Houston floods: Uninsured and anxious, victims return home

- Published

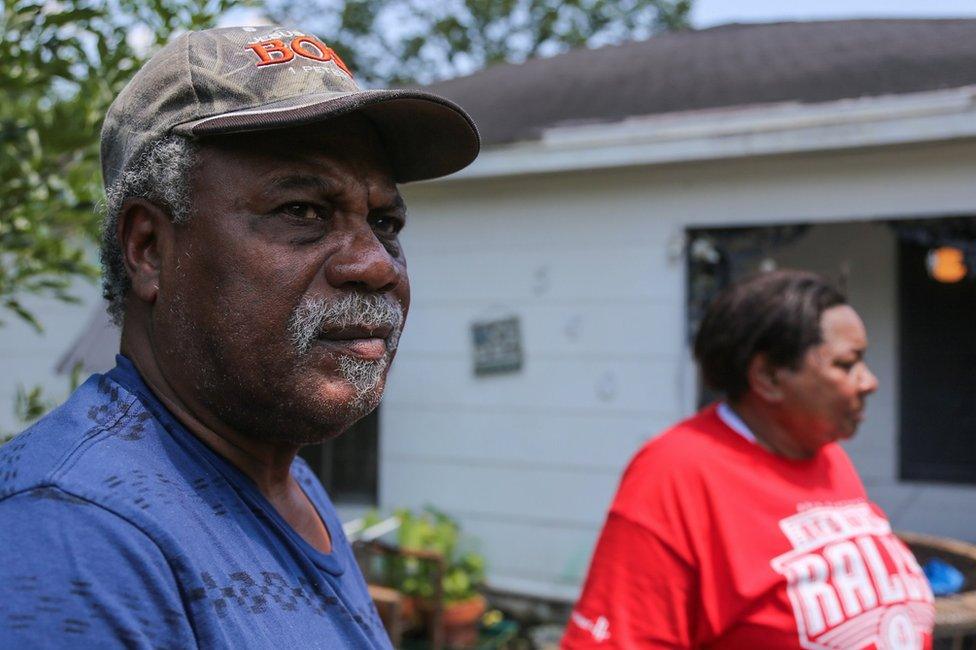

"I don't know where to start" - Herman Washington and his wife Mary Woodard found their home wrecked

As the water recedes in Houston, three families return home to survey the damage from Hurricane Harvey. Like so many others, they have no flood insurance and no way of paying for repairs.

At each house it was the same: a neat line, visible from the street, that showed where the flood finally abated. The lines ringed the small, one-storey homes in northeast Houston, where three bayous wind through the streets carrying water to the bay. For many of those returning home for the first time, the line would separate what was salvageable from what was lost.

At James and Rose Hert's house, a few hundred yards from the Greens Bayou, the line crossed the screen door about 5 ft from the ground. The water came in so fast it was up to Rose's neck by the time they waded onto the front lawn on Saturday, she said. At 59, recently recovered from thyroid cancer, and with arthritis that forces her to walk with a cane, Rose can't move fast. Neither can James, who's 63 and has nerve damage to his right leg and partial vision in his left eye.

The couple first made their way to a neighbour's house, on higher ground, but that too filled with water. Eventually they were pulled from the flood by a man with a truck, who drove them to a bus which took them to the mass shelter at the downtown convention centre. "I was terrified for my life," said Rose. "But that man was like an angel sent from heaven."

Their small, two-bedroom house, part-clapboard and part-brick, was a wedding anniversary present for Rose, purchased 23 years into the marriage and paid for with nearly all the money they had. Rose called it her castle. With the money left over she bought furniture - two couches, an armchair, a wooden dining table and a new refrigerator.

The most important piece of furniture though was an old one - an antique secretary desk handed down through three generations of women in Rose's family. She planned to pass it on to her daughter. She cried at the shelter when she thought about it. She couldn't face going back to the house, she said, so when James returned for the first time on Thursday he went without her.

When he turned the key in the lock, the door wouldn't budge. It would be the same at other houses, the first sign that the furniture inside had been picked up by the water and soaked and dumped back down where it didn't belong. He couldn't have known, as he forced the door, that it was Rose's secretary desk in the way, toppled onto its back, one leg already broken, but the glass, miraculously, intact.

As the door inched open, the rank odour of the water hit. It had seeped into the couches and the carpets and pooled between the floorboards. Underneath the water line, the walls were stained and Rose's prize furniture lay tumbled about. The fridge was on its side, blocking off the kitchen. None of it was salvageable.

Above the water line, the couple's marriage certificate hung unscathed in a frame, alongside James's army discharge and diploma, and a picture of Rose's late mother. "I guess that's something," James said.

Earlier, at the shelter, as he kissed Rose goodbye, his eyes had filled with tears. He was not given easily to emotion, she said. Maybe for a two-tour veteran of Vietnam, with 12 years service, the flood did not seem too tough. Later, at the back of the house, where the water line was 7 ft high and the deck was caked in mud, he paused for a cigarette and stood in silence looking down towards the bayou.

"There's $20,000, $30,000 worth of damage here," he said, looking back. "We just don't have it. We don't."

James Hert bought a house to mark his 25th wedding anniversary. Two years later, he will have to sell

Insurance experts estimate that only about 20% of those in Houston's worst hit areas have flood insurance. The Herts don't have any. The premiums were too high, they said. They live off $1,100 dollars a month in disability payments. After their other bills and outgoings, that leaves about $100 spare.

The number of homeowners across Houston with flood insurance dropped 9% over the past five years and as much as 23% in some counties. Harris County, where James and Rose live, has 25,000 fewer flood-insured properties than it did in 2012, according to an Associated Press review of government data.

Mary Woodard and her husband Herman couldn't afford the insurance either. The floodwater that washed through their house, a few miles south of the Herts in a low-income neighbourhood by the Hunter Bayou, was the latest in a long list of financial and personal hardships for the couple.

Herman, who's 63, had to retire from his work as a removals man last year after a stroke badly affected his right side. Mary, who's 59, worked 14 years in the local courthouse before retiring in 2011, after a diagnosis of osteoarthritis.

"It's the stink that gets you," Mary said as she pushed open the front door, entering her home for the first time after six nights in two different shelters. The tiled floor was slick with mud, the furniture soaked, the bases of the wooden cabinets warped. Food had floated out of the lower drawers and off the shelves and begun to rot on the floor. Mary didn't really care about what was beneath the water line, she wanted to know if the pictures of her first son and her first daughter had survived.

"I lost him when he was only eight years old," she said, fighting back tears. "That's when he got drowned in the pool. And my daughter, she got killed just about 12 years ago now. Her boyfriend killed her. That's why I was so glad to see those pictures. That was very important to me that they survived. Very important."

Much of Mary's income had been diverted to helping raise her daughter's four sons, as well as to taking care of her other three children. It didn't leave much for savings to help her and Herman through retirement. Like the Herts, they have about $100 spare each month.

"We don't have the insurance or anything," she said. "The few companies we did talk to, they were either too high or they didn't carry the flood insurance."

There was no money to pay for repairs, she said, they would have to move on. "We'll salvage what we can. I probably couldn't stay in this house anyhow, not after this."

"It's much worse than I thought," said Mary Woodard when she saw her house for the first time

The only hope for couples like the Woodards and the Herts is the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Fema will give money to uninsured homeowners to cover repairs and emergency costs. The grants are capped at a maximum of $33,300, but most will get significantly less.

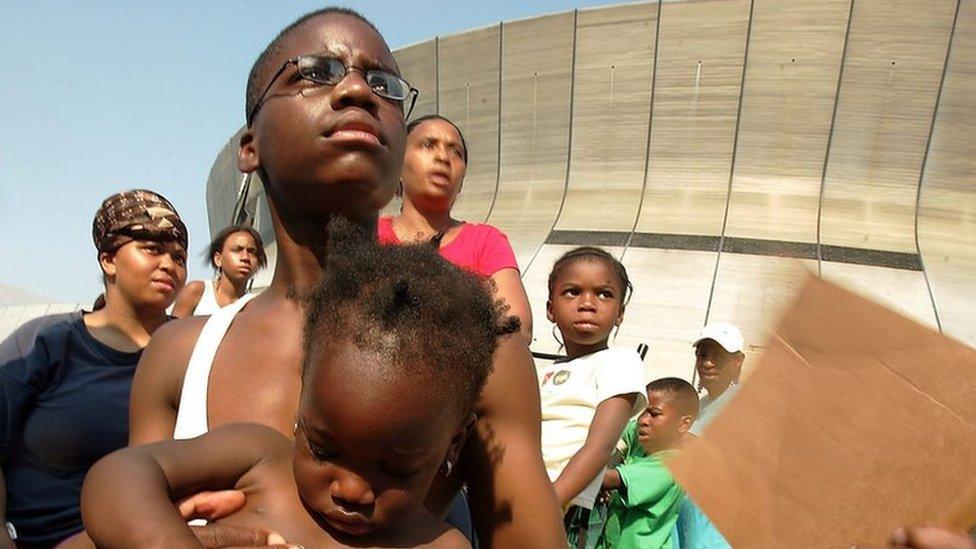

At the convention centre in Houston, a long line of people formed early every morning, waiting for hours to find out if they can claim. Mary and Herman had spoken to a Fema agent on Wednesday and he told them someone would be in touch within 10 days. By that point, they'd been in the shelter for five sleepless nights.

"I've had maybe eight hours sleep since I got there," said Mary. "You get an hour here, an hour there. There are people walking all around you and people fighting. It's a lot of chaos. It's 2am before it starts to get quiet."

The first call from Fema will tell Mary and Herman whether they are eligible. Then they will have to wait up to 30 days for an adjustor to visit the property and assess how much they can claim. In the meantime, they hope Fema will pay for a hotel room. Mary's eldest son and her elderly mother both live in Houston but they both flooded just the same as Mary. "Eventually we all winded up at the convention centre," she said.

Mary Woodard and her husband Herman found their grandson's toys floating across the road

James and Rose had been told they needed to go online to apply for relief. They had spent five days in borrowed clothes - James in an old sweatshirt and tracksuit bottoms, Rose in a pink nightgown - and they were overwhelmed. Three attempts to apply on a borrowed smartphone had failed as the Fema website repeatedly crashed.

Rose sat in the cavernous hallway of the convention centre and wept. She looked exhausted. She was still recovering from her brother's suicide last year, she said, and the loss of her mother two years before that. And now this. Two years after moving in, her dream home was gone.

"We put a tin roof on, we put new flowers in, we painted it," she said. "We fixed it up. It was my little castle, like no one else could describe it. It was all I ever wanted."

But it was cheap, too, partly because it needed fixing up, partly because it sits on low ground near the bayou, and that puts a significant premium on the flood insurance. Just over the road, where the ground is higher, flood insurance costs about $200 a year. On the Herts' side of the road, the premiums can run into the thousands of dollars.

Texas law stipulates that anyone in a Special Flood Hazard Area must have flood insurance, but only if you have a mortgage, people who own their homes are exempt. And the vast majority of those flooded by Hurricane Harvey fall outside the hazard zones and they never expected to see water washing through their homes.

"There's a lot of people here that have never been flooded," said Mark Hanna, from the Insurance Council for Texas. "And if you don't have to have flood insurance, and you've never been flooded before, a lot people say 'Hey, the water's have never been this high, we'll be OK'.

"People weren't prepared for a thousand-year flood. Who is?"

Rose Hert called her home her castle. She couldn't bear to see it after the flood

Frank and Melvin Lee Rogers never thought it would happen. The two brothers had been flooded once before, when Storm Alison came through in 2001, but it was nothing like this. They escaped on Saturday with just the clothes on their back and one of their cats, a tiny kitten called Squeaky.

Frank, 70, and Melvin Lee, 63, live in the Lakewood neighbourhood by the Halls Bayou, which cuts across the bottom of the street on its way to the Buffalo Bayou further south. The water had washed through the trees, leaving detritus in the branches as it went, including an old manual lawnmower which hung tangled 10 ft off the ground.

"I live down on the corner there, the white house with the blue trim," said Frank, as they crossed the bayou on foot on the way home. "You can see the dirt on the side of the house. That's the water line right there."

At the front door, the smell was so strong it seeped out of the building. Inside, a floating couch had punched a hole in the wall and smashed through a glass coffee table. Scores of worms and a small snake lay dead on the carpet. A wall calendar, neatly marked off for each day before Saturday, was cut in half by the water line, the last two weeks of the month underwater.

Frank Rogers stands in his kitchen on his first visit home, with the waterline visible behind him

Frank, a Vietnam veteran who settled in Houston and became a plastics mould operator, called out for Goldy, their five-year-old cat, who they couldn't find when the water began coming in through the walls. "No Goldy," he said. "She's gone, or dead."

Outside, his car had drifted 6 ft and was hanging off the edge of the driveway, with a film of mud over the body and the motor flooded. The mailbox was just high enough. He pulled the catch to one side and looked in. "We've got mail!" he said, cheered at finding something dry.

Around him, those neighbours who had returned, mostly Hispanic families, played music and shouted to each other as they threw furniture, carpeting and wet sheetrock out onto the front lawns.

Frank stood back and surveyed the damage. They would have to sell up, he said. But about $20,000 in repairs lay between them and a sellable house. "I don't have that kind of money," he said. "That's the point, I don't have the money. And it's hard to go to the bank and borrow money when your house is flooded. They'll tell you you're a risk."

It wasn't so much the money that prevented them getting flood insurance in the first place, said Melvin Lee, Frank's younger brother by seven years. "We just didn't see this coming," he said. "We had no idea it would be this bad. I don't think anyone thought it would be this bad."

Melvin Lee Rogers surveys the damage outside the home he shares with his brother

Five days after the flood washed away his mobile phone, Frank reached his sister. She told him she would collect him and Melvin Lee from the house. They set their few possessions down outside - a handful of dry clothes in a clear plastic bag, and Squeaky, in a carrier donated by the shelter - and began to wait.

Back at the convention centre, Mary and Herman were getting ready to bed down for a sixth night on their cots, surrounded by thousands of others. Mary was making sure to keep her phone charged at the charging station, so she wouldn't miss a call or an email from Fema. They were relieved to have seen the home, they said, despite the state of it.

James was relieved too. It seemed like knowing was better than not knowing, no matter how bad the damage. As he took one last look around his house and got ready to leave, he flicked a light switch absentmindedly. The bulb over the dining table caught him by surprise. "We have light!" he said. "That's a start!"

On the drive back from the house he was upbeat. He told the story of how he first met Rose. "I was fixing her boyfriend's car, so I had my shirt off and in those days I was still pretty well built. Anyway, it wasn't long after that I was working on another guy's car near her house, and she had a nice tree there I could use for pulling motors. She jumped up on the truck to help get some bolts out and that was that."

At the shelter, Rose waited anxiously for James to return. When he found her, he told her about the house. It wasn't bad at all, he said. The glass in the secretary desk was intact and the power was still on. The two dogs next door, which Rose loved, had survived, and the picture of her mother was hanging exactly where she left it. She cried with relief. James took her arm and walked her back to their cots, before getting in line again to speak to Fema. "I can wait another few hours," he said. "I've got time."

.

- Published29 August 2017

- Published29 August 2017

- Published31 August 2017

- Published31 August 2017

- Published30 August 2017

- Published28 August 2017

- Published29 August 2017