The place that tells you everything about US politics

- Published

Beto O'Rourke and Will Hurd are Texas congressmen on opposite sides of the political divide who formed an unusual friendship a year ago during a road trip that was broadcast to millions. But with looming elections threatening them both, American voters might show they want confrontation over co-operation.

It was the most unexpected of road trips, like a low-budget, made-for-cable buddy film. Democrat O'Rourke and Republican Hurd, both US congressmen representing west Texas districts, were stuck in their home state due to an East Coast snowstorm. It was Monday, and they had to be in Washington for scheduled votes by Wednesday.

No flights? No problem. The two piled into a rented Chevy Impala and made the 30-hour drive, stopping for a few hours in Tennessee for a visit to Graceland and a quick nap.

"That was a really fun, honest, real thing because nobody planned it," O'Rourke says with a laugh, looking back on the year anniversary of that 2017 odyssey. "Nobody cooked it up. It was just, hey, Will, both of our flights got snowed in, how about we drive across the country? And Will called my bluff."

The two broadcast the whole thing on social media, taking questions, singing songs and sharing snacks along the way. The trip became a viral sensation, and by the end of it the two congressmen pledged that they had learned important lessons about what's wrong with US politics and how they could help make it right.

Why are this Republican and Democrat on the road together?

"Here was my takeaway from this, and it's still valuable to this day," Hurd tells me. "Way more unites us than divides us. The American people want to see us be able to disagree without being disagreeable."

O'Rourke notes that the best memories of the trip weren't necessarily when the two spoke about politics - trade, Russia, healthcare or immigration - it was the personal moments. They swapped stories about their first girlfriends and their taste in music; how they learned to drive and what kind of food they liked.

"It's the kind of civil conversations that are so unusual today between Democrats and Republicans because they just aren't happening," O'Rourke says. "And I think that's what we all in this country are missing. Just the dignity and the decency and the courtesy of hearing each other out and being civil to one another."

Both congressmen have incorporated this language of bipartisanship and togetherness into their politics and are using it in their 2018 political campaigns. It's a bit of an irony, because politics - at least the way it works in Texas, the way the game is played throughout the US - is trying to tear them apart.

Hurd faces an uphill fight to win re-election in a Texas congressional district that increasingly tilts to the left. Two years ago, he won there by only 1.3%, while Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton beat Donald Trump by four points. It tops the list of pick-up targets for Democrats hoping to win the 23 additional seats necessary to take control of the US House of Representatives.

O'Rourke, meanwhile, has higher ambitions. He is the Democratic nominee to run against Republican incumbent Ted Cruz for one of Texas' two US Senate seats. He faces even longer odds than Hurd, as no Democrat has won a statewide race in conservative Texas in more than two decades.

It's hard to envision a scenario where Hurd and O'Rourke both head back to Congress in January. Based on special election results, generic congressional ballot polls and historical trends, Democrats are in for a successful mid-term election. A wave is on the horizon - and O'Rourke and Hurd sit on either end of it.

If it's a cataclysmic electoral event, O'Rourke could beat Cruz and be swept into the Senate. In such a case, Hurd would almost certainly go down to defeat. If November is an electoral ripple instead of a tide, and Hurd prevails, it's next to impossible to envision an outcome where O'Rourke also winds up on top.

One scenario ends with Republicans maintaining a hold on Congress and two more years of unified party reign under President Donald Trump. The other could lead to Democrats in power in the House and the Senate, and a chastened president facing new scrutiny from resurgent political opponents.

This is a battle that will play out in contests across the US, but the struggle in Texas - the struggles of Beto O'Rourke and Will Hurd - illustrate the larger conflict.

'Beers with Beto'

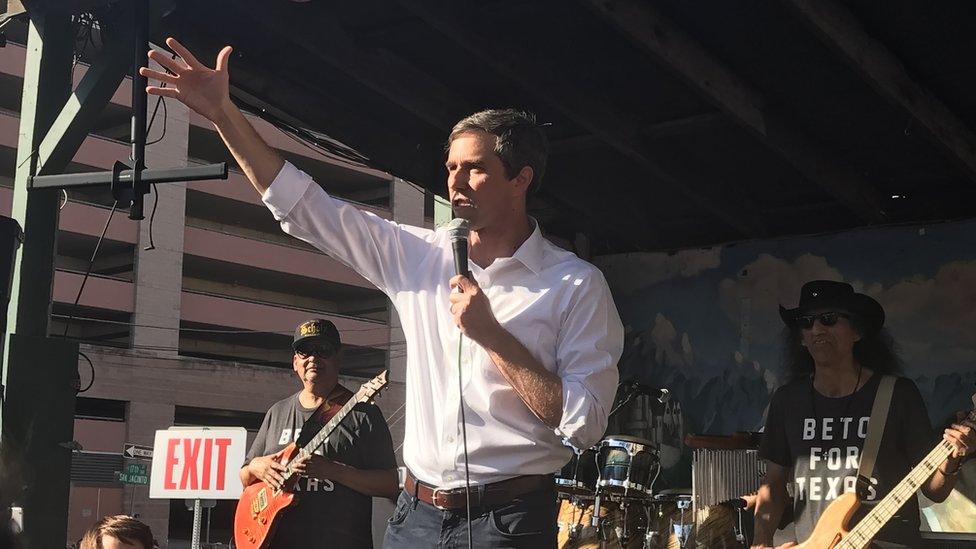

It's a scorching mid-March afternoon in Austin, Texas, and O'Rourke is giving a speech and answering audience questions at Scholz Garten, a long-time watering hole for politicians and dealmakers near the state capitol building.

The 45-year-old congressman stands on stage, his sleeves rolled up and sweat beading on his forehead, as he switches seamlessly between English and Spanish.

The crowd chants "Beto! Beto!" - the Hispanic diminutive for Robert, O'Rourke's given first name, that he has gone by since he was a child.

Just a few days earlier the descendent of Irish immigrants who grew up in the US-Mexico border-town melange of El Paso easily won his primary for the Democratic Senate nomination. Already his Republican opponent, Cruz, has launched a blistering attack against him, accusing him of being a big-government socialist who wants open borders, higher taxes and gun confiscation.

On stage at Scholz, however, O'Rourke doesn't even mention his opponent. Instead, there's more talk about bringing the state together.

"Wherever you are, you're one of us," he says after rattling off a list of towns in Texas, large and small. "All 28 million of us. Human beings, Americans, Texans before we're Republicans before we're Democrats before we're independents. We're going to do this together."

It's not a bad rhetorical twist, given the strength of the Republican Party in the state. If O'Rourke is going to win, he'll have to do one of two things - either bring people to the polls who have never voted before or convince disaffected Republicans to give him a try. O'Rourke is trying a little of both.

The candidate also takes some shots at Trump who, thanks to his immigration and anti-trade stances, isn't particularly popular in the state.

More than that, however, O'Rourke is running as a reform candidate. He has turned down all corporate political action committee (PAC) donations, eschewed pollsters and high-paid campaign consultants, and is relying on small donations to finance his bid in a state with some of the largest media markets in the US.

More from Anthony:

O'Rourke rallies and "town hall" forums are rollicking affairs. There's often music - the Scholz warm-up band was Tejano rocker Little Joe and La Familia - and adult libations. Some events are billed as "beers with Beto", where attendees receive a drink ticket in exchange for a small donation to the campaign.

O'Rourke himself is a former punk rocker who cut a few albums and toured the US as the bass guitarist in the band Foss. He's still got a bit of that rocker edge, sprinkling some choice obscenities into his speeches and even media interviews.

He's pledged to campaign in every one of the 254 counties in the largest state in the contiguous US - roughly the size of Germany - and has visited 226 so far. Liberal Austin is friendly territory, but O'Rourke says his campaign message is the same no matter the audience. The important thing, he says, is showing up and listening.

"He's going to areas that are deeply, deeply Republican and trying to talk and relate to people," says Taylor Preston, a graphics designer who attended the O'Rourke rally. "He might not sway them to vote for him, but he's listening to them and he hears them - and that's the way that politics should be. Ted Cruz is not coming to Austin to listen to us or hear us."

O'Rourke's opposite

O'Rourke is, in many ways, a mirror image of his Republican opponent Cruz - the son of a Cuban immigrant who opted for an Anglicised name, Ted, instead of his given one, Rafael. Where O'Rourke has emotion, the Princeton- and Harvard-educated Cruz has the methodical manner of an Ivy League corporate lawyer.

Where O'Rourke is socially liberal (he supports legalised marijuana, gay marriage and abortion rights), Cruz campaigns as an evangelical conservative. Where O'Rourke has a natural charisma, Cruz - while he has a devoted following - can seem more ill at ease among the crowds.

Cruz was also a decided long-shot when he won his Senate seat in 2012, beating a better-funded, better-known Republican in the primaries. Since then, however, he's become a political juggernaut - making a name for himself as a conservative thorn in the side of his party's congressional leadership and building a national fund-raising network that fuelled him to a second-place finish behind Trump in the 2016 Republican presidential nomination race.

Although O'Rourke shocked many veteran political hands when he announced he raised $6.7m in small donations over the first three months of 2018, there's little doubt that Cruz - who has brought in more than $17m since 2013 - will enter the autumn contest against the Democrat with a financial and organisational advantage.

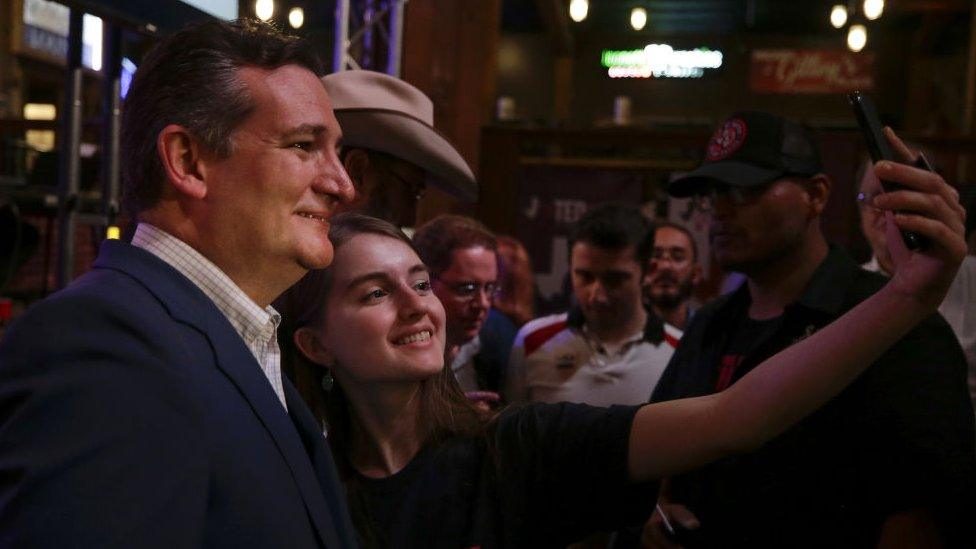

Ted Cruz and a supporter

O'Rourke tells me that he plans to beat Cruz by turning his national brand against him. He notes they were both elected for the first time in 2012, and since then he has spent his time listening to Texans, while Cruz campaigned for president in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina.

"He chose that office instead of the people of Texas, and that's not lost on those in Texas," O'Rourke says.

"Do we want someone who is accountable, who serves the people of Texas, who doesn't take PAC money, who is not compromised by special interests or corporations? Or someone who used his position of public trust to pursue the presidency and did so with $300,000 from the NRA, who takes money from PACs and corporations, and has failed to serve the people of Texas?"

When O'Rourke does start to go after his opponent, expect lines like that again and again.

The Senate at stake

The Texas Senate race is just one of 35 seats up for election in November, but it could end up being pivotal in determining who controls the upper chamber of Congress.

While Republicans currently have a narrow 51-49 advantage, Democrats are defending nine seats in states won by Trump in 2016. Republicans, on the other hand, only have one incumbent trying to win re-election in a Clinton state, Nevada.

There's an open seat currently held by Republican Jeff Flake in Arizona that could be in play, but after that Texas may be as good as it gets for the Democrats. If O'Rourke pulls the upset win, they don't have to sweep to victory in all the other close races (a 50-50 Senate means Republicans maintain control due to Vice-President Mike Pence's tie-breaking vote).

"I don't see Texas in terms of party or colour," O'Rourke says. "I'm not into the blue wave deal, or turning Texas blue."

O'Rourke may not be thinking about a blue Democratic wave, but he probably needs it. And the party - if it hopes for a Senate majority that can block Trump's judicial nominees and pass progressive legislation - may very well need him.

Shelter from the storm

While O'Rourke criss-crosses the state, Will Hurd is keeping a lower profile. The 40-year-old ex-CIA officer who once managed covert operations in Afghanistan is a regular on the Washington political talk show circuit thanks to his seat on the House Intelligence Committee, but he clearly wants this race to focus on local issues, sheltered from what could be prevailing (anti-Republican) political winds.

"I do not believe in national trends," Hurd says during a public event hosted by Politico at Austin's South by Southwest music, film and technology festival. "I do not believe in coattails. When people go in to vote for me, they're voting on what I have done or what I have not done. And if you put yourself in that position, then you're going to be fine. If you don't put yourself in that position, that's where a potential national wave can hit you. "

Will Hurd on the night of his election

Hurd touts his "gold standard" constituent service for those living in his congressional district, which stretches from the suburbs of San Antonio south all the way to 820 miles of the Mexican border and the outskirts of O'Rourke's El Paso. The district is roughly the size of South Korea.

Every August he goes on a "DC2DQ" tour, holding dozens of informal town halls at community centres and Dairy Queens (hence the DQ), an ice-cream-centric fast food chain popular in small Texas towns like Ozona, Kermit and Carrizo Springs.

He talks about what's going on in Washington, DC, but most of what he says he hears - most of what he tries to help his voters with - are the smaller, everyday problems they face.

"We often forget, most people in DC think about big pieces of legislation, you think about putting together coalitions, but most of what we do is battling bureaucracy for people who need it fought against," he says.

"Whether it's [veterans'] claims, or doing something with Medicare, or helping a small business get access selling to the government, those are the actual questions that come up more than not."

In 2016, Hurd was the first incumbent to win re-election in the 23rd Texas congressional district in 12 years. It had flipped back and forth between the two parties every two years prior to that.

The longer legislators represent a district, the deeper roots they can put down - building relationships with voters that transcend partisanship.

Hurd's predecessors had been small trees, easily toppled by each passing electoral storm. Now seeking his third term in Congress, Hurd hopes he's built to survive.

'Guilt by association'

The storm that's brewing could be a big one, however, and it has a name - Donald Trump - whose low favourability ratings and penchant for controversy has motivated his political opponents.

Stacie Sanchez Hare, a San Antonio social worker who plans on voting against Hurd in November, is evidence of that. She says the Republican congressman may talk like a moderate, but he is "guilty by association".

"I felt a black cloud move over me the day after the election, and I felt like I could either let it swallow me or do something about it," she says. "So I started looking up candidates and volunteering, and it's made me feel better."

Will Hurd at a military parade at Joint Base San Antonio

Hare and other Democrats in Hurd's district and across the US are motivated, and they plan to vote in November. "They will crawl over broken glass" to get to the polls, Ted Cruz warned a group of Houston Republicans in February.

When it comes time to talk about Trump, Hurd - the child of a mixed-race marriage - is visibly uncomfortable. He's asked what he thought of the president saying a black Democratic congresswoman has a "low IQ", and he pauses, then says he wouldn't want the children in his family talking that way.

"The way we talk matters," he adds.

Hurd didn't endorse the Republican nominee in 2016, and he's seemingly uninterested in his support two years later.

"I welcome support from everyone," Hurd says to laughs, adding that he agrees with the president sometimes and disagrees at others. "Just be authentic and be real. That's why I got re-elected in a pretty nasty environment, and that's why it's going to happen again in November."

A tale of two novices

Hurd may express confidence, but Democratic opponents are licking their chops at the prospect of unseating him. Five candidates vied to be their party's nominee to take on the congressmen, and on primary night earlier in March, two - both political neophytes - advanced to a run-off election in late May.

The top finisher, with 41%, was Gina Ortiz Jones, an ex-Air Force officer who would be the first Iraq War veteran in Congress from Texas and the first who is openly gay. Rick Trevino, who quit his job as a schoolteacher to run for office, finished second with 17%.

At an election night party in San Antonio, Jones explained why she - like many other first-time Democratic candidates this year - was motivated by Donald Trump's election to enter politics.

Gina Ortiz Jones greets supporters at a campaign event

"I've been in national security for 14 years," she says.

"I've seen what happens in countries where women and minorities are targeted. I've seen what it looks like when governments disregard the conflicts of interest that have hollowed out those countries. So to think how that could be affecting now my country and my community, I wanted to step up and serve in a different way."

Since announcing her candidacy, Jones has been a bit of a celebrity. She was interviewed on the late-night cable comedy programme The Daily Show, was profiled in Teen Vogue and included on the cover of Time Magazine as part of a story on "The Avengers", external - women who marched in Washington after Trump's inauguration and are now running for office.

Jones says she knows what's at stake in her race and that Hurd, while he may be a "nice person", doesn't reflect the views of his constituents.

"Frankly, people know that flipping this district, a district that Hillary won, is going to be key to flipping the House," she says.

Part of the Democratic Party's strategy for taking advantage of a potential anti-Trump wave is to field as many newcomer candidates with compelling personal stories as they can. Jones is a first-generation Filipino-American who grew up in a poor, single-mother family and paid for college with a military scholarship. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC), which helps encourage what it sees as viable candidates to run for office, says it has encouraged those with military service to run.

"There's no doubt that veterans have unique qualifications and experiences that give them important credibility with Democrats, independents and Republican voters alike," a committee spokesperson told ABC News last year, external.

The thing about Washington-based party elders hand-picking candidates, however, is that sometimes voters, the progressive grass-roots and other candidates don't really appreciate it.

The DCCC came out hard in February against a Democrat running for the nomination in a Houston-area race that has another vulnerable Republican incumbent, and it backfired. Progressives rallied around Laura Moser, and she raised more than $100,000 to fund her campaign in just one day and ended up qualifying for a run-off against one of the party's preferred nominees.

In the Hurd district, a similar dynamic could be playing out. Trevino, Jones's runoff opponent, is a progressive who says Bernie Sanders, the upstart Democratic candidate who challenged Clinton for the Democratic nomination, changed his life.

He is campaigning on universal healthcare, free college education and a $15 minimum wage - and says seeking "moderate Republicans" is a fool's errand.

"Right now the Republican base really thinks Democrats are vile and they're not going to vote for them," he tells me. "I say why even pander to that? Appeal to your base and excite them with ideas that are new and that bring tangible results, and then bring new voters into the fold. It's simple."

Rick Trevino says he wants to bring new voters into the fold

If there's a danger for Democrats in the 2018 midterms, a way for the wave to fizzle, it's that the party turns against itself and previously motivated voters stay home in protest. Progressives grow frustrated by what they see as more of the same from establishment Democrats, who in turn fear activists will push the party toward unelectable candidates.

Trevino, for instance, calls Jones a "pseudo-celebrity" who appeals more to Democratic donors than working-class constituents.

"Gina Ortiz Jones is just an evolution of the establishment that's cynically incorporating the language and the rhetoric and the imagery of the Bernie movement, and they're going to pass off as progressive on their terms," Trevino says. "We're ready to go and duke it out."

After the (rhetorical) fists fly, will the party come together to bring down Hurd? That's the question in Texas and across the country, where Democratic voters are facing choices about what kind candidates to back in the primaries over the coming months.

"My instinct is saying we're finally collectively coming together, and we've found some very strong candidates to say yes, it's time," says Sharon Niesen, a Jones supporter who came to her candidate's party on election night.

The Democrats better hope so.

For the people to decide

After concluding their cross-country drive last year and arriving at the US Capitol - with a few hours to spare -the two Texas congressmen took to the floor of the House of Representatives to talk about their journey.

"I got to learn a lot about the gentleman from Texas, personally I'd like to be able to call my friend," Hurd said. "He's my battle buddy now, having spent so much time in a Chevy Impala with him."

Today O'Rourke acknowledges that both of them have challenging races ahead of them. And while he could probably use a big Democratic turnout in San Antonio, he says that he's not going to get involved in Hurd's race.

"That's going to be something for the people of San Antonio and El Paso and the rest of his district to decide - whether it's Will or the eventual nominee from the Democratic runoff," he says.

The next day, I tell Hurd what his Texas colleague said and ask what he thinks of O'Rourke's race.

The election where gun control doesn't matter

"It's not rocket science," he says. "People have to make up their own minds and not do what other people tell them to do."

Politics - in Texas, the US, pretty much anywhere one's livelihood depends on the ballot box - is a cut-throat business. It's hard not to listen to Hurd and O'Rourke and understand how they could work well together in Congress; how they can sometimes disagree but never be disagreeable, in Hurd's words.

"This country would be so much better if there were more bipartisan road trips," O'Rourke tells me.

The thing is, there aren't. The road to Washington goes through the ballot box, and there's a reasonable chance that whatever electoral wave there is will wash Hurd away but not be big enough to carry O'Rourke.

In November Texas voters could tell the two "battle buddies" that Washington isn't big enough for the two of them. In fact, the two Texans could learn that there's no place in Washington for either of them.