles of rubbish that occasionally get set alight, releasing a thick smoke.

The doors - those that exist- are mostly left open, windows covered with fabric and cardboard in the place of glass. Some houses have porches made of sheets held together with rubble and old armchairs outside.

"What are you looking for?" asks Connor, strong, angular faced and sun-tanned, his neck covered in scars from past injuries.

It's the middle of the working week but everyone here seems to be home - although most prefer to hide away at the sight of strangers. Dogs bark unwelcomingly.

Connor, who's about 40, lives at the bottom of Sunshine Lane, in a little cabin with peeling paint. He has one room which he shares with a woman who hides behind the fabric hanging in the doorway the moment she sees us. He can't walk much: he has a broken back, he says, after an injury he had while working at a local garage, fixing trucks.

"What do I live off? Well, I'm on disability (allowance), I draw my check for some 600 dollars," he replies.

"I don't know if there are jobs now because I don't go to town often, but to those that say that people here don't want to work, let me tell you: the jobs are bad, they always have been. There are so many like me, who get hurt because the job is dangerous and then you are on our own, in pain and with no other jobs to go for."

Pauline (on the left) lives alone in Sunshine Lane

His neighbour opposite, with whom he doesn't really get along, has a similar story.

Pauline was diagnosed with lung cancer, had surgery twice and lost everything: her job at a bar and the few savings she had. Painfully thin, emaciated "with the cancer back" and on sickness benefit, she lives alone in Sunshine Lane. She lost contact with her family but a friend visits from time to time.

"Now I'm here, no choice, no joy", she says, lying on a shabby sofa outside her home.

Pauline has just two broken teeth, a half-smoked cigarette in her right hand and another, not yet lit, in her left. Her face is pocked with countless red blemishes and has track marks of syringes on her arms.

Sunshine Lane is also the place where Jamestown's biggest tragedy is played out in plain sight.

Drugs. Some heroin, but for the most part methamphetamine and prescription pills, according to Sergeant Brandon Cooper, a spokesman for the Sheriff's office.

Sunshine Lane, everyone agrees, is a safe haven for consumers and dealers alike. Connor says he takes pills "every so often" to ease his back pain, although he doesn't see himself as an addict.

As in many other American towns, drug addiction is at epidemic levels, although the county does not provide any official figures.

But they do provide crime statistics which give an indication of the extent of the problem.

Fentress County has a brand new prison, built in 2014 and nicknamed "the Taj Mahal" by locals, with space for 166 inmates.

The jail is currently at full capacity and 80% of the inmates are in for drug-associated offences.

Illegal prescription pills are an "ongoing problem" says Detective Brandon Cooper

Drug abuse is a very real obstacle to any official plan to tackle unemployment.

"It is hard: how can drug users be productive? I question whether those people want a job hard enough to overcome their drug addiction," asks Mayor Cross.

For Mark Clapp, senior emergency doctor at the hospital, the issue's more complex than that.

"My experience tells me that it takes them to have something radical or catastrophic in their life that triggers the desire to change," he says.

He estimates that 10% of the population suffers from addiction and here he sees "two or three serious drug-related admissions" every time he's on shift in the emergency room.

"I just got tired of signing deaths certificates," says Clapp

Clapp was an obstetrician for 20 years until he "got tired of signing death certificates" for the parents of children he had helped deliver, due to overdoses. He moved to the emergency room instead but, inspired by his religious beliefs, he also runs a rehabilitation clinic for addicts.

"The nature of the jobs we have around here plays a part: young people do physically demanding work, they wear out their back, get prescriptions to manage pain - and they never get off them. As a doctor, what do you do with a 22-year-old with chronic pain who is already on a high dose of narcotics?"

The solution, he says, is not just more jobs - but better ones.

"There is no way out if we don't stop the brain drain of the brighter kids, who go away for college and never come back."

'Trump is going to do great things'

Nancy Lee Thompson is having breakfast as she does at least twice a week in the West End cafe.

It's a typical American diner and at 8am it's buzzing with customers and smelling of fry-ups and coffee.

Nancy is 68 and moved here from Florida, one of a growing number of retired people living in Fentress - a new demographic that now makes up 28% of the local population.

She's also a proud Trump supporter.

"I love Trump," she says. "He is going to shake things up that needed to be shaken for a long time, he is not part of the political system that has dragged us down."

"There are so many people here that have never known the satisfaction of a good day's work. And that's a shame, because it is a good feeling. But that's about to change".

Despite widespread optimism, some businesses depend more on the weather than on the social and political mood

"We have seen our business improving recently, that's a fact," agrees Bob Washburn, one of the owners of Wolf River Valley, a nursery that trades decorative plants and some vegetables.

He hasn't got a figure to hand, just a perception that comes from years of attending to his customers day in, day out. His business - peonies and pumpkins, geraniums and chillies, chrysanthemums and tomatoes - depends more on the weather than on the mood in Washington DC, he admits, but it's also affected by people's outlook.

"People seem more optimistic and optimism changes the economy. As a business person, I am always looking for lower taxes and looser regulations, which he has promised," says Washburn.

"We feel we have reached the bottom and the only way is up. And country people here are very proud and they feel that for the very first time they had an input into deciding who the president is. The unspoken, silent great majority," adds Washburn.

Deborah York runs a local state park and museum and says tourism is growing

At the (only) local bar

But not everyone shares the enthusiasm.

T'z Pub is Jamestown's only bar. It's housed in a shed down a gravel track and, like the West End cafe, it has a loyal clientele.

A dozen patrons sit around the horseshoe-shaped bar, all part of a single conversation. On the other side of the bar is Theresa Hale, handing them cold beer bottles and getting her tips through Bella, a dog who catches the patrons' one-dollar bills with her mouth and diligently brings them to her owner.

Hale is a Texan who you wouldn't want to get on the wrong side of. She came to the town "following a lover, but it didn't work out" and decided to take over the once notoriously rough pub and clean up its reputation. She banned guns and fist fights and saw off undesirable regulars who used to leave the car park full of syringes.

Back then the place was always full, but she prefers it like this, with the pool tables empty and a few loyal customers.

"Fentress: the county with 230 churches and only one bar," she laughs. "We should print t-shirts with that slogan!"

Conservative values and religious beliefs played a key part in giving Trump an overwhelming electoral victory in this region

This is a "dry county" with strict legislation against alcohol sales. In the last election there was a move to ease the restrictions but it was voted down.

"Trump? What do you want us to say about Trump?" says one of the customers, his tone distinctly unfriendly. There's suddenly an uncomfortable silence.

"I can tell you why nobody wants to talk: because nobody wants to be associated with the bar," says Teresa. "We're in the Bible Belt and that says it all. The church dictates the way of life and the politics of this place."

But the conversation soon starts up again.

"Here people feel that they share values with the president, and even more so with the vice-president Mike Pence" says one man.

"And then there's this idea that by making America great again, whatever that means, we will all individually benefit in this part of the state. That's nonsense," says his companion, a twenty-something woman, by far the youngest in the group.

"Nothing will change just because there is change at a federal level. We will still be run by the same handful of rich, powerful families of the town."

Big chains came in and brought some jobs - but some complain they are changing the face of the town

New shops have opened in Jamestown's main square

Trickle-down effect

Outside the courthouse in the centre of Jamestown, a team of gardeners are planting flowers.

"We try to do things that are uplifting. Psychologically, get people to think that good things are happening," Mayor Cross explains.

In the square across from his office a new gym and boutique have just come into business - their "Now Open" banners livening up the row of empty shops.

On the next block, Clint Barta, the plumber, is washing the windows in his wife's boutique - one of the few to have remained opened on the main street.

He says he's taking heart from the boom in Nashville and keeping his fingers crossed that it will have a trickle-down effect.

To give himself a boost, Clint has started going to the First Baptist church, partly to fulfil his desire "to spend some time with the Lord," he says, and partly because it is "good for the networking".

"The more you get known, the better opportunities you have."

"I truly believe that Trump will do everything he has promised us," he says. "I've seen a lot of good things from him."

"Yes, we all make mistakes, we live and we learn. But with him, I'm not disappointed one bit."

Text and photos: Valeria Perasso. Video: Hetal Gandhi.