Affirmative action: Do white American students really get a bad deal?

- Published

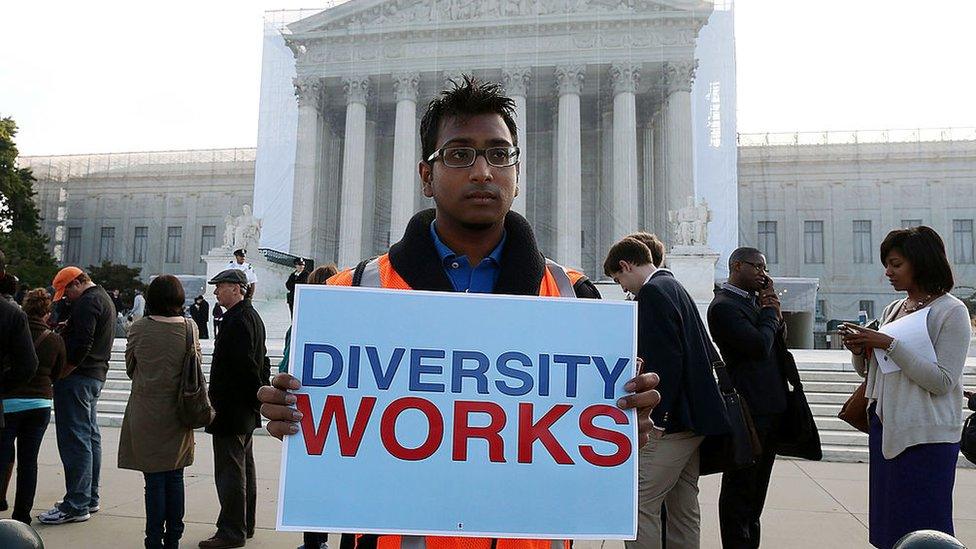

A protester in favour of affirmative action stands outside the US Supreme Court in 2012

Affirmative action - a touchstone of the US culture wars - is back in the headlines after a claim the justice department was considering a plan to sue campuses with race-conscious admissions programmes.

The federal agency denied reports that it might file lawsuits against any colleges and universities perceived to discriminate against white applicants.

The justice department said it was actually trying to resolve a complaint - left unresolved by the Obama administration - alleging bias against Asian-Americans in higher education admissions.

The story reopened the debate over allegations that a policy designed to increase diversity in academia has been unfair to certain students.

A US Supreme Court ruling in 2016 gave universities latitude in considering race as one of the many factors in a "holistic" evaluation of an applicant, but rejected the notion of fulfilling a racial quota.

Do white American students really lose out to minority students? Here are two opposing views, from former justice department official Roger Clegg and civil rights lawyer Brenda Shum.

Is affirmative action fair?

Mr Clegg: I simply think it's unfair to treat people differently because of skin colour and as a lawyer, I think that it's not consistent with the way our laws read. I think it's a bad idea and I would oppose it if I were somehow or other a beneficiary of it.

I remember when I was interviewing for a law professor job at one point, and I was told point blank that I was not likely to get this job because of my skin colour. I was taken aback that I would be told that so bluntly by someone in a law school.

Here is somebody who has worked very hard and yet they are being told that their odds are going to be not just a little less, but a lot worse than other people who have lower academic qualifications but the right skin colour.

The personal stories are certainly out there, but I think for anybody who thinks seriously about this question, giving a preference because of race ought to raise red flags.

Ms Shum: During law school I had a male classmate talk to me about how he believed that I that was admitted to the law school simply because of affirmative action. This really wasn't a hostile conversation, I think, it was an attempt to open up a dialogue and this is truly what he believed - that there was a number of white applicants, particularly white male applicants, who were qualified and denied admission to our law school [University of Washington School of Law in Seattle] simply because the school had a commitment to diversity on campus.

The school had a diversity policy that, consistent with the constitution, really looked at all aspects of their prospective student population. I think I was one of the first classes that had slightly more women than male law students. They made a really concerted effort to have racial diversity and I think that was really instrumental to adding to the discourse that we had during our law school career.

Both personally and professionally, I've had the benefit of seeing how instrumental race-based admissions policies can be in terms of ensuring that there are integrated learning environments that really promote those educational benefits of diversity - that research is telling us - to all students.

In the wake of a US Supreme Court decision over Michigan's affirmative action policies, the BBC takes a look at American public opinion on the issue.

Are white students discriminated against?

Mr Clegg: I think that in a country that is increasingly multi-ethnic and multi-racial that kind of policy is simply untenable. I think the only legal approach that can possibly work is one that treats everybody the same regardless of their skin colour or what country their ancestors are from.

Nobody disputes that racial discrimination is occurring but the dispute is about whether the discrimination can be justified or not.

We're talking about significant disparities in test scores and grades. Not surprisingly, that means that you also see disparities in how the students perform once they're admitted. If you admit a student that has significantly fewer academic qualifications than most of the student body, that student is more likely to struggle and less likely to graduate, less likely to make good grades or less likely to get into that major or discipline they intended to major in.

Ms Shum: I think it's a myth that race-based admissions benefit only students of colour. One of the other things I've encountered professionally is this perpetuation of another myth, which is that qualified, white applicants are being displaced from college programmes by under-qualified and under-prepared minority students. I think that this is a really divisive way of looking at these issues and really undermines a university's commitment to ensuring that our college campuses reflect the world that our students are living in. Quite frankly, I think it's offensive to students of colour to imply that the only reason they were extended an offer of admission is because of affirmative action.

Is it time for affirmative action to go?

Mr Clegg: I understand the visceral sense that African Americans have been treated badly in this country for a very long time, and right after we got rid of Jim Crow [segregation laws], it wasn't such a bad idea to give special consideration over someone who was a recent beneficiary of Jim Crow. But now we're in 2017. Jim Crow is long gone and we're talking about giving Latinos a preference over Asian Americans. What possible sense does that make?

I think the right way forward is to stop treating Americans differently because of their skin colour and what country their ancestors come from. We should all do that in our personal lives and our laws should reflect that, too. It's not a tenable approach to categorise people for their race and ethnicity and expect anything good to come out of it.

What we're trying to do is to help people who are in poverty. I have no objection to that, but there are plenty of white people and Asians in poverty, too. Why are we discriminating against those people in favour of wealthy African Americans or wealthy Latinos? Don't use race as a proxy for somebody's socioeconomic status.

The history of discrimination against African Americans is certainly a reality, but again, that doesn't tell us the way forward.

Ms Shum: There is a lot of empirical data that demonstrates that the socioeconomic status of students alone does not achieve sufficient levels of racial diversity on campus. I think that this idea that simply merit-based decisions are sufficient is false and don't take into account not just the history of segregation and discrimination in K-12 and higher education in the US, but the current reality that students on our college campuses continue to grapple with some of the tensions directly related to race.

It is important to give our universities the ability to use race-based admissions as just one essential, but not the only way of getting at a campus climate that is going to facilitate meaningful discourse and dialogue.

Fostering education opportunity for all students is a national interest and we owe it to our students to provide them with integrated learning environments that are reflective of the world in which they're living, and really promote their ability to learn and develop the skills necessary to compete and be successful in a multi-cultural, global environment.

Who are the contributors?

Roger Clegg is president of the conservative Center for Equal Opportunity and a former top official in the justice department's civil rights division under President Ronald Reagan and George HW Bush.

Brenda Shum is director of the Educational Opportunities Project at the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. She oversees litigation designed to guarantee that all students receive a quality education in public schools and institutions of higher learning, and to eliminate discriminatory practises in school discipline, school funding and special education.

What is affirmative action in US colleges?

Affirmative action, or the idea that disadvantaged groups should receive preferential treatment, first appeared in President John F Kennedy's 1961 executive order on federal contractor hiring.

It took shape during the height of the civil rights movement, when President Lyndon Johnson signed a similar executive order in 1965 requiring government contractors to take steps to hire more minorities.

Colleges and universities began using those same guidelines in their admissions process, but affirmative action soon prompted intense debate in the decades following, with several cases appearing before the US Supreme Court.

The high court has outlawed using racial quotas, but has allowed colleges and universities to continue considering race in admitting students.

Critics rail against it as "reverse discrimination", but proponents contend it is necessary to ensure diversity in education and employment.