The Canadian city where addicts are allowed to inject

- Published

Canada's first supervised injection site fought to stay open

As the opioid crisis spreads across North America, the Canadian city of Vancouver is pioneering a radical approach to drug treatment - let addicts use.

It's "cheque day" in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, and people are feeling good. Having just cashed their monthly social assistance stipend, many residents have flocked to the local street market, where vendors peddle everything from bootlegged DVDs to handmade crafts.

But the marketplace is not the only place where money is changing hands. In the alleyways and squats that pepper the neighbourhood the drug economy is booming, and so are the overdoses.

"You come to work every day and you find out who has died," says Sarah Blyth, a community advocate who runs the street market. "It is extremely depressing."

Heroin has been a part of the Downtown Eastside for as long as most people can remember. By the 1990s, needle-sharing among drug users in the city led to "the most explosive epidemic of HIV ever observed outside of Sub-Saharan Africa," according to Aids researcher Dr Thomas Kerr.

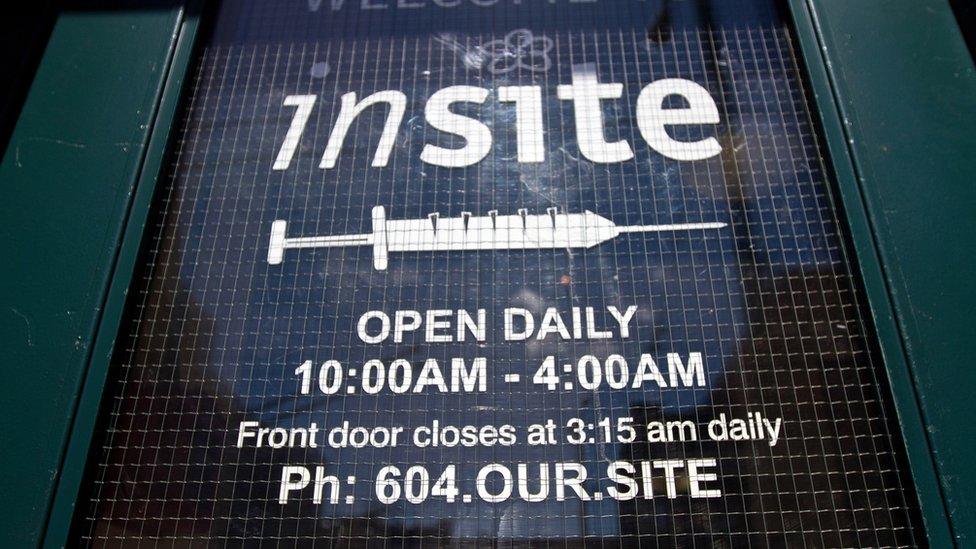

This early drug crisis led to the opening of North America's first supervised injection site, Insite. Now, as an opioid epidemic spreads, the Downtown Eastside has become an incubator for a variety of out-of-the-box drug treatments.

Ground Zero

Insite, the supervised injection site is right across from the market. Since opening its doors in 2003, the clinic has become an integral part of Vancouver's downtown.

The space is gleaming and clinical - a far cry from the popular image of addicts huddled in a dirty alleyway. In June 2017 alone, Insite's injection room was visited about 10,600 times.

In 14 years, no one has died of a drug overdose at Insite or any other supervised injection site in Vancouver.

Founding director Chris Buchner says the facility provides "dignity to people who are not afforded a lot of dignity in their day to day lives".

Mr Buchner began his career as an HIV activist in Montreal, and took on the role at Insite to treat "problematic substance use not as a criminal action or a moral failure but as a health and social issue".

Patients are allowed to inject their own drugs at the clinic, while a nurse or doctor looks on.

Insite helps connect drug users to other social services, like housing and mental-health resources, and provides detox services to help people get clean.

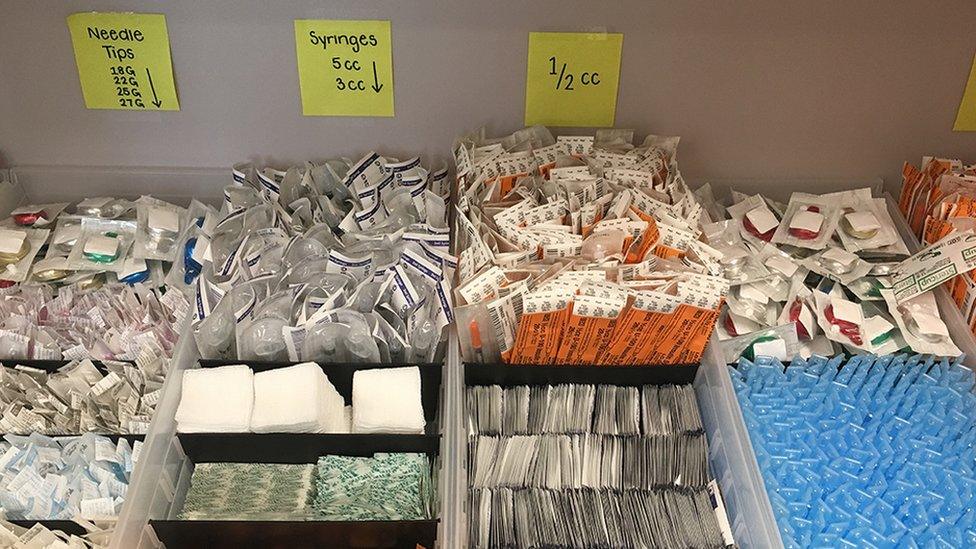

Supplies at a new supervised injection site located in Surrey, BC

Dozens of papers in peer-reviewed journals, including the British Medical Journal and the Lancet, support Insite's claims that such strategies reduce disease and public disorder and can actually help encourage people to get off drugs for good.

This research has helped fuel an interest in opening up similar sites across North America. To date, Health Canada has licensed 16 supervised injection sites across the country. The American city of Seattle also hopes to open a clinic.

Critics have accused Insite of giving up on addicts, but the clinic's current director Dr Mark Lysyshyn believes it is just the opposite.

"It is helping people when they need you, helping them stay alive until they get to the point where treatment or detox is an option for them," he says.

Area 62

But it was the spread of fentanyl, a deadly opioid between 50 and 100 times more powerful than heroin, that turned supervised injection from a medical experiment into a necessity.

A person injects drugs at Area 62, which is run by the Overdose Prevention Society

Nowhere has been hit harder than Vancouver. The city is projected to see 430 overdose deaths in 2017, nearly double from last year.

Blyth remembers when things first started to take a turn, towards the start of 2016. Although overdoses have always been a problem in the alleyway behind the market, she says it got to the point where every morning there would be a new body.

"People were falling down all over the place," she says.

Ms Blyth had been trained in how to administer Naloxone, an antidote to opioid overdoses, when she worked at a homeless shelter in the area. Soon, she found herself running to Insite to grab Naloxone kits every day.

In the fall of 2016, she and a group of volunteers created the Overdose Prevention Society, a grassroots supervised injection site located between the street market and the alleyway, in what is now known as "Area 62". She helped train people to use Naloxone, and started crowdfunding to buy their own supplies.

Sarah Blyth stands outside the Downtown Eastside street market

Unlike Insite, which was granted a special exemption to the federal drug laws by the government, Area 62 was illegal when it first opened. Police turned a blind eye until Christmas 2016, when Vancouver's public health department agreed to issue them a license.

"We just said 'screw it, we are going to have a space'," she says.

"And anyone who says we can't, we are just going to say we are saving lives, bugger off."

The Overdose Prevention Society is run out of trailers and tents. Most of the volunteers are from the area, and are either drug users themselves, or have family members who are.

Blyth says that for many, saving other people's lives helps gives them a reason to stay clean.

"It gives them wind in their sails," she says.

Robin Macintosh, a neighbourhood resident whose brother overdosed in 1993, says volunteering has given her life meaning. She counts the number of lives she's saved in the hundreds.

"This is my baby," she says.

At the crossroads

Just down the street from Area 62 is one of the most heavily guarded stashes of heroin in the city. But it's not a drug dealer's den. Rather, it is Providence Crosstown Clinic, the only medical facility in Canada prescribing heroin to addicts.

Although diacetylmorphine - pure heroin - is prescribed by some UK doctors and in some parts of Europe, Crosstown is the only place in North America that helps addicts get their fix. The programme began in 2009, and is running at capacity with 130 patients.

Russell Cooper says prescription heroin from Providence Crosstown Clinic has saved his life

Russell Cooper is one of them. A big burly guy with a leather vest, he looks like he would fit right in on the set of Sons of Anarchy, but he is patient and soft spoken, and says he understands why people might disagree with the controversial treatment.

"I do not blame them. Why should their tax dollars put out for people to just go get high?" he says after his morning dose.

"All I can say to them is addiction is a very powerful thing."

Mr Cooper has been using for 30 years, since he tried heroin for the first time while in prison.

It made him feel good - he liked it, and his friends used it. But when his fix wore off, he was left shaking and sweating, with only one thing on his mind - where could he find more heroin.

When he got out of prison, he started dealing drugs to support his habit. He lost custody of his son and stayed in homeless shelters. He tried methadone treatment multiple times, sometimes going one or two whole years without using.

But he always came back.

"The methadone is kind of just putting a blanket over it but sooner or later, you are going to start getting cold," he says.

Cooper is the ideal candidate for this kind of programme, says Dr Scott MacDonald, lead physician at Crosstown. Prescription heroin is a last resort for people who have tried to quit many times before.

Like Insite, Crosstown also connects people to social services in the city. That's really its purpose, says Dr MacDonald. By giving them stable doses of clean drugs, without the toxic fentanyl, addicts will be able to maintain their addiction and stay off the streets.

Mr Cooper believes the programme has saved his life.

He is out of a homeless shelter and living in his own apartment. He makes some money doing odd jobs in his building and helping a friend who works with racehorses. And he volunteers to go to children's schools, and educate them about the dangers of opioids.

"It could not be better. Things you never thought you would get," he says.

The one thing he wants most is to reconnect with his 12-year-old son.

"The questions are starting to get harder and harder to answer," he says.

"I talked to his mom about it and she said the best thing for you to do is be honest."

Bridge to nowhere?

Despite the number of addiction programmes in Vancouver, the rise of fentanyl-related deaths means health officials are always playing catch up.

"It feels a little bit like a bridge to nowhere sometimes," says Mr Buchner.

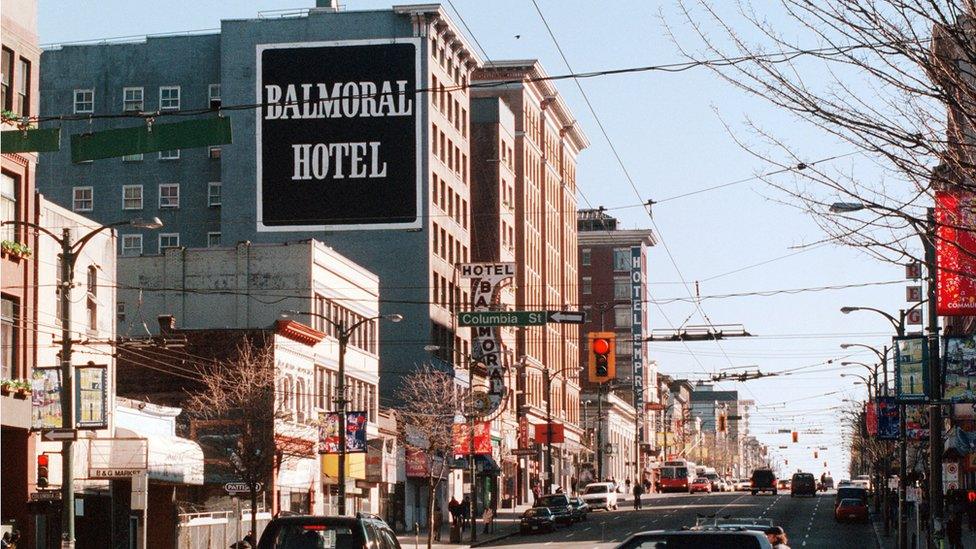

Vancouver's downtown eastside

He now works for suburban public health authority, Fraser Health, and says programmes that work in Downtown Eastside won't be as effective elsewhere.

"Unlike in Vancouver, where the vast majority of overdoses are centralised in five square blocks, in other communities they are spread out," he says.

Most overdose deaths occur when someone takes drugs alone in their apartment, public health data shows, which means it's vital to connect with people before they use.

Fraser Health has been deploying nurses to areas where there has been overdoses in the past, to distribute Naloxone kits and supervise injections in people's homes.

But Mr Buchner says governments also need to invest in stable housing, mental health resources and education, so that people don't feel the need to use to begin with, he says.

"We can keep people alive, but when we keep people alive just to overdose again, why will we not build them housing?"

Dr Lysyshyn agrees the overdoses will slow when drug addicts are not treated as moral failures.

"We will never be able to supervise all the injections," he says. "So ultimately the strategies about preventing this are not about Naloxone, they are about changing drug policy."

- Published17 December 2016

- Published1 August 2017

- Published1 August 2017