Bombardier turns to Europe in turbulent US trade row

- Published

Parts for Bombardier's C-Series planes are made in Belfast

Canadian company Bombardier has been a thorn in the side of UK Prime Minister Theresa May since the company became embroiled in a vicious US trade dispute. Could selling to Europe solve everyone's problems?

It is not an easy time to be a politician in Northern Ireland.

Stormont has been without a devolved government since January, when a coalition led by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Fein collapsed.

Meanwhile, the region is also faced with Brexit negotiations, and what that means for its border with the Republic of Ireland, which is still a part of the European Union.

This political quagmire is strong enough to stretch all the way to London, where UK Prime Minister Theresa May has had to form an alliance with the DUP in order to keep her Conservative Party in power after losing its majority in June's election.

The last thing Mrs May needed on her plate was a trade dispute between two foreign governments causing an economic problem at home.

But that is almost exactly what happened.

In early October, a trade dispute between US airplane manufacturer Boeing and its rival, the Canadian company Bombardier, came to a head when the US Department of Commerce imposed a 300% tariff on Bombardier's flagship product, the CSeries jet.

Boeing complained that government subsidies had enabled its competitor to sell the CSeries jet for less than the cost to make it, giving the company an unfair competitive advantage.

The dispute was unsurprisingly big news in Canada, where local governments have sunk hundreds of millions of dollars into the success of the CSeries and the company's future.

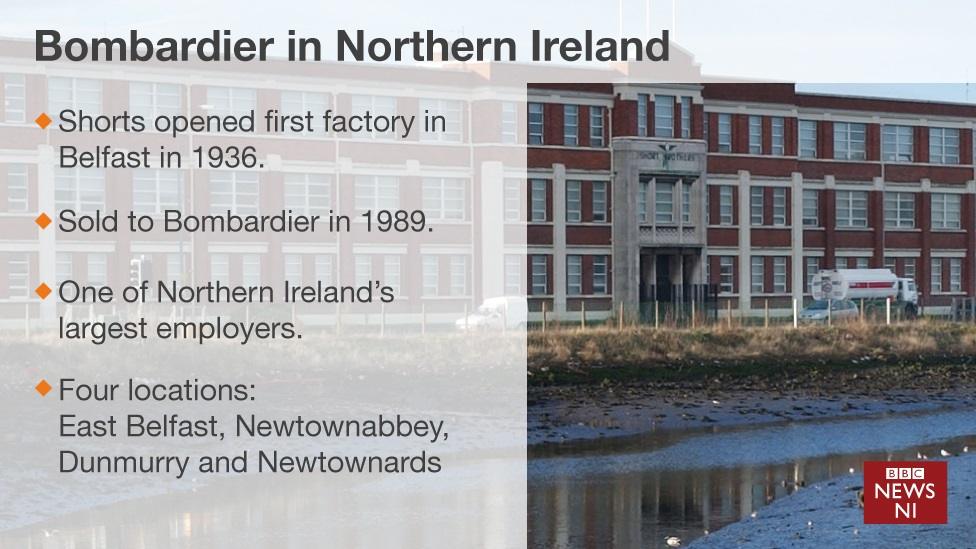

But it also elicited a strong reaction in Northern Ireland, where the company builds the wings for the CSeries.

"It is a massive part of Northern Ireland's economy, it can not really be understated," says Andrew Webb, an economic analyst in Belfast for Webb Advisory.

The company currently employs about 4,100 people in Northern Ireland, and generates about £200m (C$329m; $264m) annually in earned income. About a quarter of Bombardier employees are working on the CSeries.

"The future of the CSeries will have a significant bearing on the future of Bombardier in Belfast," Mr Webb says.

The threats to the CSeries elicited cries of outrage from both leaders of DUP and Sinn Fein as well as the foreign affairs minister for the Republic of Ireland, who warned Washington the stiff duties could risk peace in Northern Ireland.

But a strong response also came from Mrs May herself, who phoned Donald Trump to discuss the issu.

Her defence secretary, Michael Fallon, has also warned Boeing its behaviour "could jeopardise" future defence contracts.

Mrs May's willingness to join the fray may have more to do with uncertainty within her own Conservative Party than with the threat of civil strife in Northern Ireland, says Steven McGuire, a political economist and director of the school of management at the University of Sussex.

UK PM Theresa May had to tackle the Boeing-Bombardier trade dispute

"Theresa May doesn't need more difficulties in Northern Ireland as she negotiates Brexit," he adds.

"If she could get this off the table, I am sure she would want to."

It looks like she just might. Bombardier on Monday night announced a deal with another rival, the European company Airbus.

Airbus will get a 50.01% stake in the CSeries, and in exchange, it will help get the plane to markets around the world.

The wings will still be made in Northern Ireland, but planes bound for US markets will be assembled at Airbus' US plant in Alabama, which could help the companies avoid US duties.

The deal has been heralded as a win-win for both the company and Belfast. It is also likely a weight off of Mrs May's shoulders, Mr McGuire says.

"It gives her for the time being, one less headache," he says.

But in the long term, jobs in Northern Ireland may still be at risk if Britain cannot negotiate a trade deal before it leaves the EU, Mr McGuire says.

The deal between Bombardier and Airbus means that the future of one of the most important aerospace companies in the UK is now largely in the hands of a European company.

Airbus has factories all over Europe - including Wales - and if a trade deal with the EU cannot be reached, it could lead to questions as to whether it will continue production in the UK.

"Airbus' official line is it wants as frictionless trade as possible," Mr McGuire says. "But I think more and more, companies are contemplating a more disruptive Brexit, and they will have to make decisions about… where they put their future investment."

- Published13 October 2017

- Published26 September 2017

- Published26 September 2017