Canada challenge to six-month sobriety rule for liver transplants

- Published

A Canadian man is challenging a long-standing rule that alcoholics must be sober six months before being put on the liver transplant list. But as his court date approaches, is Cary Gallant running out of time?

Cary Gallant has not touched a drop since 8 July, 2017, a mighty achievement for a 45-year-old man who has been an alcoholic since his 20s.

It might not be enough. After being admitted to hospital in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, on 16 July, he was diagnosed with alcoholic liver disease and told that without a transplant, he had a 75% chance of dying within six months, according to documents filed with an Ontario court.

His doctors have refused to consider him for a liver transplant, citing a policy that requires alcoholics to be sober for at least six months before being put on the transplant list.

Mr Gallant's timing is particularly unlucky, as Trillium Gift of Life Network, the agency in charge of Ontario's transplant programme, has already agreed to launch a three-year pilot project in the summer of 2018 lifting the six-month sobriety rule for some patients.

Two people with liver disease talk about the damage caused to their livers

But for Mr Gallant, this summer might as well be an eternity, which is why on Friday he will take his case for a new liver to court. Represented by lawyer Michael Fenrick, he hopes to prove that Trillium's current policy discriminates against him and violates the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada's bill of rights protected by its constitution.

"I think we should be making decisions like this based on the best-available medical evidence, and not outdated views... about who is an appropriate person to receive an organ," says Mr Fenrick.

In a written response to the BBC, Trillium said that "our research on liver listing criteria points to a six month abstinence from alcohol for alcoholic liver disease patients as the most commonly used protocol across Canada, the US and other international jurisdictions".

Although they intend to test removing these restriction in 2018, Trillium said "it is important for all Ontarians to know that the listing criteria for liver transplants remain unchanged" in the interim.

Six-month sobriety rules are common across Canada, in the US, the UK and in Europe, but medical opinion is starting to wane in light of new research.

"Liver transplant policy in the US continues to be driven in most centres by social norms of poor public perception of alcohol addiction," wrote Dr John Fung, chief of transplantation surgery at the University of Chicago Medicine Transplantation Institute, in a statement filed in court on behalf of Mr Gallant.

Dr Fung sites multiple studies that found that there was no difference in survival rate between liver transplant patients with alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) and those without. Studies show ALD transplant patients are also likely to stay sober, with only about 10-20% resuming heavy drinking.

For those with ALD who did die after transplantation, the most common cause of death was not recidivism, but cancers and heart disease associated with a higher rate of smoking.

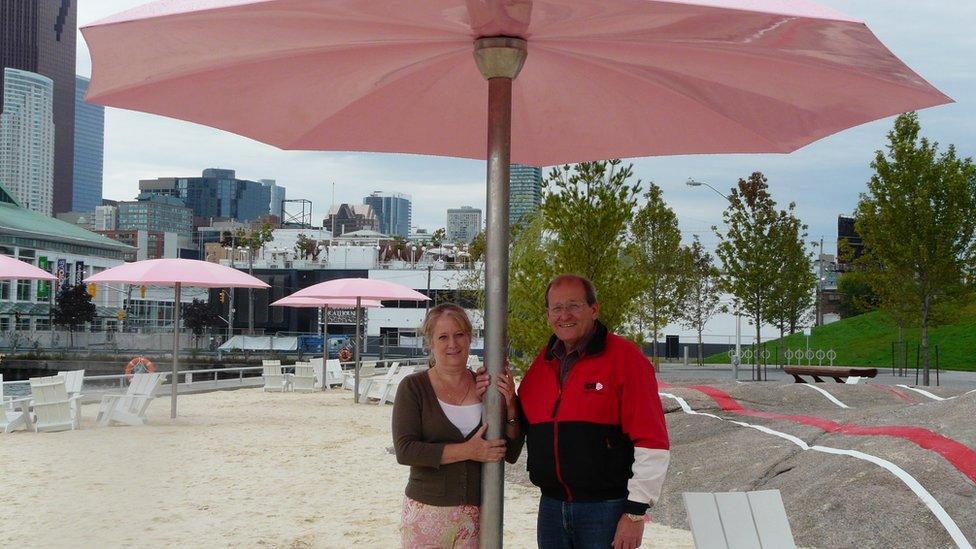

Debra Selkirk and her husband Mark Selkirk

This hopeful prognosis is not what Debra Selkirk was told when she sat in an Ontario hospital with her husband Mark Selkirk in 2010. A heavy drinker for most of his adult life, Mark was told he had very little time left without a liver transplant.

Having only been sober for three weeks, Mr Selkirk was told by a nurse that the transplant agency "would not even look at you".

"They said alcoholics always drink again," says Mrs Selkirk.

Not much more than two weeks later, Mr Selkirk was dead.

"They made you feel like he was a failure," she says. "It made us all feel ashamed that he couldn't control his drinking. So for two years after he died… I'd just say he got sick, because I was ashamed of him too."

That changed when Mrs Selkirk started researching the law, and found medical research that challenged the notion of the six-month sobriety rule. Without legal aid, she launched her own legal challenge against Trillium.

"Now I'm ashamed I was ever ashamed of him," she said.

After meeting them, they said they had re-examined their policy and would create a pilot programme to study removing the six-month challenge.

In documents provided to Mrs Selkirk and shared with the BBC, Trillium agrees that "the evidence supporting the requirement is poor" and that a pilot-programme should be launched to examine a new policy.

They are not the only ones - in 2014, the UK tried its own pilot programme for people with severe alcohol-associated hepatitis and several hospitals in the US have tried similar pilots.

Dr Robert Brown, who specialises in liver transplantation at Weill Cornell Medical College, was one of the doctors who originally advocated for a six-month sobriety rule. He now supports updating the guidelines, but cautions that "we should not throw the baby out with the bathwater".

The intention of the rule was to reduce recidivism, and to make sure that liver transplants were only going to people who could not live without one.

Although advances in science have helped doctors make those predictions more precisely, he said it's vital that any new programme still takes these goals into account.

While Mrs Selkirk is "extremely pleased" about Trillium's pilot, she says she is mystified as to why they are waiting until 2018, when people like Mr Gallant are suffering now.

"If you could save patients today, then why are you waiting until next summer?"

- Published4 April 2014

- Published25 March 2014