Solar eclipse 2017: Chasing the moon's shadow at 40,000ft

- Published

The view from over the Pacific

"It's a complex math problem," said the pilot over coffee and doughnuts at 5am, in what sounded a lot like an understatement.

We would be travelling at 520mph, he explained, while the moon's shadow would be moving at nearly eight times that speed.

In essence, went on Captain Brian Holm, we were going to try to sideswipe a car travelling at 4,000mph.

To do so we would need to fly a total of 2,300 miles from Portland, Oregon, on the US west coast out over the Pacific Ocean and back.

That was the plan as we set off early on Monday morning, not long after the sun's rays had crept over the horizon for a sunrise which drew rather more attention than usual.

There were two reasons for a lengthy trip over sea to hit the tiny eclipse bullseye rather than a short one over land.

First, this would be the lowest point in the sky of the eclipse, giving us the best chance for a decent view from the aircraft windows before the sun rose too high.

Secondly, it would mean we didn't have to worry about the traffic.

Those on the flight included competition winners and experts

In 1979, when a total eclipse touched the states of Oregon and Washington, hundreds of aircraft took to the skies, causing chaos for air traffic controllers. Many hopeful eclipse watchers were disappointed.

Alaska Airlines could not afford for that to happen and this time they had experience on their side.

Two years ago Joe Rao, a TV meteorologist, space columnist and umbraphile (literally a shadow lover, or eclipse enthusiast), emailed the airline asking them to delay flight 870 from Anchorage to Honolulu by half an hour on 8 March 2016 so it would intercept a total eclipse 700 miles north of Hawaii.

The idea was bounced around for months among sceptical executives before Mr Rao and his friends finally convinced the right person, Captain Holm, the Boeing 737 fleet captain for Alaska.

For once, the passengers were delighted about the delay.

This time, flight 9671 - or Solar One as it was dubbed by the cabin crew - was by invitation only; the passengers were a mixture of media, competition winners and scientists, as well as senior staff from the airline and their guests.

The plane took off early to avoid traffic in the skies

The first couple of hours of the flight passed uneventfully but as the moment of totality ticked closer the tension rose.

We were on track to hit the sweet spot, said the pilots, give or take two seconds.

At first the light seemed to dim almost imperceptibly but soon it was undeniable: day was turning to night.

When the total eclipse was nearly upon us time seemed to speed up.

Cameras clicked frantically; solar glasses were pulled on and off and then on again; faces of strangers were suddenly cheek to cheek, pressed against any window with a view.

And suddenly we were there.

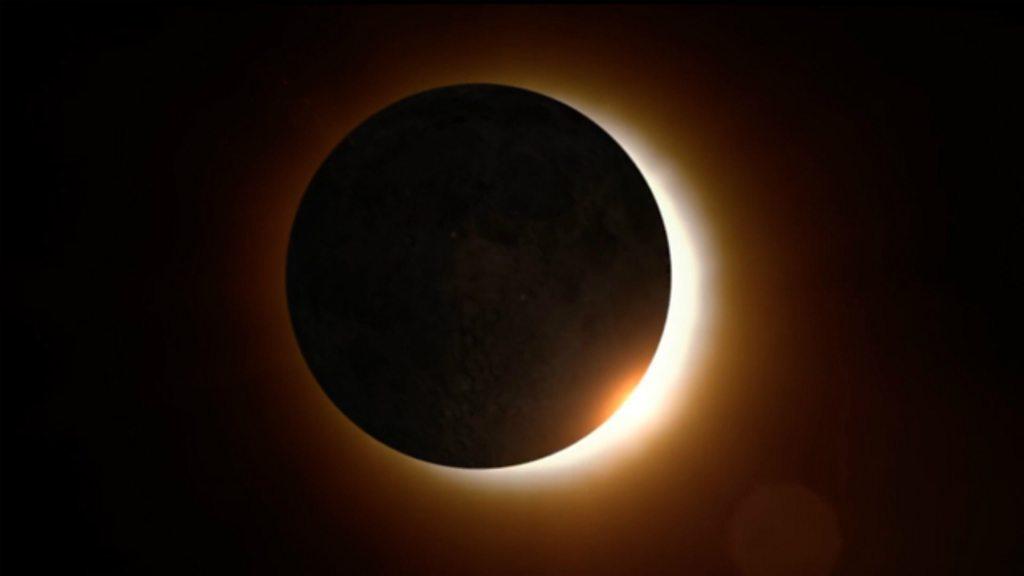

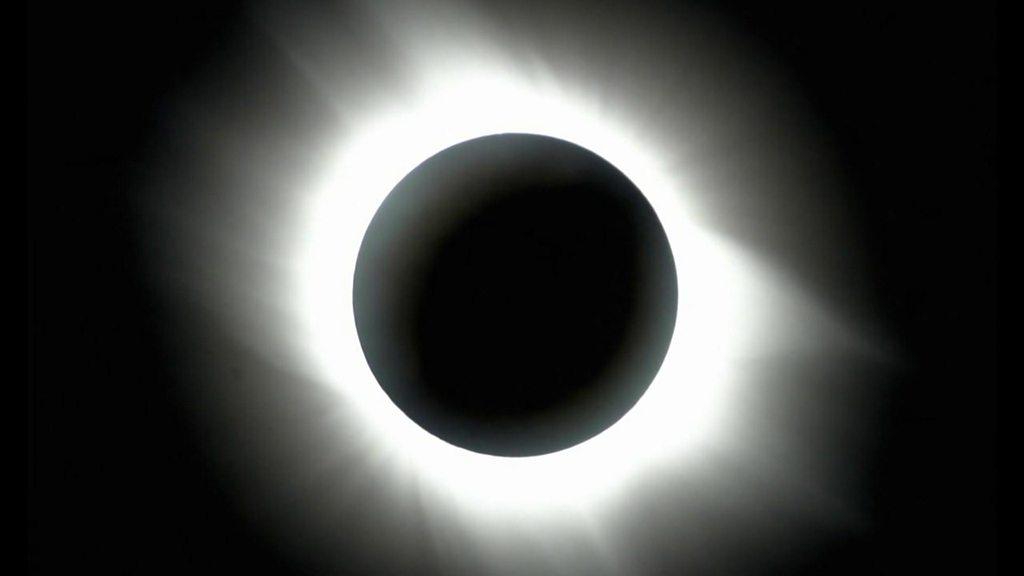

"Totality! Totality!" came the excited announcement on the intercom and through the thick plastic windows on the right hand side of the aircraft the moon looked as if it were a tiny spherical pebble which had been hurled, with beautiful accuracy, straight into the gaping, glaring mouth of our star.

"It's incredible. It's almost indescribable," said Hannah Winit, struggling to put into words the glory and wonder that was unfolding in front of her.

The plane filled with cheers when the eclipse finally happened

"It's really vibrant," she added, "like a sun but not a sun, almost like a flower." Ms Winit and her husband Matt, who both work for Alaska Airlines, said they had won a ticket on the flight in an internal company competition.

And now, suddenly, there was so much to look at and so little time.

From 40,000 feet we could see the enormous curving shadow of our only satellite blotting out the dappled white clouds which blanketed the ocean.

There were gasps and cheers as a flash burst from the side of the moon. "Diamond ring!" came the shout.

Reuben Dragushan, 10, said it was "awesome" to be one of the first people in the world to witness the spectacle.

"It was amazing. It looked like a dark disc and then light coming out of all the sides. It was really cool."

Watch the eclipse in 60 seconds

For 103 seconds it was an eerie and ethereal sight which for some passengers, including Reuben's mum Evgenya Shkolnik, a professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, was accompanied by a wave of emotion.

"Beautiful and poetic," was her description. "Way more beautiful than any photo I've ever seen. It was brighter. It was richer and the colours were even more exciting."

"It was just too short. Oh my goodness, I need another few minutes!"

Maria Rao, from Westchester, New York, on board with her father Joe, the meteorologist, agreed.

"It's breathtaking, it's truly breathtaking and it goes by so fast," she said. "We had a minute and 34 seconds of totality and I swear to God it was only ten seconds!

"Now I'm like 'When's the next one?'"

- Published21 August 2017

- Published21 August 2017

- Published21 August 2017

- Published17 August 2017

- Published18 August 2017