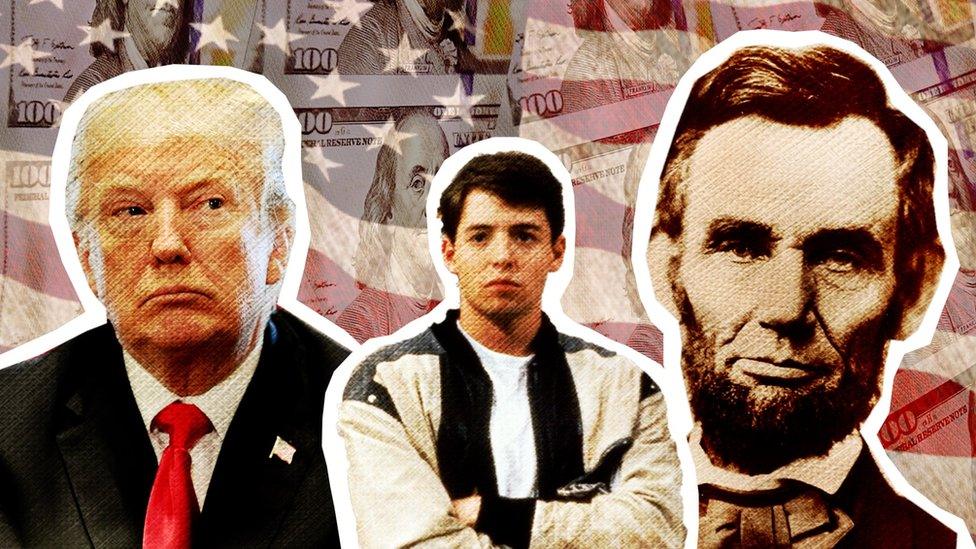

What Trump has in common with Abe Lincoln and Ferris Bueller

- Published

Critics may carp that Donald Trump skipped economics class, like a certain 1980s movie truant. But as the 45th president himself notes, Abraham Lincoln and other historic Republican leaders loved tariffs.

"This bill is an American bill. It is made for the American people and for American interests."

That sounds like President Trump.

But it's William McKinley - another "America First" Republican president - on his Tariff Act of 1890.

When McKinley slapped high duties on US imports, some fellow conservatives thought the powerful Ohio congressman dubbed the "Napoleon of Protection" had gone too far.

"It is the most shameful measure ever proposed to a civilised people," fumed Secretary of State James Blaine. "Go on with it and it will carry our nation to perdition."

White House economic adviser Gary Cohn might well echo that view in regard to current policy.

Cohn, a Democrat, is to quit after losing a battle against Trump's tariff. Congressional Republicans are also imploring the president to drop the plan.

Trump takes a parting shot at 'Globalist Gary'

But despite the outcry, Trump has pointed out that raising the economic drawbridge is thoroughly in keeping with his party's historical roots. It wasn't just McKinley who believed protectionism key to American greatness.

Tariffs were the Republican creed from the Civil War to the Great Depression, and a fundamental doctrine of its preceding party, the Whigs.

Going even further back, the first US Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, now a Broadway musical hero, pioneered tariffs to protect infant American industries from foreign competition. So did fellow Founding Father James Madison.

Republicans from the mid-19th Century onwards continued to champion this fiscal firewall so northern manufacturers could compete with European imports, according to Charles Hankla, professor of political science at Georgia State University.

Democrats, he says, espoused free trade as they were aligned with southern slave-owning plantations that exported cotton to British mills.

It was Abraham Lincoln who inaugurated the Republican party's economic nationalism. Yes, the Great Emancipator was also the Great Protectionist.

"Give us a protective tariff and we will have the greatest nation on earth," he said in 1844.

While Trump is sometimes accused of economic illiteracy, Abe himself once apparently exhibited a flimsy grasp of his pet policy while campaigning for Congress in Illinois.

Tariffs would only be collected from "those whose pride, whose abundance of means, prompt them to spurn the manufacturers of our own country and strut in British cloaks and coats and pantaloons", he insisted, according to a biography of him by David Herbert Donald.

Lincoln didn't have a quick answer for why import tariffs would make things cheaper

A journalist challenged Lincoln on the stump to explain why he thought these duties would make everything cheaper for farmers. The candidate is said to have replied that he "could not tell the reason, but it was so".

Theodore Roosevelt was another Republican president who extolled tariffs as a buttress to American power, according to a biography of him by Edmund Morris.

In 1895, the Rough Rider wrote: "In this country pernicious indulgence in the doctrine of free trade seems inevitably to produce fatty degeneration of the moral fibre."

Despite protectionism's naysayers, the Gilded Age was one of fabulous prosperity.

Political scientists still debate whether the boom was helped or hindered by all those import taxes.

It took two world wars and an international economic cataclysm in the first half of the 20th Century to convert conservatives to free trade.

Heather Cox Richardson, author of To Make Men Free: a History of the Republican Party, says: "All of the people coming out of the [Great] Depression and World War Two are terrified of starting that again.

"So Republicans and Democrats actually begin to look very much alike in terms of their economic policies."

Trump announces steel tariffs on Thursday - with a portrait of Theodore Roosevelt behind him

In the 1950s, Republican President Dwight Eisenhower unabashedly touted free trade as a means to bind the West together in a bulwark against communism. By doing so, he ushered in the modern era of globalisation.

Every Republican leader since has been a pragmatic free trader, even if the siren song of populism has at times proved too potent to resist.

Richard Nixon experimented with duties on imports. Ronald Reagan slapped a tariff on Japanese motorcycles. George W Bush targeted steel imports, only to back down after the World Trade Organization threatened sanctions.

Bush's trade debacle confirmed the worst fears of many grassroots conservatives.

Some Republicans have been deeply suspicious of multilateral agreements since the aftermath of World War One, says Richardson, a history professor at Boston College.

They fretted that these pacts would establish "One World Order, that free traders were going to destroy America by letting foreigners come in and call the shots".

"There was also resentment among people who believed they were being left behind in the post-World War Two order," she adds. "And that is the concept Donald Trump capitalised on."

One result of Trump's recent policy is that a notorious 1930 trade law - remembered in popular culture for its amusing cameo in a cinema classic - is back in the spotlight.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, a Republican measure that imposed hundreds of import duties, is generally agreed to have worsened the Great Depression.

In the 1986 movie Ferris Bueller's Day Off, this bill is the subject of a lecture to catatonically bored high school students.

Trump constantly worries about the trade deficit - should we?

The film's hero - an affluent child of Reagan's Morning in America - had skipped class.

Trump's critics argue that he has not learned the lesson of Smoot-Hawley either.

They warn he risks reigniting the beggar-thy-neighbour trade wars waged amid the ruination of the global economy nine decades ago.

The multi-billion dollar question is, when and where will Trump's tariff end?

It's anyone's guess.

Or as Ferris Bueller's monotonous teacher, external would say: "Anyone? Anyone?"