Who are the poor Americans?

- Published

Millions of jobs have been created in the US economy, but many Americans still live in poverty. Who are they?

For nearly six years, the US economy has been generating huge numbers of jobs: nearly two million a year.

Not only has the economic recovery replaced the total number of jobs lost during the Great Recession - which followed the bursting of the housing bubble in 2007 - but it has added enough to account for a growing population as well.

Unemployment in the US now stands at just 4.1%, the lowest since 2000, external, but there are many households which have not seen their fortunes improve.

In 2016 nearly 41 million people, or 13% of the population, were living in poverty, external - down from 15% at the height of the recession in 2010.

So, who are those classed as living in poverty?

In the US, the median income for a four-person household is $91,000 (£68,000).

However, using the official measure of poverty, external, based on pre-tax income and nutritional needs, families of four in poverty have a household income of less than $24,300, external (£18,200) each year.

This may sound high when compared with countries that the World Bank classifies as lower middle income, external - those with Gross National Income per capita between $1,000 (£760) and $4,000 (£3,100).

But both the high cost of living in the US and the growing gap between themselves and the middle classes can result in difficult lives for poor Americans.

In addition, the median income of families living in poverty is well below the poverty threshold, at only $9,600 (£7,200) per year.

Of those living in poverty, the 2016 figures show that there are about 13.3 million children - 18% of those under the age of 18.

As the population has aged, the number of over-65s in poverty has increased to 4.6 million but, at 9%, the poverty rate is lower than for those of working age (18-64).

It is this working-age group which provides perhaps the most striking picture, with nearly 23 million - or almost 12% - living in poverty.

The Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution, external has been exploring this puzzle.

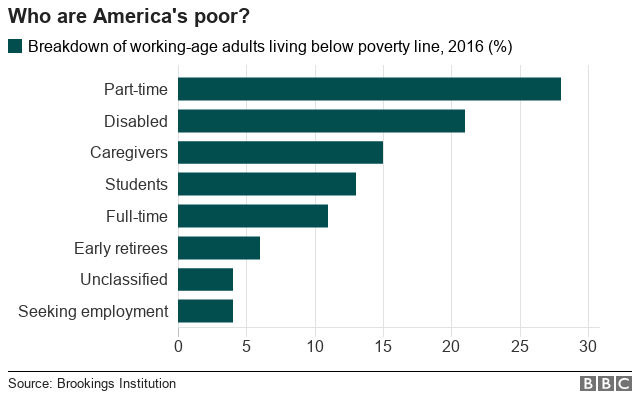

Among the working-age group we found that:

Four in 10 were working

One in 10 had full-time, year-round employment, but did not earn enough

One in four were employed, but not year-round

One in 25 was seeking employment

Of those who were working but without full-time, year-round work, one in three works part-time involuntarily

The fact that roughly four out of 10 working-age adults in poverty are employed highlights the fact that simply closing what we have called "the jobs gap" - returning to the pre-recession employment level after adjusting for population growth and aging - does not mean that everyone is thriving.

It also does not mean everyone finds, or takes up, employment.

The fact remains that well over half of working-age adults in poverty are not in the labour force.

Of the jobs created, many are in hospitality, management, healthcare and IT, although some of the areas hit hardest by the recession - like construction and manufacturing - have not yet fully recovered.

A picture of the US workforce reveals a number of differences across society:

The employment rate for women has returned to pre-recession levels (55%)

Black Americans were hit harder by the recession, recovered faster, but are still more likely to be unemployed than white Americans

Women with a high school education or less are most likely to be out of the work force

Men were hit hardest during the recession and their return to work has been slower (66% now work)

The number of men aged 25-54 who are employed has been falling for more than 50 years and for women since 2000.

In part, this may be a consequence of falling real wages among the lowest earners, with median personal income now $31,100 (£23,200).

It is possible that many of those who are not in the workforce would have difficulty finding employment without significant government intervention.

More than a fifth of those of working-age who are living in poverty are classified as disabled and another 15% are caregivers.

Moving more carers into employment may require improved childcare availability and funding, while many disabled adults may need more support or treatment.

The picture we have built of work and poverty in the US reveals that the poorest are a diverse group, with a wide range of experiences.

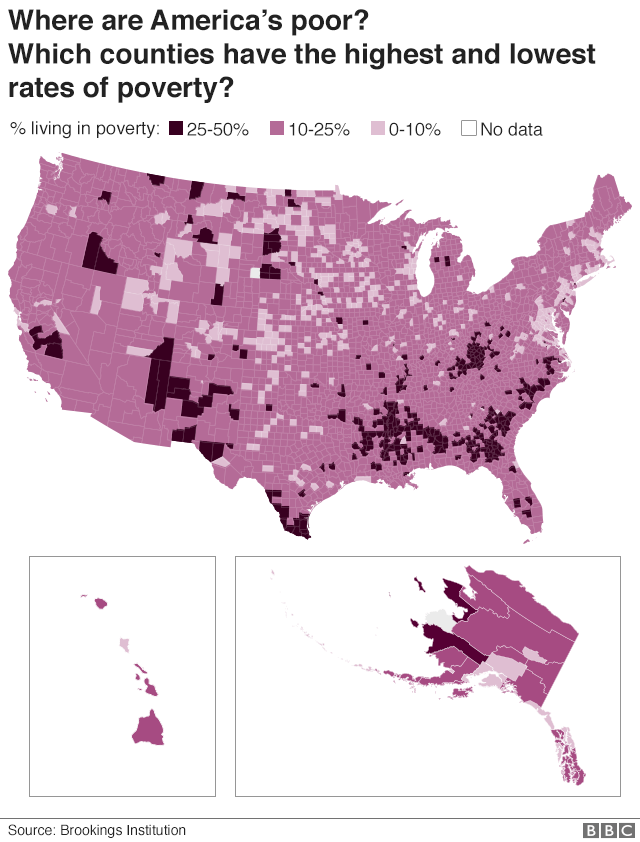

Nonetheless, the unequal distribution of poverty is striking:

Twice as many African American families are in poverty (22%) than white families

19% of Hispanic families are in poverty

Women (14%) are more likely to be in poverty than men (11%)

Poverty rates range from 11% to 14% across large regions of the Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, and West

Many counties - mainly in the Southeast and Southwest - have poverty rates of more than 25%

In recent years, rising employment and incomes, along with falling poverty, have been encouraging.

However, the economy will need to sustain this growth to help more of those who are struggling.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Prof Jay Shambaugh, external is the director of The Hamilton Project and a senior fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution.

The Brookings Institution, external describes itself as a not-for-profit public policy organisation, conducting research that leads to new ideas for problems facing society.

Edited by Duncan Walker